Potosí

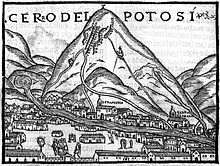

The Cerro Rico is the reason for Potosí's historical importance since it was the major supply of silver for the Spanish Empire until Guanajuato in Mexico surpassed it in the 18th century.

It features a rare cold highland climate, and is marked by its long dry period, and short but strong wet season.

While famous for its dominance as a mining center in early Spanish colonial history, Potosí still sits at one of the largest silver deposit systems in the world.

Located in the Bolivian Tin Belt, Cerro Rico de Potosí is the world's largest silver deposit and has been mined since the sixteenth century, producing up to 60,000 tonnes by 1996.

The conical hill has a reddish-brown gossan cap of iron-oxides and quartz, with grayish-blue altered dacite and many mine dumps below.

During the explosive process, the Venus breccia formed when the ascending dacite magma reacted with groundwater to produce a phreatic eruption.

Silver production was revived by the introduction of the patio process, invented by Spanish merchant Bartolomé de Medina in 1554.

Potosí was a mythical land of riches, it is mentioned in Miguel de Cervantes' famous novel, Don Quixote (second part, chap.

Although in mountainous terrain, the core of Potosí was laid out in the standard Spanish grid pattern, where by 1610 some 3,000 Spaniards and 35,000 creoles, mostly male, were resident.

Large churches, lavishly decorated inside, were built, and friars from the Dominican, Franciscans, Augustinians, Mercederians, and Jesuits were present, but no convent for women.

While more skilled laborers extracted the ore, mitayos were tasked with carrying it back to the surface in baskets, leather bags, or cloth sacks.

[22][23] These loads often weighed between 100 and 300 lbs, and the workers had to carry them up rickety ladders in steep, narrow shafts lit only by a candle tied to their foreheads.

Illness was another danger: at such a high altitude, pneumonia was always a concern, especially given the extreme and rapid changes of temperature experienced by workers climbing from the heat of the deep shafts to the freezing elements of the surface at 16,000 feet, and mercury poisoning took the lives of many involved in the refining process.

[25] This only increased the burden on the remaining natives, and at some point in the 1600s, up to half of the eligible male population might find themselves working at Potosí.

Mine and mill owners notoriously ignored official regulations on provisions and especially withheld the money the Indians should receive as recompensation for their travel.

[27] Former mitayos living in Potosí were not only exempt from the draft, but usually earned considerably more due to the valuable skills they had gained in permanent services.

According to his research, though as few as 4500 mitayos were actively laboring in the mines at any given time, this was due to the mita ordinaria system, in which the up to 13,500 men conscripted per year were divided into three parts, each working one out of every three weeks.

Small-scale female vendors dominated street markets and stalls, selling food, coca leaves, and chicha (maize beer).

They gathered in a confederation opposed to another one, the Vicuñas, a melting pot of natives and non-Basque Spanish and Portuguese colonists, fighting for control over ore extraction from the mines and its management.

Both factions reached a settlement sealed with a wedding between the son and daughter of the leaders in either side, the Basque Francisco Oyanume and the Vicuña general Castillo.

One of the most famous Basque residents in Potosí (1617–19) was Catalina de Erauso, a nun who escaped her convent and dressed as a man, becoming a driver of llamas and a soldier.

Major leadership mistakes came when the First Auxiliary Army arrived from Buenos Aires (under the command of Juan José Castelli), which led to an increased sense that Potosí required its own independent government.

Before leaving there, he saw Potosí, and admiring its beauty and grandeur, he said (speaking to those of his Court): "This doubtless must have much silver in its heart"; whereby he subsequently ordered his vassals to go to Ccolque Porco ... and work the mines and remove from them all the rich metal.

The city is served by Aeropuerto Capitán Nicolas Rojas, with commercial airline flights by Boliviana de Aviación, Bolivia's flag air carrier.