Divergence

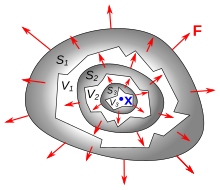

It is a local measure of its "outgoingness" – the extent to which there are more of the field vectors exiting from an infinitesimal region of space than entering it.

A point at which the flux is outgoing has positive divergence, and is often called a "source" of the field.

A point at which the flux is directed inward has negative divergence, and is often called a "sink" of the field.

A vector field with zero divergence everywhere is called solenoidal – in which case any closed surface has no net flux across it.

In three-dimensional Cartesian coordinates, the divergence of a continuously differentiable vector field

Although expressed in terms of coordinates, the result is invariant under rotations, as the physical interpretation suggests.

The common notation for the divergence ∇ · F is a convenient mnemonic, where the dot denotes an operation reminiscent of the dot product: take the components of the ∇ operator (see del), apply them to the corresponding components of F, and sum the results.

the divergence in cartesian coordinate system is a first-order tensor field[3] and can be defined in two ways:[4]

Using Einstein notation we can consider the divergence in general coordinates, which we write as x1, …, xi, …, xn, where n is the number of dimensions of the domain.

The Einstein notation implies summation over i, since it appears as both an upper and lower index.

The volume coefficient ρ is a function of position which depends on the coordinate system.

The determinant appears because it provides the appropriate invariant definition of the volume, given a set of vectors.

Since the determinant is a scalar quantity which doesn't depend on the indices, these can be suppressed, writing

The absolute value is taken in order to handle the general case where the determinant might be negative, such as in pseudo-Riemannian spaces.

The reason for the square-root is a bit subtle: it effectively avoids double-counting as one goes from curved to Cartesian coordinates, and back.

The volume (the determinant) can also be understood as the Jacobian of the transformation from Cartesian to curvilinear coordinates, which for n = 3 gives

Some conventions expect all local basis elements to be normalized to unit length, as was done in the previous sections.

Most importantly, the divergence is a linear operator, i.e., for all vector fields F and G and all real numbers a and b.

The degree of failure of the truth of the statement, measured by the homology of the chain complex serves as a nice quantification of the complicatedness of the underlying region U.

It is a special case of the more general Helmholtz decomposition, which works in dimensions greater than three as well.

For any n, the divergence is a linear operator, and it satisfies the "product rule" for any scalar-valued function φ.

Define the current two-form as It measures the amount of "stuff" flowing through a surface per unit time in a "stuff fluid" of density ρ = 1 dx ∧ dy ∧ dz moving with local velocity F. Its exterior derivative dj is then given by where

Thus, the divergence of the vector field F can be expressed as: Here the superscript ♭ is one of the two musical isomorphisms, and ⋆ is the Hodge star operator.

Working with the current two-form and the exterior derivative is usually easier than working with the vector field and divergence, because unlike the divergence, the exterior derivative commutes with a change of (curvilinear) coordinate system.

The square-root of the (absolute value of the determinant of the) metric appears because the divergence must be written with the correct conception of the volume.

In curvilinear coordinates, the basis vectors are no longer orthonormal; the determinant encodes the correct idea of volume in this case.

The square-root appears in the denominator, because the derivative transforms in the opposite way (contravariantly) to the vector (which is covariant).

This idea of getting to a "flat coordinate system" where local computations can be done in a conventional way is called a vielbein.

In Einstein notation, the divergence of a contravariant vector Fμ is given by where ∇μ denotes the covariant derivative.

In this general setting, the correct formulation of the divergence is to recognize that it is a codifferential; the appropriate properties follow from there.