First Crusade

While Jerusalem had been under Muslim rule for hundreds of years, by the 11th century the Seljuk takeover of the region threatened local Christian populations, pilgrimages from the West, and the Byzantine Empire itself.

The earliest initiative for the First Crusade began in 1095 when Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos requested military support from the Council of Piacenza in the empire's conflict with the Seljuk-led Turks.

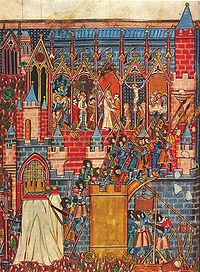

This was followed later in the year by the Council of Clermont, during which Pope Urban II supported the Byzantine request for military assistance and also urged faithful Christians to undertake an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

During the century following the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad in 632, Muslim forces captured Jerusalem and the Levant, North Africa, and most of the Iberian Peninsula, all of which had previously been under Christian rule.

Society was organized by manorialism and feudalism, political structures whereby knights and other nobles owed military service to their overlords in return for the right to rent from lands and manors.

In 1054 differences in custom, creed and practice spurred Pope Leo IX to send a legation to Patriarch Michael I Cerularius of Constantinople, which ended in mutual excommunication and an East–West Schism.

The Christian realms of León, Navarre and Catalonia lacked a common identity and shared history based on tribe or ethnicity so they frequently united and divided during the 11th and 12th centuries.

In 1063, William VIII of Aquitaine led a combined force of French, Aragonese and Catalan knights in the Siege of Barbastro, taking the city that had been in Muslim hands since the year 711.

Normans in Italy; Pechenegs, Serbs and Cumans to the north; and Seljuk Turks in the east all competed with the Empire, and to meet these challenges the emperors recruited mercenaries, even on occasion from their enemies.

[19] This was a difference that weakened power structures when combined with the Seljuks' habitual governance of territory based on political preferment and competition between independent princes rather than geography.

Romanos IV Diogenes attempted to suppress the Seljuks' sporadic raiding, but was defeated at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the only time in history that a Byzantine emperor became the prisoner of a Muslim commander.

When Tutush was killed in 1095, his sons Ridwan and Duqaq inherited Aleppo and Damascus, respectively, further dividing Syria amongst emirs antagonistic towards each other, as well as Kerbogha, the atabeg of Mosul.

[22] According to historian Jonathan Riley-Smith and Rodney Stark, Muslim authorities in the Holy Land often enforced harsh rules "against any open expressions of the Christian faith":[23] [24][25][26] In 1026 Richard of Saint-Vanne was stoned to death after he was seen saying Mass.

"[28] It was in this climate that the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos wrote a letter to Robert II of Flanders saying: The holy places are desecrated and destroyed in countless ways.

[29]The emperor warned that if Constantinople fell to the Turks, not only would thousands more Christians be tortured, raped and murdered, but “the most holy relics of the Saviour,” gathered over the centuries, would be lost.

[42] Urban had planned the departure of the first crusade for 15 August 1096, the Feast of the Assumption, but months before this, a number of unexpected armies of peasants and petty nobles set off for Jerusalem on their own, led by a charismatic priest called Peter the Hermit.

[47] Peter's and Walter's unruly mob began to pillage outside the city in search of supplies and food, prompting Alexios to hurriedly ferry the gathering across the Bosporus one week later.

A decade before, the Bishop of Speyer had taken the step of providing the Jews of that city with a walled ghetto to protect them from Christian violence and given their chief rabbis the control of judicial matters in the quarter.

He had discussed the crusade with Adhemar of Le Puy[56] and Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse,[57] and instantly the expedition had the support of two of southern France's most important leaders.

In the end, most who took up the call were not knights, but peasants who were not wealthy and had little in the way of fighting skills, in an outpouring of a new emotional and personal piety that was not easily harnessed by the ecclesiastical and lay aristocracy.

Alexios was understandably suspicious after his experiences with the People's Crusade, and also because the knights included his old Norman enemy, Bohemond, who had invaded Byzantine territory on numerous occasions with his father and may have even attempted to organize an attack on Constantinople while encamped outside the city.

[80] Hoping rather to force a capitulation, or find a traitor inside the city—a tactic that had previously seen Antioch change to the control of the Byzantines and then the Seljuk Turks—the crusader army began a siege on 20 October 1097.

Morale inside the city was low and defeat looked imminent but a peasant visionary called Peter Bartholomew claimed the apostle St, Andrew came to him to show the location of the Holy Lance that had pierced Christ on the cross.

In January, Raymond dismantled the walls of Ma'arrat al-Numan, and he began the march south to Jerusalem, barefoot and dressed as a pilgrim, followed by Robert and Tancred and their respective armies.

[113] After a three-day fast, on 8 July the Crusaders performed the procession as they had been instructed by Desiderius, ending on the Mount of Olives where Peter the Hermit preached to them,[119] and shortly afterwards the various bickering factions arrived at a public rapprochement.

[143] American historian August Krey has created a narrative The First Crusade: The Accounts of Eyewitnesses and Participants,[144] verbatim from the various chronologies and letters which offers considerable insight into the endeavour.

These histories used primary source materials, but they used them selectively to talk of Holy War (bellum sacrum), and their emphasis was upon prominent individuals and upon battles and the intrigues of high politics.

French historian Jean-François-Aimé Peyré expanded Michaud's work on the First Crusade with his Histoire de la Première Croisade, a 900-page, two-volume set with extensive sourcing.

[190] The first of these is Crusades,[191][137] by French historian Louis R. Bréhier, appearing in the Catholic Encyclopedia, based on his L'Église et l'Orient au Moyen Âge: Les Croisades.

Additional background chapters on related events of the 11th century are: Western Europe, by Sidney Painter; the Byzantine Empire, by Peter Charanis; the Islamic world by H. A.