Projective polyhedron

The best-known examples of projective polyhedra are the regular projective polyhedra, the quotients of the centrally symmetric Platonic solids, as well as two infinite classes of even dihedra and hosohedra:[4] These can be obtained by taking the quotient of the associated spherical polyhedron by the antipodal map (identifying opposite points on the sphere).

Note that the prefix "hemi-" is also used to refer to hemipolyhedra, which are uniform polyhedra having some faces that pass through the center of symmetry.

Of these uniform hemipolyhedra, only the tetrahemihexahedron is topologically a projective polyhedron, as can be verified by its Euler characteristic and visually obvious connection to the Roman surface.

Further, because a covering map is a local homeomorphism (in this case a local isometry), both the spherical and the corresponding projective polyhedra have the same abstract vertex figure.

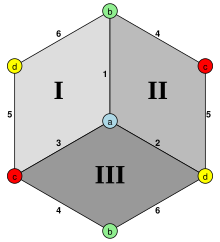

For example, the 2-fold cover of the (projective) hemi-cube is the (spherical) cube.

The hemi-cube has 4 vertices, 3 faces, and 6 edges, each of which is covered by 2 copies in the sphere, and accordingly the cube has 8 vertices, 6 faces, and 12 edges, while both these polyhedra have a 4.4.4 vertex figure (3 squares meeting at a vertex).

Spherical polyhedra without central symmetry do not define a projective polyhedron, as the images of vertices, edges, and faces will overlap.

This geometrizes the Galois connection at the level of finite subgroups of O(3) and PO(3), under which the adjunction is "union with central inverse".

The cover of this is the stellated octahedron – equivalently, the compound of two tetrahedra – which has 8 vertices, 12 edges, and 8 faces, and vertex figure 3.3.3.

Defining k-dimensional projective polytopes in n-dimensional projective space is somewhat trickier, because the usual definition of polytopes in Euclidean space requires taking convex combinations of points, which is not a projective concept, and is infrequently addressed in the literature, but has been defined, such as in (Vives & Mayo 1991).

Thus in particular the symmetry group of a projective polyhedron is the rotational symmetry group of the covering spherical polyhedron; the full symmetry group of the spherical polyhedron is then just the direct product with reflection through the origin, which is the kernel on passage to projective space.

and is instead a proper (index 2) subgroup, so there is a distinct notion of orientation-preserving isometries.

The projectivization of a 2r-gon (in the circle) is an r-gon (in the projective line), and accordingly the quotient groups, subgroups of PO(2) and PSO(2) are Dihr and Cr.

Note that the same commutative square of subgroups occurs for the square of Spin group and Pin group – Spin(2), Pin+(2), SO(2), O(2) – here going up to a 2-fold cover, rather than down to a 2-fold quotient.

) as the sphere is simply connected, and thus there is no corresponding "binary polytope" for which subgroups of Pin are symmetry groups.