History of Iran

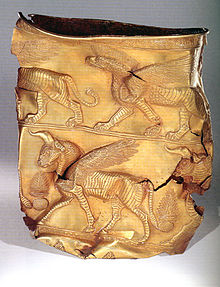

[1] The western part of the Iranian plateau participated in the traditional ancient Near East with Elam (in Ilam and Khuzestan), Kassites (in Kuhdesht), Gutians (in Luristan) and later with other peoples such as the Urartians (in Oshnavieh and Sardasht) in the southwest of Lake Urmia[2][3][4][5] and Mannaeans (in Piranshahr, Saqqez and Bukan) in the Kurdish area.

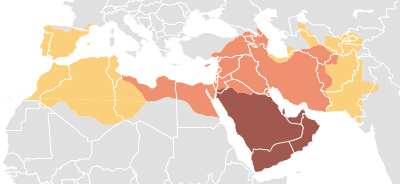

The Muslim conquest of Persia (632–654) ended the Sasanian Empire and marked a turning point in Iranian history, leading to the Islamization of Iran from the eighth to tenth centuries and the decline of Zoroastrianism.

[26] Evidence for Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic periods are known mainly from the Zagros Mountains in the caves of Kermanshah and Khorramabad and a few number of sites in Piranshahr, Alborz and Central Iran.

In 612 BC, Cyaxares, Deioces' grandson, and the Babylonian king Nabopolassar invaded Assyria and laid siege to and eventually destroyed Nineveh, the Assyrian capital, which led to the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

At a crucial moment in the war, about half of mainland Greece was overrun by the Persians, including all territories to the north of the Isthmus of Corinth,[62][63] however, this was also turned out in a Greek victory, following the battles of Plataea and Salamis, by which Persia lost its footholds in Europe, and eventually withdrew from it.

During this time, the Sassanian and Romano-Byzantine armies clashed for influence in Anatolia, the western Caucasus (mainly Lazica and the Kingdom of Iberia; modern-day Georgia and Abkhazia), Mesopotamia, Armenia and the Levant.

As Bernard Lewis has commented: "These events have been variously seen in Iran: by some as a blessing, the advent of the true faith, the end of the age of ignorance and heathenism; by others as a humiliating national defeat, the conquest and subjugation of the country by foreign invaders.

The most prominent ruler of the Dabuyids, known as Farrukhan the Great (r. 712–728), managed to hold his domains during his long struggle against the Arab general Yazid ibn al-Muhallab, who was defeated by a combined Dailamite-Dabuyid army, and was forced to retreat from Tabaristan.

[81] The Ghaznavid empire grew by taking all of the Samanid territories south of the Amu Darya in the last decade of the 10th century, and eventually occupied parts of Eastern Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and north-west India.

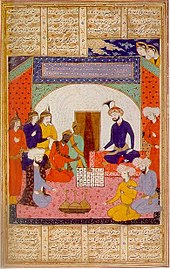

Under Tughril Beg's successor, Malik Shah (1072–1092), Iran enjoyed a cultural and scientific renaissance, largely attributed to his brilliant Iranian vizier, Nizam al Mulk.

There were however some exceptions to this general domination which emerged in the form of the Zaydīs of Tabaristan (see Alid dynasties of northern Iran), the Buyids, the Kakuyids, the rule of Sultan Muhammad Khudabandah (r. Shawwal 703-Shawwal 716/1304–1316) and the Sarbedaran.

The Kara Koyunlu expanded their conquest to Baghdad, however, internal fighting, defeats by the Timurids, rebellions by the Armenians in response to their persecution,[121] and failed struggles with the Ag Qoyunlu led to their eventual demise.

[122] Aq Qoyunlu were Turkmen[123][124] under the leadership of the Bayandur tribe,[125] tribal federation of Sunni Muslims who ruled over most of Iran and large parts of surrounding areas from 1378 to 1501 CE.

The Safavids ruled from 1501 to 1722 (experiencing a brief restoration from 1729 to 1736) and at their height, they controlled all of modern Iran, Azerbaijan and Armenia, most of Georgia, the North Caucasus, Iraq, Kuwait and Afghanistan, as well as parts of Turkey, Syria, Pakistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Afterwards he went on a campaign of conquest, and following the capture of Tabriz in July 1501, he enthroned himself as the Shāh of Iran,[130]: 324 [131][132] minted coins in this name, and proclaimed Shi'ism the official religion of his domain.

[18] Although initially the masters of Azerbaijan and southern Dagestan only, the Safavids had, in fact, won the struggle for power in Iran which had been going on for nearly a century between various dynasties and political forces following the fragmentation of the Kara Koyunlu and the Aq Qoyunlu.

As Encyclopædia Iranica states, for Tahmasp, the problem circled around the military tribal elite of the empire, the Qizilbash, who believed that physical proximity to and control of a member of the immediate Safavid family guaranteed spiritual advantages, political fortune, and material advancement.

Shah Abbas I and his successors would significantly expand this policy and plan initiated by Tahmasp, deporting during his reign alone around some 200,000 Georgians, 300,000 Armenians and 100,000–150,000 Circassians to Iran, completing the foundation of a new layer in Iranian society.

In 1722, Peter the Great of neighbouring Imperial Russia launched the Russo-Persian War (1722–1723), capturing many of Iran's Caucasian territories, including Derbent, Shaki, Baku, but also Gilan, Mazandaran and Astrabad.

Control of Persia remained contested between the United Kingdom and Russia, in what became known as The Great Game, and codified in the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, which divided Iran into spheres of influence, regardless of her national sovereignty.

Tensions boiled over in 1935, when bazaaris and villagers rose up in rebellion at the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad to protest against plans for the hijab ban, chanting slogans such as 'The Shah is a new Yezid.'

Pahlavi increased his political power by convening the Iran Constituent Assembly, 1949, which finally formed the Senate of Iran—a legislative upper house allowed for in the 1906 constitution but never brought into being.

The consolidation lasted until 1982–3,[201][202] as Iran coped with the damage to its economy, military, and apparatus of government, and protests and uprisings by secularists, leftists, and more traditional Muslims—formerly ally revolutionaries but now rivals—were effectively suppressed.

Following the events of the revolution, Marxist guerrillas and federalist parties revolted in regions comprising Khuzistan, Kurdistan and Gonbad-e Qabus, resulting in severe fighting between rebels and revolutionary forces.

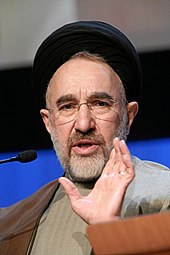

"[219] Ali-Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani succeeded Khamenei as president on 3 August 1989, as a pragmatic conservative who served two four-year terms and focused his efforts on rebuilding the country's economy and infrastructure damaged by war, though hampered by low oil prices.

Rafsanjani sought to restore confidence in the government among the general population by privatizing the companies that had been nationalized in the first few years of the Islamic Republic, as well as by bringing in qualified technocrats to manage the economy.

However, these new amendments did not curtail the powers of the Supreme Leader of Iran in any way; this position still contained the ultimate authority over the armed forces, the making of war and peace, the final say in foreign policy, and the right to intervene in the legislative process whenever he deemed it necessary.

[227] At least one commentator (former U.S. Defense Secretary William S. Cohen) has stated that as of 2009 Iran's growing power has eclipsed anti-Zionism as the major foreign policy issue in the Middle East.

[237] On 3 January 2020, the United States military executed a drone strike at Baghdad Airport, killing Qasem Soleimani, the leader of the Quds Force, an elite branch of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

[240][241][242] On 1 April 2024, Israel's air strike on an Iranian consulate building in the Syrian capital Damascus killed an important senior commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), Brig Gen Mohammad Reza Zahedi.