Potlatch

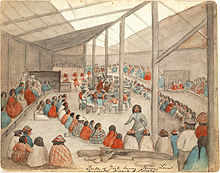

A potlatch is a gift-giving feast practiced by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and the United States,[1] among whom it is traditionally the primary governmental institution, legislative body, and economic system.

[clarification needed][2] This includes the Heiltsuk, Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit,[3] Makah, Tsimshian,[4] Nuu-chah-nulth,[5] Kwakwaka'wakw,[2] and Coast Salish cultures.

Typically the potlatch was practiced more in the winter seasons as historically the warmer months were for procuring wealth for the family, clan, or village, then coming home and sharing that with neighbors and friends.

If a member of a nation had suffered an injury or indignity, hosting a potlatch could help to heal their tarnished reputation (or "cover his shame", as anthropologist H. G. Barnett worded it).

[12]: 198 Secondly, there were a number of titles that would be passed between numayma, usually to in-laws, which included feast names that gave one a role in the Winter Ceremonial.

[12]: 201 Any one individual might have several "seats" which allowed them to sit, in rank order, according to their title, as the host displayed and distributed wealth and made speeches.

It is the distribution of large numbers of Hudson Bay blankets, and the destruction of valued coppers that first drew government attention (and censure) to the potlatch.

[14] Dorothy Johansen describes the dynamic: "In the potlatch, the host in effect challenged a guest chieftain to exceed him in his 'power' to give away or to destroy goods.

If the guest did not return 100 percent on the gifts received and destroy even more wealth in a bigger and better bonfire, he and his people lost face and so his 'power' was diminished.

"[15] Hierarchical relations within and between clans, villages, and nations, were observed and reinforced through the distribution or sometimes destruction of wealth, dance performances, and other ceremonies.

Once the child reached about 12 years of age, they were expected to hold a potlatch of their own by giving out small gifts that they had collected to their family and people, at which point they would be able to receive their third name.

Many of these dances are also sacred ceremonies of secret societies like the hamatsa, or display of family origin from supernatural creatures such as the dzunukwa.

[17]Among the various First Nations groups which inhabited the region along the coast, a variety of differences existed in regards to practises relating to the potlatch ceremony.

It is important to keep this variation in mind as most of our detailed knowledge of the potlatch was acquired from the Kwakwaka'wakw around Fort Rupert on Vancouver Island in the period 1849 to 1925, a period of great social transition in which many aspects of the potlatch became exacerbated in reaction to efforts by the Canadian government to culturally assimilate First Nations communities into the dominant white culture.

[19] This resulted in massive inflation in gifting made possible by the introduction of mass-produced trade goods in the late 18th and earlier 19th centuries.

To some extent, this was at the urging of missionaries and government agents who considered it "a worse than useless custom" that was seen as wasteful, unproductive, and contrary to 'civilized values' of accumulation.

[26]In 1888, the anthropologist Franz Boas described the potlatch ban as a failure: The second reason for the discontent among the Indians is a law that was passed, some time ago, forbidding the celebrations of festivals.

These feasts are so closely connected with the religious ideas of the natives, and regulate their mode of life to such an extent, that the Christian tribes near Victoria have not given them up.

Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to change the offence from criminal to summary, which meant "the agents, as justice of the peace, could try a case, convict, and sentence".

Despite these differences, Kan stated that he believed that many of the essential elements and spirit of the traditional potlatch were still present in the contemporary Tlingit ceremonies.

[32] These societies' economies are marked by the competitive exchange of gifts, in which gift-givers seek to out-give their competitors so as to capture important political, kinship and religious roles.