Gulag

The abbreviation GULAG (ГУЛАГ) stands for "Гла́вное Управле́ние исправи́тельно-трудовы́х ЛАГере́й" (Main Directorate of Correctional Labour Camps), but the full official name of the agency changed several times.

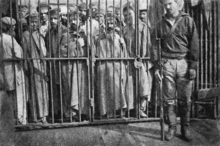

The camps housed both ordinary criminals and political prisoners, a large number of whom were convicted by simplified procedures, such as NKVD troikas or other instruments of extrajudicial punishment.

It was renamed several times, e.g., to Main Directorate of Correctional Labor Colonies (Главное управление исправительно-трудовых колоний (ГУИТК)), which names can be seen in the documents describing the subordination of various camps.

[34][35] Although the term Gulag was originally used in reference to a government agency, in English and many other languages, the acronym acquired the qualities of a common noun, denoting the Soviet system of prison-based, unfree labor.

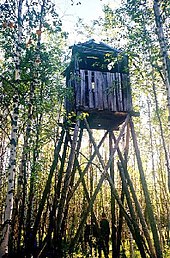

[41] Convicts who were serving labor sentences and exiles were sent to the underpopulated areas of Siberia and the Russian Far East – regions that lacked towns or food sources as well as organized transportation systems.

[45] These early camps of the GULAG system were introduced in order to isolate and eliminate class-alien, socially dangerous, disruptive, suspicious, and other disloyal elements, whose deeds and thoughts were not contributing to the strengthening of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

[48] Various categories of prisoners were defined: petty criminals, POWs of the Russian Civil War, officials accused of corruption, sabotage and embezzlement, political enemies, dissidents and other people deemed dangerous for the state.

Hence it is followed by one more important reason for the constancy of the repressive policy, namely, the state's interest in unremitting rates of receiving a cheap labor force that was forcibly used, mainly in the extreme conditions of the east and north.

All of the "special settlers", as the Soviet government referred to them, lived on starvation level rations, and as a result, many people starved to death in the camps, and anyone who was healthy enough to escape tried to do just that.

The OGPU also attempted to raise the living conditions in these camps in order to discourage people from actively trying to escape from them, and Kulaks were told that they would regain their rights in five years.

[citation needed] These included the exploitation of natural resources and the colonization of remote areas, as well as the realisation of enormous infrastructural facilities and industrial construction projects.

Hundreds of thousands of persons were arrested and sentenced to long prison terms on the grounds of one of the multiple passages of the notorious Article 58 of the Criminal Codes of the Union republics, which defined punishment for various forms of "counterrevolutionary activities".

[43] Information regarding the imprisonment trends and consequences for the intelligentsia derive from the extrapolations of Viktor Zemskov from a collection of prison camp population movements data.

[65][66] After the German invasion of Poland that marked the start of World War II in Europe, the Soviet Union invaded and annexed eastern parts of the Second Polish Republic.

[77] To improve the situation, laws were implemented in mid-1940 that allowed giving short camp sentences (4 months or a year) to those convicted of petty theft, hooliganism, or labor-discipline infractions.

The release of political prisoners started in 1954 and became widespread, and also coupled with mass rehabilitations, after Nikita Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalinism in his Secret Speech at the 20th Congress of the CPSU in February 1956.

"[104] Certificates of death in the Gulag system for the period from 1930 to 1956[105] Living and working conditions in the camps varied significantly across time and place, depending, among other things, on the impact of broader events (World War II, countrywide famines and shortages, waves of terror, sudden influx or release of large numbers of prisoners) and the type of crime committed.

[113] In general, the central administrative bodies showed a discernible interest in maintaining the labor force of prisoners in a condition allowing the fulfilment of construction and production plans handed down from above.

[117] On 7 August 1932, a new decree drafted by Stalin (Law of Spikelets) specified a minimum sentence of ten years or execution for theft from collective farms or of cooperative property.

It would be virtually impossible to reflect the entire mass of Gulag facilities on a map that would also account for the various times of their existence.Since many of these existed only for short periods, the number of camp administrations at any given point was lower.

[129]: 444–5 Arendt argues that together with the systematized, arbitrary cruelty inside the camps, this served the purpose of total domination by eliminating the idea that the arrestees had any political or legal rights.

Amid glasnost and democratization in the late 1980s, Viktor Zemskov and other Russian researchers managed to gain access to the documents and published the highly classified statistical data collected by the OGPU-NKVD-MGB-MVD and related to the number of the Gulag prisoners, special settlers, etc.

On the other hand, overstatement of data of the number of prisoners also did not comply with departmental interests, because it was fraught with the same (i.e., impossible) increase in production tasks set by planning bodies.

Thus, Sergei Maksudov alleged that although literary sources, for example the books of Lev Razgon or Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, did not envisage the total number of the camps very well and markedly exaggerated their size.

He added that without distinguishing the degree of accuracy and reliability of certain figures, without making a critical analysis of sources, without comparing new data with already known information, Zemskov absolutizes the published materials by presenting them as the ultimate truth.

Zemskov added that when he tried not to overuse the juxtaposition of new information with "old" one, it was only because of a sense of delicacy, not to once again psychologically traumatize the researchers whose works used incorrect figures, as it turned out after the publication of the statistics by the OGPU-NKVD-MGB-MVD.

[145] During the decades before the dissolution of the USSR, the debates about the population size of GULAG failed to arrive at generally accepted figures; wide-ranging estimates have been offered,[146] and the bias toward higher or lower side was sometimes ascribed to political views of the particular author.

The glasnost political reforms in the late 1980s and the subsequent dissolution of the USSR, led to the release of a large amount of formerly classified archival documents[157] including new demographic and NKVD data.

[4] Preliminary analysis of the GULAG camps and colonies statistics (see the chart on the right) demonstrated that the population reached the maximum before the World War II, then dropped sharply, partially due to massive releases, partially due to wartime high mortality, and then was gradually increasing until the end of Stalin era, reaching the global maximum in 1953, when the combined population of GULAG camps and labor colonies amounted to 2,625,000.

[165] According to a 2024 study, areas near gulag camps that held a larger share of educated elites among its prisoner population have subsequently been characterized by greater economic growth.