Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) is a condition characterized by an abnormally large increase in heart rate upon sitting up or standing.

[1] POTS is a disorder of the autonomic nervous system that can lead to a variety of symptoms,[10] including lightheadedness, brain fog, blurred vision, weakness, fatigue, headaches, heart palpitations, exercise intolerance, nausea, diminished concentration, tremulousness (shaking), syncope (fainting), coldness or pain in the extremities, numbness or tingling in the extremities, chest pain, and shortness of breath.

[7] It has been shown to emerge in previously healthy patients after COVID-19,[15][16][17] or possibly in rare cases after COVID-19 vaccination, though causative evidence is limited and further study is needed.

[1] This increased heart rate should occur in the absence of orthostatic hypotension (>20 mm Hg drop in systolic blood pressure)[20] to be considered POTS.

[22] Other conditions that can cause similar symptoms, such as dehydration, orthostatic hypotension, heart problems, adrenal insufficiency, epilepsy, and Parkinson's disease, must not be present.

[34] These orthostatic symptoms include palpitations, light-headedness, chest discomfort, shortness of breath,[34] nausea, weakness or "heaviness" in the lower legs, blurred vision, and cognitive difficulties.

In some cases, patients experience a drop in pulse pressure to 0 mm Hg upon standing, rendering them practically pulseless while upright.

[37] Up to one-third of POTS patients experience fainting for many reasons, including but not limited to standing, physical exertion, or heat exposure.

This impairment, often manifesting as symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and sleep disturbances, can significantly diminish the patient's quality of life.

[34] To compensate for low blood volume, the heart increases its cardiac output by beating faster (reflex tachycardia),[56] leading to the symptoms of presyncope.

In the 30% to 60% of cases classified as hyperadrenergic POTS, norepinephrine levels are elevated on standing,[1] often due to hypovolemia or partial autonomic neuropathy.

[65] Possible mechanisms for COVID-induced POTS are hypovolemia, autoimmunity/inflammation from antibody production against autonomic nerve fibers, and direct toxic effects of COVID-19, or secondary sympathetic nervous system stimulation.

POTS also has been linked to patients with a history of autoimmune diseases,[62] long Covid,[66][67][68] irritable bowel syndrome, anemia, hyperthyroidism, fibromyalgia, diabetes, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and cancer.

[24] POTS can also co-occur in all types of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (EDS),[41][80] a hereditary connective tissue disorder marked by loose hypermobile joints prone to subluxations and dislocations, skin that exhibits moderate or greater laxity, easy bruising, and many other symptoms.

[34] These orthostatic symptoms include palpitations, light-headedness, chest discomfort, shortness of breath,[34] nausea, weakness or "heaviness" in the lower legs, blurred vision, and cognitive difficulties.

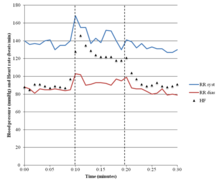

[41] Testing the cardiovascular response to prolonged head-up tilting, exercise, eating, and heat stress may help determine the best strategy for managing symptoms.

[97][99][1] People with hyperadrenergic POTS show a marked increase of blood pressure and norepinephrine levels when standing, and are more likely to have from prominent palpitations, anxiety, and tachycardia.

[7] Despite numerous therapeutic interventions proposed for the management of POTS, none have received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for this indication, and no effective treatment strategies have been identified that would have been confirmed by large clinical trials.

[103][69][70] When changing to an upright posture, finishing a meal, or concluding exercise, a sustained hand grip can briefly raise the blood pressure, possibly reducing symptoms.

[108] In these patients the selective α1-adrenergic receptor agonist midodrine may increase venous return, enhance stroke volume, and improve symptoms.

[110][111][108] Pyridostigmine, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and parasympathomimetic, has been reported to restrain heart rate and improve chronic symptoms in approximately half of people.

[114] Indirectly acting sympathomimetics, like the norepinephrine releasing agents ephedrine and pseudoephedrine and the norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors methylphenidate and bupropion, have also been used in the treatment of POTS.

Given the difficulty with current autonomic measurements in quantitatively isolating and differentiating Parasympathetic (Vagal) activity from Sympathetic activity without assumption or approximation, the current direction of research and clinical assessment is understandable: perpetuating uncertainty regarding underlying cause, prescribing beta-blockers and proper daily hydration as the only therapy, not addressing the orthostatic dysfunction as the underlying cause, and recommending acceptance and associated lifestyle changes to cope.

[citation needed] Direct measures of Parasympathetic (Vagal) activity obviates the uncertainty and lack of true relief of POTS as well as VVS.

A counter hypothesis and perhaps a simpler explanation that leads to more direct therapy and improved outcomes is again the fact that POTS and VVS may be co-morbid.

Without direct Parasympathetic (Vagal) measures, the resulting assumption is that the secondary Sympathetic over-activation (the definition of "hyperadrenergic") is actually the primary autonomic dysfunction.

Given that cases of POTS with VVS involves different portions of the nervous system (Parasympathetic and Sympathetic), and that both branches may be treated simultaneously, albeit differently, true relief of both conditions, as needed, is quite possible, and the cases of these newer hypothesized causes may be relieved with current, less expensive, and shorter-term therapy modalities.

[citation needed] A key area for further exploration of POTS management is the autonomic nervous system and its response to the orthostatic challenge.

"[146] In 2024, Taiwanese tennis player Latisha Chan revealed that she was diagnosed with POTS back in 2014 and has been receiving treatments before Summer Olympics as well.

[147] In her 2024 memoir Just Add Water, Olympic gold medalist swimmer Katie Ledecky shared that she has a mild form of POTS.