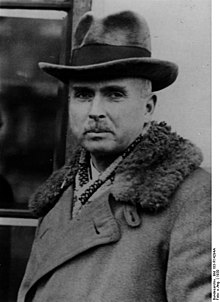

Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

[3] Charles Edward's mother, Princess Helen, Duchess of Albany, was the daughter of the ruling prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont, George Victor, and the sister of Queen Emma of the Netherlands.

[8] Queen Victoria's immediate family belonged to the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha; her deceased husband, Prince Albert, was the younger brother of the childless Duke Ernest II.

He described it as:... a small, self-contained world of early-to-rise, porridge for breakfast, vigorous hair-brushings, buttoned boots, holland pinafores, pick-a-back rides, stories, squabbles, tears, treats and punishments, bland nursery meals, walks to the lake to feed the wild ducks with squares of dry bread ... , little covered baskets holding soup or jelly or junket for the sick, pony rides in the park, baths filled with hot water from highly polished copper cans, firelight, lamplight, warming-pans, good-night prayers, nightlights.

Recently his bride, Princess Victoria and her parents were also present; This probably made it particularly embarrassing for the poor little Duke, who almost fought back tears and had such an unhappy expression on his face the whole evening, as if he were about to be hanged the next morning.

[62][10] Charlotte Zeepzat, author of his entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB), described him as a "conscientious young man with a taste for the arts and music", who became popular in Coburg during this period.

[7] Aronson similarly commented that although Charles Edward had "grown to maturity in an atmosphere of strident Prussian militarism", he was "cultivated ... fond of music and the theatre, interested in history and architecture".

[79] Historian Juliet Nicolson has described these years as "the perfect summer"—a time when privileged people enjoyed their wealth and social advantages in denial of the threats to their way of life that were starting to appear in politics and organised labour.

[90] He told his sister that he wanted to fight for Great Britain but felt obligated to return to his duchy, where public opinion began to turn against the Duke due to his British origins.

[94] Over the summer of 1917 bombers built in Gotha, which were named after the town, conducted multiple air raids in London and South East England which killed several hundred British civilians.

The duchy's prime minister, Hermann Quarck [de], convinced the local SPD, which had many relatively well-off members, that further unrest would be dangerous to the town's scenery.

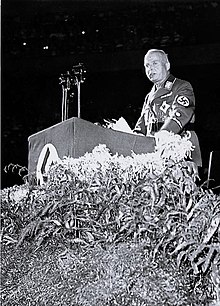

Charles Edward was made president of the National Socialist Automobile Association, an organisation which provided vehicles for the German state, including those used to carry out the Holocaust.

The dispute over properties in Thuringia and Austria, which had been confiscated by the state authorities after the end of the First World War, was soon resolved in favour of the ducal family, not least through the intervention of high-ranking National Socialist party members.

Rushton commented that "Two years after the founding of the new regime, the DRK [German Red Cross] was remodelled into a paramilitary organization with the goal of providing support for soldiers in a time of conflict".

Charles Edward helped arrange for his friend, President of the International Red Cross Carl Jacob Burckhardt, to make a tightly controlled tour of the concentration camps, including Dachau, in 1935.

[153] Eugenics—the fringe theory that a human population can be "improved" over generations by encouraging some people to have children and discouraging others—was a concept that originated in the 19th century and became increasingly popular among German academic circles in the decades before the Nazis came to power.

[156] The Great Depression intensified concern that disabled people were a drain on public resources, with scientists and non-Nazi politicians increasingly discussing the idea of voluntary sterilisation for these groups.

[9] The British Secretary of State for War, Duff Cooper described a party that was organised on Charles Edward's behalf at Alice's country home in 1936;The point of it was to meet the Duke of Coburg, her brother.

In the middle of our conversation his Duchess [Victoria Adelaide] reappeared carrying some hideous samples of ribbon in order to consult him as to how the wreath that they were sending to the funeral [of George V's] should be tied.

[184] In 1942, Charles Edward was asked by his relative Prince Eugene of Sweden to arrange for Martha Liebermann, an elderly Jewish woman, to be granted permission to emigrate to the United States.

Charles Edward spent the last years of his life in seclusion, forced into relative poverty by the fines he had been required to pay by the denazification tribunal,[208] and the seizure of much of his property by the Soviets.

The Duke replied that, although his health did not allow him to accept, he was deeply touched by the invitation, "renewing old connections which existed between the Seaforth Highlanders and myself for so many years, and which I honestly hope and wish will not be severed again".

[215] In his biography of Alice, published in 1981, Aronson commented that some members of the British royal family felt that Charles Edward had supported the regime "due to his conviction that Hitler had saved Germany from Communism".

Urbach wrote that there was some disagreement among the production team of the 2007 documentary, on whether Charles Edward should be portrayed as a man who struggled with politics in a country that was foreign to him, or as an ideological Nazi, and that this led to a contradictory depiction of his character.

Urbach argued that Charles Edward had a similar kind of character to Hitler, commenting that the two men shared "ideologies and of course their narcissistic personalities (the only creatures they both declared a fondness for were their dogs)."

A review in The Times commented on Charles Edward that: For many years thereafter [the German Revolution], Carl Eduard was regarded as a mere footnote in history; a harmless, potty old aristocrat, washed up by the seismic upheavals of the early 20th century.

[221]Büschel suggested in his 2016 biography of Charles Edward that the various pressures placed on the nobleman from childhood until the outcome of the First World War may have led to him developing split personality disorder and narcissism.

[222] Rushton, in his 2018 book about the former duke's relationship to the murder of disabled people, described Charles Edward's life as "the story of a man born to royalty who became ensnared in the politics of human destruction.

Rushton noted that Charles Edward had already lost his status as a British prince and German duke, making his new identity as a Nazi party leader deeply emotionally important to him.

He argued that this "... reflects a moral character defect... low self-esteem and little self-respect ... [lack of action is often due to] fear of others' opinions in the community and the risk to one's comfortable and secure lifestyle".

The commission, which reported its findings in 2024, noted that Charles Edward was an influential figure in the town, and that his support for Volkisch organisations contributed to the growth of far-right politics.