Prehistory of the Netherlands

Inhabited by humans for at least 37,000 years, the landscape underwent significant transformations, from the last ice age's tundra climate to the emergence of various Paleolithic groups.

The arrival of agriculture around 5000–4000 BC marked the beginning of the Linear Pottery culture, which gradually transformed prehistoric communities.

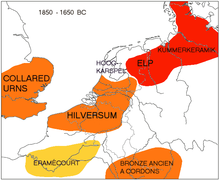

The Iron Age, on the other hand, brought about the spread of Germanic and Celtic influences in the region, exemplified by the Elp and Hilversum cultures.

The pre-Roman period was characterized by a complex interplay of different cultures and ethnicities, including the emergence of early Frisians, Saxons and Salian Franks.

The area that is now the Netherlands was inhabited by early humans at least 37,000 years ago, as attested by flint tools discovered in Woerden in 2010.

At the end of the Ice Age, the nomadic late Upper Palaeolithic Hamburg culture (13,000–10,000 BC) hunted reindeer in the area, using spears.

Dutch archaeologist Leendert Louwe Kooijmans wrote, "It is becoming increasingly clear that the agricultural transformation of prehistoric communities was a purely indigenous process that took place very gradually.

"[6] This transformation took place as early as 4300 BC–4000 BC[8] and featured the introduction of grains in small quantities into a traditional broad-spectrum economy.

The subsequent phase was that of cremating the dead and placing their ashes in urns which were then buried in fields, following the customs of the Urnfield culture (1200–800 BC).

The Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures were not indigenous to the Netherlands but were pan-European in nature, extending across much of northern and central Europe.

The King's grave of Oss (700 BC) was found in a burial mound, the largest of its kind in Western Europe and containing an iron sword with an inlay of gold and coral.

In Oss, a grave dating from around 500 BC was found in a burial mound 52 metres wide (and thus the largest of its kind in western Europe).

Dubbed the "king's grave" (Vorstengraf (Oss)), it contained extraordinary objects, including an iron sword with an inlay of gold and coral.

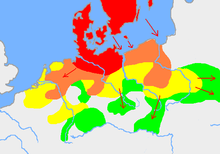

The contemporary southern and western migration of Germanic groups and the northern expansion of the Hallstatt culture drew these peoples into each other's sphere of influence.

The Germanic tribes originally inhabited southern Scandinavia, Jutland peninsula and northern Germany,[19] but subsequent Iron Age cultures of the same region, like Wessenstedt (800–600 BC) and Jastorf, also belonged to this grouping.

Archaeological evidence suggests around 750 BC a relatively uniform Germanic people came to the Netherlands from the Vistula and southern Scandinavia.

[19] In the west, the newcomers settled the coastal floodplains for the first time, since in adjacent higher grounds the population had increased and the soil had become exhausted.

[24] By the later La Tène period (c. 450 BC up to the Roman conquest), this Celtic culture had, whether by diffusion or migration, expanded over a wide range, including into the southern area of the Netherlands.

According to archaeologists these finds confirmed that at least the Meuse (Dutch: Maas) river valley in the Netherlands was within the influence of the La Tène culture.

Dutch archaeologists even speculate that Zutphen (which lies in the centre of the country) was a Celtic area before the Romans arrived, not a Germanic one at all.

[citation needed] But according to Belgian linguist Luc van Durme, toponymic evidence of a former Celtic presence in the Low Countries is near to utterly absent.

[21] Some scholars (De Laet, Gysseling, Hachmann, Kossack & Kuhn) have speculated that a separate ethnic identity, neither Germanic nor Celtic, survived in the Netherlands until the Roman period.

[30][31] Their view is that this culture, which had its own language, was being absorbed by the Celts to the south and the Germanic peoples from the east as late as the immediate pre-Roman period.