Primate cognition

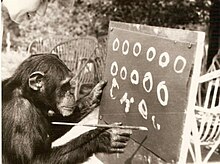

[1] Primates are capable of high levels of cognition; some make tools and use them to acquire foods and for social displays;[2][3] some have sophisticated hunting strategies requiring cooperation, influence and rank;[4] they are status conscious, manipulative and capable of deception;[5] they can recognise kin and conspecifics;[6][7] they can learn to use symbols and understand aspects of human language including some relational syntax, concepts of number and numerical sequence.

[11] Recently, most non-human theory of mind research has focused on monkeys and great apes, who are of most interest in the study of the evolution of human social cognition.

[22] Experimenters since then, such as demonstrated in Krupenye et al. (2016), have gone to extensive lengths to control for behavioral cues by placing the apes in novel settings as suggested by Povinelli and colleagues.

Research has shown that there is substantial evidence for some non-human primates to track the mental state, like desires and beliefs, of other individuals that cannot be deduced to a response of learned behavioural cues.

In the seminal study on vervet monkeys, researchers played recordings of three different types of vocalizations they use as alarm calls for leopards, eagles, and pythons.

The use of recorded sounds, as opposed to observations in the wild, gave researchers insight into the fact that these calls contain meaning about the external world.

Further research into this phenomenon has discovered that infant vervet monkeys produce alarm calls for a wider variety of species than adults.

Diana monkeys were studied in a habituation-dishabituation experiment that demonstrated the ability to attend to the semantic content of calls rather than simply to acoustic nature.

If they deem a leopard is the more likely predator in the vicinity they will produce their own leopard-specific alarm call but if they think it is a human, they will remain silent and hidden.

Research in 2007 shows that chimpanzees in the Fongoli savannah sharpen sticks to use as spears when hunting, considered the first evidence of systematic use of weapons in a species other than humans.

Scientists filmed a large male mandrill at Chester Zoo (UK) stripping down a twig, apparently to make it narrower, and then using the modified stick to scrape dirt from underneath its toenails.

One study suggests that primates could use tools due to environmental or motivational clues, rather than an understanding of folk physics or a capacity for future planning.

Köhler concluded that the chimps had not arrived at these methods through trial-and-error (which American psychologist Edward Thorndike had claimed to be the basis of all animal learning, through his law of effect), but rather that they had experienced an insight (sometimes known as the Eureka effect or an "aha" experience), in which, having realized the answer, they then proceeded to carry it out in a way that was, in Köhler's words, "unwaveringly purposeful."

A principal component analysis run in a meta-analysis of 4,000 primate behaviour papers including 62 species found that 47% of the individual variance in cognitive ability tests was accounted for by a single factor, controlling for socio-ecological variables.

A 2012 study identifying individual chimpanzees that consistently performed highly on cognitive tasks found clusters of abilities instead of a general factor of intelligence.