Prisoner of war

[a] Belligerents hold prisoners of war in custody for a range of legitimate and illegitimate reasons, such as isolating them from the enemy combatants still in the field (releasing and repatriating them in an orderly manner after hostilities), demonstrating military victory, punishing them, prosecuting them for war crimes, exploiting them for their labour, recruiting or even conscripting them as their own combatants, collecting military and political intelligence from them, or indoctrinating them in new political or religious beliefs.

Sometimes the purpose of a battle, if not of a war, was to capture women, a practice known as raptio; the Rape of the Sabines involved, according to tradition, a large mass-abduction by the founders of Rome.

[4] In the fourth century AD, Bishop Acacius of Amida, touched by the plight of Persian prisoners captured in a recent war with the Roman Empire, who were held in his town under appalling conditions and destined for a life of slavery, took the initiative in ransoming them by selling his church's precious gold and silver vessels and letting them return to their country.

[5] According to legend, during Childeric's siege and blockade of Paris in 464 the nun Geneviève (later canonised as the city's patron saint) pleaded with the Frankish king for the welfare of prisoners of war and met with a favourable response.

[8] When asked by a Crusader how to distinguish between the Catholics and Cathars following the projected capture (1209) of the city of Béziers, the papal legate Arnaud Amalric allegedly replied, "Kill them all, God will know His own".

[17] On certain occasions where Muhammad felt the enemy had broken a treaty with the Muslims he endorsed the mass execution of male prisoners who participated in battles, as in the case of the Banu Qurayza in 627.

[19] Soldiers whose style of fighting did not conform to the battle line tactics of regular European armies, such as Cossacks and Croats, were often denied the status of prisoners of war.

Some Native Americans continued to capture Europeans and use them both as labourers and as bargaining chips into the 19th century; see for example the case of John R. Jewitt, a sailor who wrote a memoir about his years as a captive of the Nootka people on the Pacific Northwest coast from 1802 to 1805.

Although no agreements were immediately ratified by the participating nations, work was continued that resulted in new conventions being adopted and becoming recognised as international law that specified that prisoners of war be treated humanely and diplomatically.

To qualify under the Third Geneva Convention, a combatant must be part of a chain of command, wear a "fixed distinctive marking, visible from a distance", bear arms openly, and have conducted military operations according to the laws and customs of war.

A January 2008 directive states that the reasoning behind this is since "Prisoner of War" is the international legal recognised status for such people there is no need for any individual country to follow suit.

All nations pledged to follow the Hague rules on fair treatment of prisoners of war, and in general the POWs had a much higher survival rate than their peers who were not captured.

Once prisoners reached a POW camp conditions were better (and often much better than in World War II), thanks in part to the efforts of the International Red Cross and inspections by neutral nations.

The released POWs were met by cavalry troops and sent back through the lines in lorries to reception centres where they were refitted with boots and clothing and dispatched to the ports in trains.

"[70] Life in the POW camps was recorded at great risk to themselves by artists such as Jack Bridger Chalker, Philip Meninsky, Ashley George Old, and Ronald Searle.

[72] Germany and Italy generally treated prisoners from the British Empire and Commonwealth, France, the U.S., and other western Allies in accordance with the Geneva Convention, which had been signed by these countries.

[74] For example, Major Yitzhak Ben-Aharon, a Palestinian Jew who had enlisted in the British Army, and who was captured by the Germans in Greece in 1941, experienced four years of captivity under entirely normal conditions for POWs.

[76] As the US historian Joseph Robert White put it: "An important exception ... is the sub-camp for U.S. POWs at Berga an der Elster, officially called Arbeitskommando 625 [also known as Stalag IX-B].

Two possible reasons have been suggested for this incident: German authorities wanted to make an example of Terrorflieger ("terrorist aviators") or these aircrews were classified as spies, because they had been disguised as civilians or enemy soldiers when they were apprehended.

The conditions were improved in 1942 when, by order of Marshal Ion Antonescu, the organisations leading the camps were to permanently control how the prisoners were accommodated, cared for, fed, and used.

The last German POWs like Erich Hartmann, the highest-scoring fighter ace in the history of aerial warfare, who had been declared guilty of war crimes but without due process, were not released by the Soviets until 1955, two years after Stalin died.

[106] During the war, the armies of Western Allied nations such as Australia, Canada, the UK and the US[107] were given orders to treat Axis prisoners strictly in accordance with the Geneva Convention.

[111] Towards the end of the war in Europe, as large numbers of Axis soldiers surrendered, the US created the designation of Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEF) so as not to treat prisoners as POWs.

After the surrender of Germany in May 1945, the POW status of the German prisoners was in many cases maintained, and they were for several years used as public labourers in countries such as the UK and France.

However, after making appeals to the Allies in the autumn of 1945, the Red Cross was allowed to investigate the camps in the British and French occupation zones of Germany, as well as providing relief to the prisoners held there.

Newspapers reported that the POWs were being mistreated; Judge Robert H. Jackson, chief US prosecutor in the Nuremberg trials, told US President Harry S Truman in October 1945 that the Allies themselves, have done or are doing some of the very things we are prosecuting the Germans for.

[140] At the end of the First Indochina War, of the 11,721 French soldiers taken prisoner after the Battle of Dien Bien Phu and led by the Viet Minh on death marches to distant POW camps, only 3,290 were repatriated four months later.

As in previous conflicts, speculation existed, without evidence, that a handful of American pilots captured during the Korean and Vietnam wars were transferred to the Soviet Union and never repatriated.

[147] In 1991, during the Gulf War, American, British, Italian, and Kuwaiti POWs (mostly crew members of downed aircraft and special forces) were tortured by the Iraqi secret police.

A large number of surviving Croatian or Bosnian POWs described the conditions in Serbian concentration camps as similar to those in Germany in World War II, including regular beatings, torture and random executions.

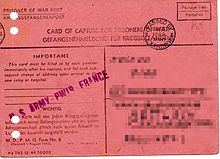

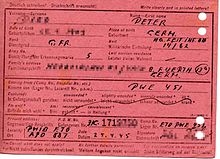

of a German General

(Front- and Backside)