Pre-Cabraline history of Brazil

[1] A further aggravating factor is that much remains to be done at various levels of research - language records and comparisons, analysis of excavated materials, the relationship between antiquity sites and others from the colonial period.

[2] Lund lived much of his life in Brazil, and was responsible for studying several reminiscences of ancient plants in the caves of the Lagoa Santa region (Minas Gerais), where he settled between 1834 and 1880.

[2] Middens, shell mounds, and other debris accumulated by human action were archeological remains responsible for stirring scientific debate in the 19th century.

Hermann Von Ihering, however, the director of the Ipiranga Museum, first opposed this view, stating that the shell remains would have been formed by natural, intertropical phenomena.

A. Padberg-Drenkpohl, hired after World War I by the National Museum, was another important figure in the history of Brazilian archaeology, who excavated at Lagoa Santa between 1926 and 1929.

[2] Accompanying this advance in the question of preservation of Brazilian memory, excavations were carried out at the mouth of the Amazon river by Clifford Evans and Betty J. Meggers between 1949 and 1950, discovering important ceramic artifacts, and in São Paulo and Paraná between 1954 and 1956 by Joseph Emperaire and Annette Laming - where the first Carbon-14 datings were made.

[5] The occupation of American territory is a topic that has generated substantial controversy, especially as many archaeologists are still reluctant to accept that humans could have arrived in the Americas by other routes than the Bering land bridge.

[1] Also at this same site, archaeologists were able to find human artifacts dating back to more than 48,000 BP[15] The discoveries in Brazil led to polemics about the traditional view of the occupation of the Americas[16] and archeologists started to defend other theories about the great migrations, among them, that humans arrived in the Americas between 150,000 and 100,000 years ago, arriving by Malay-Polynesian (from Southeast Asia) or Australian (from the South Pacific) currents, while other authors still think of a migration current originating in Africa.

Found by French archaeologist Annette Laming-Emperaire in the 1970s at the archaeological site of Lapa Vermelha, in the municipality of Lagoa Santa (Minas Gerais), the fossil of this prehistoric woman contributes to reigniting an old debate about the origins of humans in the Americas.

[19] According to paleoanthropologist Walter Neves, responsible for naming the fossil, the morphology of Luzia's skull would bring her closer to the current aborigins of Australia and natives of Africa.

[19] Neves ventured the hypothesis that the occupation of the Americas was older than previously imagined, although not going back very far in time (about 14,000 years before the present), and that it was carried out by peoples from distinct regions, such as Oceania and Africa.

In the northeast, several archeological sites indicate the development of chipped stone, containing slugs (a slug-shaped lithic artifact used to scrape wooden supports), splinters, awls, and stoves for roasting meat.

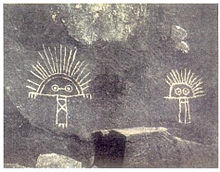

According to some archaeologists, the themes of violence in ancient rock art would be linked to the technical development achieved in subsequent years, responsible for promoting more efficient hunting strategies.

[30] In Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, artifacts (knives, scrapers, arrowheads) from 8,500 to 6,500 years ago have been located, established as the "Vinitu tradition".

The demographic increase of Amazonian populations in late Prehistoric times, combined with other factors, gave rise to major transformations among the indigenous societies of the Amazon.

"[42] These societies became increasingly hierarchical containing nobles, "commoners" and captive servants,[42] with a centralized leadership in the figure of the cacique, and adopted bellicose and expansionist attitudes.

[44][1] According to researcher Anna Roosevelt, "The development of intensive agriculture in prehistoric times seems to have been correlated to the rapid expansion of the populations of complex societies.

Suggestively, the displacements and depopulation of the historical period caused these economies to return to patterns of less intensive root cultivation and animal capture (...).

[50] One of the distinguished features of the complex societies of Marajó Island is the "tesos", large artificial embankments built to place dwellings, probably to avoid flooding.

[51] In October 2009, a group of geologists claimed that the tesos could be essentially natural structures, by processes similar to fluvial mound formation elsewhere, with evidence of human activity only in more superficial layers.

[53] Archaeologists responsible for the excavation and anthropogenic hypothesis have questioned the team's methodology, pointing to sample sizes and evidence in the study that could be interpreted as signifying human structures.

[59] The archaeological site of Pedra Furada,[60] located in São Raimundo Nonato, in the Serra da Capivara National Park, Piauí, was discovered in the 1960s.

Guidon's thesis goes much further - about 100,000 years - and assumes that humans did not arrive in America from Asia by land (via the Bering Strait as is believed until today), but by sea, using boats.

The conceptions of the current Indians living in the northeast region of the country, like the Kiriri, although much modified, may still be a useful element to decipher such representations with a conjectural strategy.

[63][64][65] In 1974, at Lapa Vermelha IV, during the excavation of Annette Laming-Emperaire's team, a human skeleton dated 11,500 years BP, the oldest in the Americas, was discovered, later nicknamed Luzia.

She cast doubt on the Clovis Theory since she is a woman with characteristics very distinct from today's indigenous people (who are closer to the epigenetic Mongoloid group).

Luzia was investigated by bioanthropologists and archaeologists Walter Alves Neves, André Prous, Joseph F. Powell, Erik G. Ozolins, and Max Blum.

[69][70] The Tupi-Guaraní expansion happened between 3,000 and 2,000 years ago, shortly after this group differentiated from others in the region between the Xingu and Madeira rivers, forming new language subgroups, such as the Cocama, Omágua, Guaiaqui, and Xirinó.

"[75] The names of some of the main groups that inhabited Brazil on the eve of the European arrival are (among them some of non-Tupi origin): The Potiguara, Tremembé, Tabajara, Caeté, Tupiniquim, the Tupinambá, Aimoré, Goitacá, Tamoio, Carijó and Temiminó.

[84][85] Of these agreements signed at a distance from the assigned land, the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) is the most important, for defining the portions of the globe that would belong to Portugal during the period in which Brazil was a Portuguese colony.