Potapy Emelianov

Potapy returned immediately to his parishioners and wrote in a letter to a fellow priest, "Do not worry that they persecute and torment us; we stand firmly upon the Rock of Peter.

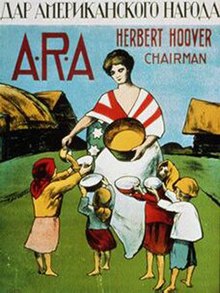

He was declared guilty of espionage, based on having gathered and shared information about local religious persecution with his superiors, who had then shared it with the western news media, and "bribing peasants to convert to Catholicism", based on his previous role in helping to distribute food and medical supplies sent by Fr Edmund A. Walsh's joint American and Papal humanitarian missions during the Russian famine of 1921.

Following nearly a decade of slave labor in the Gulag, including first felling trees above the Arctic Circle at Solovki prison camp and then digging Joseph Stalin's notorious White Sea–Baltic Canal, Potapy Emelianov died at Nadvoitsy in Soviet Karelia.

His ancestors had left the Russian Orthodox Church in the mid-17th-century, over the liturgical reforms introduced by Patriarch Nikon of Moscow and Tsar Alexis of Russia, who both enforced conformity in vain using excommunication, Siberian internal exile, torture, and even burning at the stake for heresy.

Although a monk, Brother Potapy was briefly conscripted into the Imperial Russian Army, but was released for reasons of ill-health,[1] and was sent by his Bishop to study for the Orthodox priesthood at Zhitomir.

[5] According to Deacon Vasili von Burman, "During his pastoral studies in Zhitomir, the monk Potapy became fascinated by the writings of the Holy Fathers of the Church and the proceedings of the Ecumenical Councils.

"[6] Zhitomir was the location of St Sophia's Cathedral and still remains today one of the main population centers of both Roman Catholicism and Poles in Ukraine.

In March 1917, Father Potapy was assigned to serve temporarily at the Old Ritualist Orthodox parish of ethnic Russians at Nizhnaya Bogdanovka, near Lugansk in modern Ukraine.

Potapy told his parishioners about the lives of the Roman Pontiffs, including Leo and Gregory the Great, who are also venerated as Saints in the Russian Orthodox Church.

Potapy learned that, after the 1917 February Revolution, Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky had formed an Exarchate for Russian Rite Catholics, and assigned Fr.

Potapy Emelianov arrived in Petrograd and met with the Exarch, Leonid Feodorov, whom he found living in the Rectory of St. Catherine's Roman Catholic Church on Nevsky Prospect.

Potapy returned after these efforts failed, Orthodox priests approached the occupying troops of the Imperial German Army and accused Fr.

In response, a mixed force of German soldiers and those from the Ukrainian People's Army of Pavlo Skoropadskyi's Hetmanate invaded Bogdanovka in a punitive expedition and subjected both Fr.

Mikhail Yagulov, who afterwards visited and explained to senior officers in the Imperial German Army the real reasons for the recent accusations against Fr Potapy.

[14] On 25 September 1918, Bishop Neophyte, the assistant to the Archbishop of Kharkiv, arrived in Nizhnaya Bogdanovka with a force of fifty soldiers of the Ukrainian People's Army.

Most Old Ritualist Greek Catholics of the village fled, while those who remained listened as the Bishop, with tears in his eyes, pleaded with them to return to the Russian Orthodox Church.

[17] On January 27, 1927, Father Potapy was arrested and, in a search of his rectory, GPU agents found letters from[16] Pie Eugène Neveu, A.A., formerly the parish priest of the mining town of Makiivka, Ukraine, who had been secretly consecrated as a Bishop by Michel d'Herbigny in 1926 and installed in the Church of St. Louis des Français as the secret Apostolic Administrator for Moscow Oblast.

Father Potapy's distribution of money, food, and clothing during the 1921 famine was interpreted as bribing local peasants to convert to Catholicism.

Until his arrest, Father Potapy was the last priest of the Russian Greek Catholic Church still living as a free man in the USSR.

In addition to allegedly bribing Orthodox peasants to convert to Catholicism, Father Potapy also stood accused of anti-Soviet agitation.

"[4] According to Deacon Vasili von Burman, "At that time, when the camp seemed a spiritual desert, a place of depression and even despair, the Catholic priests led a fruitful life in their closed circle...

In the context of existence on Solovki this stood out with particular clarity... On Sundays and Feast Days, services were held in the Germanovsky chapel and it was, for all its poverty, a place of celebration.

"[4] In response, however, to escalating diplomatic protests and publicity given to religious persecution in the USSR by the Holy See, the Chekist guards on Solovki cracked down on the Catholic prisoners with a vengeance.

[23] According to Irina Osipova, "On Anzer Island the Catholic Clergy were housed in separate barracks and even at work were permitted no contact with other convicts.

Potapy, aiming to relieve, as far as possible, the plight of his poor sick brother, secured his own transfer to the same ward and cared for the patient like a mother... Fr.

Potapy and his fellow Catholic priests then successfully overcame seemingly impossible obstacles to build a coffin and give Fr.

The letter read, "We, Catholic priests and almost all elderly or sick, are often forced to undertake the heaviest labor, as, for example, excavating trenches to build foundations, hauling great rocks, digging at the frozen ground in winter... We sometimes have to be outside on duty for 16 hours a day in winter, without a break and with no shelter... After heavy work we absolutely require a lengthy rest period but in our accommodation the space per man is at times reduced to less than one sixteenth of the volume of air a human being needs to survive.

"[30] In the summer of 1932, Father Potapy was one of 23 priests arrested as part of the GPU's investigation and prosecution of, "The anti-Soviet counterrevolutionary organization of Catholic and Uniate Clergy on Anzer Island.

Potapy Emelianov, who had been one of the slave laborers who remained to run the canal after its completion, was finally released from the Gulag and sentenced to internal exile.

"[35] Pavel Parfentiev, the former Postulator for his Sainthood cause, gives Father Potapy's place of death instead as the still extant railroad station at Nadvoitsy, but adds that, if he was buried, the location of his grave remains unknown.