German Empire

[34] The consequential economic devastation, later exacerbated by the Great Depression, as well as humiliation and outrage experienced by the German population are considered leading factors in the rise of Adolf Hitler and Nazism.

The patriotic fervor generated by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 overwhelmed the remaining opposition to a unified Germany (aside from Austria) in the four states south of the Main, and during November 1870, they joined the North German Confederation by treaty.

One factor in the social anatomy of these governments was the retention of a very substantial share in political power by the landed elite, the Junkers, resulting from the absence of a revolutionary breakthrough by the peasants in combination with urban areas.

The king and (with two exceptions) the prime minister of Prussia were also the emperor and chancellor of the empire – meaning that the same rulers had to seek majorities from legislatures elected from completely different franchises.

British historian Eric Hobsbawm concludes that he "remained undisputed world champion at the game of multilateral diplomatic chess for almost twenty years after 1871, [devoting] himself exclusively, and successfully, to maintaining peace between the powers".

[45] This was a departure from his adventurous foreign policy for Prussia, where he favored strength and expansion, punctuating this by saying, "The great questions of the age are not settled by speeches and majority votes – this was the error of 1848–49 – but by iron and blood.

In 1886, he moved to stop an attempted sale of horses to France because they might be used for cavalry and also ordered an investigation into large Russian purchases of medicine from a German chemical works.

Bismarck stubbornly refused to listen to Georg Herbert Münster, ambassador to France, who reported back that the French were not seeking a revanchist war and were desperate for peace at all costs.

The construction of the Berlin–Baghdad railway, financed by German banks, was designed to eventually connect Germany with the Ottoman Empire and the Persian Gulf, but it also collided with British and Russian geopolitical interests.

[50] By the 1890s, German colonial expansion in Asia and the Pacific (Jiaozhou Bay and Tianjin in China, the Marianas, the Caroline Islands, Samoa) led to frictions with the UK, Russia, Japan, and the US.

The three major firms had also integrated upstream into the production of essential raw materials and they began to expand into other areas of chemistry such as pharmaceuticals, photographic film, agricultural chemicals and electrochemicals.

Top-level decision-making was in the hands of professional salaried managers; leading Chandler to call the German dye companies "the world's first truly managerial industrial enterprises".

Unlike the situation in France, the goal was support of industrialisation, and so heavy lines crisscrossed the Ruhr and other industrial districts and provided good connections to the major ports of Hamburg and Bremen.

He opposed Catholic civil rights and emancipation, especially the influence of the Vatican under Pope Pius IX, and working-class radicalism, represented by the emerging Social Democratic Party.

In the face of systematic defiance, the Bismarck government increased the penalties and its attacks, and were challenged in 1875 when a papal encyclical declared the whole ecclesiastical legislation of Prussia was invalid, and threatened to excommunicate any Catholic who obeyed.

[55][74] Bismarck further won the support of both industry and skilled workers by his high tariff policies, which protected profits and wages from American competition, although they alienated the liberal intellectuals who wanted free trade.

Bismarck demanded that the German Army be sent in to crush the strike, but Wilhelm II rejected this authoritarian measure, responding "I do not wish to stain my reign with the blood of my subjects.

[85] Wilhelm became internationally notorious for his aggressive stance on foreign policy and his strategic blunders (such as the Tangier Crisis), which pushed the German Empire into growing political isolation and eventually helped to cause World War I.

The threat of the SPD to the German monarchy and industrialists caused the state both to crack down on the party's supporters and to implement its own programme of social reform to soothe discontent.

Native insurrections in German territories received prominent coverage in other countries, especially in Britain; the established powers had dealt with such uprisings decades earlier, often brutally, and had secured firm control of their colonies by then.

The Boxer Rising in China, which the Chinese government eventually sponsored, began in the Shandong province, in part because Germany, as colonizer at Jiaozhou, was an untested power and had only been active there for two years.

When war came, Italy saw more benefit in an alliance with Britain, France, and Russia, which, in the secret Treaty of London in 1915 promised it the frontier districts of Austria and also colonial concessions.

Subsequent interpretation – for example at the Versailles Peace Conference – was that this "blank cheque" licensed Austro-Hungarian aggression regardless of the diplomatic consequences, and thus Germany bore responsibility for starting the war, or at least provoking a wider conflict.

Facing political opposition, he decided to end Russia's campaign against Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria to redirect Bolshevik energy to eliminating internal dissent.

In March 1918, by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the Bolshevik government gave Germany and the Ottoman Empire enormous territorial and economic concessions in exchange for an end to war on the Eastern Front.

By retraining the soldiers in new infiltration tactics, the Germans expected to unfreeze the battlefield and win a decisive victory before the army of the United States, which had now entered the war on the side of the Allies, arrived in strength.

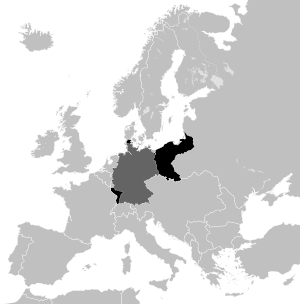

[123] The defeat and aftermath of the First World War and the penalties imposed by the Treaty of Versailles shaped the positive memory of the Empire, especially among Germans who distrusted and despised the Weimar Republic.

The German Empire was for Hans-Ulrich Wehler a strange mixture of highly successful capitalist industrialisation and socio-economic modernisation on the one hand, and of surviving pre-industrial institutions, power relations and traditional cultures on the other.

Recognising the importance of modernising forces in industry and the economy and in the cultural realm, Wehler argues that reactionary traditionalism dominated the political hierarchy of power in Germany, as well as social mentalities and in class relations (Klassenhabitus).

The special circumstances of German historical structures and experiences, were interpreted as preconditions that, while not directly causing National Socialism, did hamper the development of a liberal democracy and facilitate the rise of fascism.