Prandtl–Meyer expansion fan

The fan consists of an infinite number of Mach waves, diverging from a sharp corner.

When a flow turns around a smooth and circular corner, these waves can be extended backwards to meet at a point.

Each wave in the expansion fan turns the flow gradually (in small steps).

It is physically impossible for the flow to turn through a single "shock" wave because this would violate the second law of thermodynamics.

[1] Across the expansion fan, the flow accelerates (velocity increases) and the Mach number increases, while the static pressure, temperature and density decrease.

The theory was described by Theodor Meyer on his thesis dissertation in 1908, along with his advisor Ludwig Prandtl, who had already discussed the problem a year before.

with respect to the flow direction, and the last Mach line is at an angle

is the heat capacity ratio of the gas (1.4 for air): The Mach number after the turn (

This function determines the angle through which a sonic flow (M = 1) must turn to reach a particular Mach number (M).

The velocity field in the expansion fan, expressed in polar coordinates

However, as the flow turns, its static pressure decreases (as described earlier).

If there is not enough pressure to start with, the flow won't be able to complete the turn and will not be parallel to the wall.

This shows up as the maximum angle through which a flow can turn.

), the greater the maximum angle through which the flow can turn.

The streamline which separates the final flow direction and the wall is known as a slipstream (shown as the dashed line in the figure).

Beyond the slipstream the flow is stagnant (which automatically satisfies the velocity boundary condition at the wall).

In case of real flow, a shear layer is observed instead of a slipstream, because of the additional no-slip boundary condition.

Impossibility of expanding a flow through a single "shock" wave: Consider the scenario shown in the adjacent figure.

As a supersonic flow turns, the normal component of the velocity increases (

is the component of flow velocity normal to the "shock".

The suffix "1" and "2" refer to the initial and final conditions respectively.

Since this is not possible, it means that it is impossible to turn a flow through a single shock wave.

Mach lines are a concept usually encountered in 2-D supersonic flows (i.e.

In case of 3-D flow field, these lines form a surface known as Mach cone, with Mach angle as the half angle of the cone.

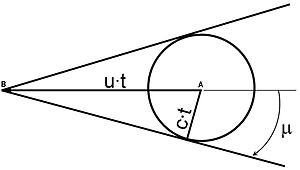

To understand the concept better, consider the case sketched in the figure.

We know that when an object moves in a flow, it causes pressure disturbances (which travel at the speed of sound, also known as Mach waves).

The figure shows an object moving from point A to B along the line AB at supersonic speeds (

There are infinite such circles with their centre on the line AB, each representing the location of the disturbances due to the motion of the object.

Note: These concepts have a physical meaning only for supersonic flows (

In case of subsonic flows, the disturbances will travel faster than the source and the argument of the