Procopius Waldvogel

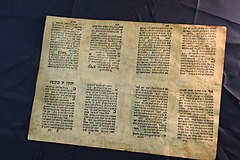

[5][6] Waldvogel's name appears in several contracts of that time, most notably the one in which he agrees to provide Davin de Caderousse with equipment for reproducing Hebrew texts.

[11][12] In 1896, Dutch historian Antonius van der Linde [nl] refuted Requin's claims, giving several arguments why Waldvogel cannot be regarded as the inventor of printing: (1) the monetary amounts mentioned in the documents were far too small for Waldvogel to be able to establish a proper printing press; (2) the steel double alphabet, along with the 48 types—one set made of tin and another of iron—and the 27 Hebrew letters mentioned, were too few to be considered proper fonts.

They also were not typographical molds, as neither the students nor the dyers could use them without the crucial tool: the casting mold; (3) the nature of the demanded secrecy, once for a radius of 12 miles, and another time for a radius of 30 miles, does not point to a technology as complicated as typography; (4) the kind of instruction and remuneration that were given do not suggest that a real printing press was ever created; (5) it is unlikely that the six typographers present in Avignon (from 1444 to 1446, including Waldvogel) could have disappeared without a trace.

The study of their watermarks, paper, ink, typeset typography, made upon request of their owner, concluded that it may be possible that they could have been printed in the area of Avignon around 1444, suggesting that they might be Waldvogel and Davin de Caderousse's work.

This finding has received some media coverage, although in the absence of a counter-expertise by independent scholars, the putative link between these printed quires and Waldfogel's entreprise remains purely speculative.