Presidency of William Howard Taft

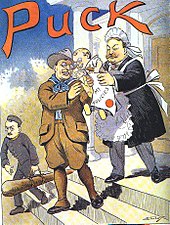

The protégé and chosen successor of President Theodore Roosevelt, he took office after easily defeating Democrat William Jennings Bryan in the 1908 presidential election.

Taft hoped his running mate would be a Midwestern progressive such as Iowa Senator Jonathan Dolliver, but instead the convention named Congressman James S. Sherman of New York, a conservative.

[5][6] Taft began the campaign on the wrong foot, fueling the arguments of those who said he was not his own man by traveling to Roosevelt's home at Sagamore Hill for advice on his acceptance speech, saying that he needed "the president's judgment and criticism".

He attributed blame for the recent recession, the Panic of 1907, to stock speculation and other abuses, and felt some reform of the currency (the U.S. was on the gold standard) was needed to allow flexibility in the government's response to poor economic times.

On November 17, 1908, President-elect Taft spoke in agreement with the stance expressed by Secretary of War Luke Edward Wright supporting free trade of sugar and tobacco with the Philippines.

[citation needed] James S. Sherman had been added to the 1908 Republican ticket as a means to appease the conservative wing of the GOP, which viewed Taft as a progressive.

The conservative Van Devanter was the lone Taft appointee to serve past 1922, and he formed part of the Four Horsemen bloc that opposed Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal.

Aldrich's amendments outraged progressives such as Wisconsin's Robert M. La Follette, who strongly opposed the high rates of the Payne-Aldrich tariff bill.

The amendment would overturn the Supreme Court's ruling in the 1895 case of Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co., and allow Congress to implement an income tax.

These conservative forces were initially confident that over a quarter of the state legislature would reject the income tax amendment, but the country shifted in a progressive direction after 1909.

Roosevelt had supported U.S. Steel's acquisition of the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company as a means of preventing the deepening of the Panic of 1907, a decision the former president defended when testifying at the hearings.

[52] In October 1911, Taft's Justice Department brought suit against U.S. Steel, demanding that over a hundred of its subsidiaries be granted corporate independence, and naming as defendants many prominent business executives and financiers.

[55] Roosevelt was an ardent conservationist, assisted in this by like-minded appointees, including Interior Secretary James R. Garfield and Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot.

In 1902, Idaho entrepreneur Clarence Cunningham had made mining claims to coal deposits in Alaska, and a government investigation into the matter lasted throughout Roosevelt's presidency.

[58] In September 1909, Glavis made his allegations public in a magazine article, disclosing that Ballinger had acted as an attorney for Cunningham between his two periods of government service.

[59] In January 1910, Pinchot forced the issue by sending a letter to Senator Jonathan Dolliver alleging that but for the actions of the Forestry Service, Taft would have approved a fraudulent claim on public lands.

According to Pringle, this "was an utterly improper appeal from an executive subordinate to the legislative branch of the government and an unhappy president prepared to separate Pinchot from public office".

[63] A congressional investigation followed, which cleared Ballinger by majority vote, but the administration was embarrassed when Glavis' attorney, Louis D. Brandeis, proved that the Wickersham report had been backdated, which Taft belatedly admitted.

Though the idea was opposed by conservative Republicans such as Senator Aldrich and Speaker of the House Joseph Cannon, Taft won passage of a law establishing the United States Postal Savings System.

[88] Partly due to the backlash over the high rates of the Payne-Aldrich Tariff, Taft urged the adoption of a free trade accord with Canada.

[90][91] Taft and Secretary of State Knox instituted a policy of Dollar Diplomacy towards Latin America, believing U.S. investment would benefit all involved and minimize European influence in the area.

Díaz faced strong political opposition from Francisco I. Madero, who was backed by a sizeable proportion of the population,[99] and was also confronted with serious social unrest sparked by Emiliano Zapata in the south and by Pancho Villa in the north.

[108][109] After the Chinese Revolution broke out, the revolt's leaders chose Sun Yat Sen as provisional president of what became the Republic of China, overthrowing the Manchu Dynasty.

The U.S. House of Representatives in February 1912 passed a resolution supporting a Chinese republic, but Taft and Knox felt recognition should come as a concerted action by Western powers.

Lodge thought that the treaties impinged on senatorial prerogatives,[113] while Roosevelt sought to sabotage Taft's campaign promises[114] and believed that arbitration was a naïve solution and that great issues had to be decided by warfare.

These included a settlement of the boundary between Maine and New Brunswick, a long-running dispute over seal hunting in the Bering Sea that also involved Japan, and a similar disagreement regarding fishing off Newfoundland.

According to Lewis L. Gould in 2009: Taft's dollar diplomacy approach remains fascinating to students of international affairs....The paternalism and cultural condescension that animated Taft and Philander Knox in Latin America continue to draw scorn from recent writers in this area....He insisted that the United States would not intervene in revolutionary Mexico without the approval of Congress, which he knew would not be forthcoming.

Roosevelt called for the "elimination of corporate expenditures for political purposes, physical valuation of railroad properties, regulation of industrial combinations, establishment of an export tariff commission, a graduated income tax ... workmen's compensation laws, state and national legislation to regulate the [labor] of women and children, and complete publicity of campaign expenditure".

Roosevelt believed these manifestations of public support represented a broader movement that would sweep him to the White House with a mandate to implement progressive policies.

In January (two months after the election), the Republican National Committee named Columbia University president Nicholas Murray Butler to replace Sherman and to receive his electoral votes.