Abstract polytope

For example, a square and a trapezoid both comprise an alternating chain of four vertices and four sides, which makes them quadrilaterals.

The term face is used to refer to any such element e.g. a vertex (0-face), edge (1-face) or a general k-face, and not just a polygonal 2-face.

[3] The faces of the abstract quadrilateral or square are shown in the table below: The relation < comprises a set of pairs, which here include Order relations are transitive, i.e. F < G and G < H implies that F < H. Therefore, to specify the hierarchy of faces, it is not necessary to give every case of F < H, only the pairs where one is the successor of the other, i.e. where F < H and no G satisfies F < G < H. The edges W, X, Y and Z are sometimes written as ab, ad, bc, and cd respectively, but such notation is not always appropriate.

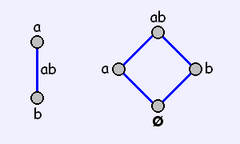

The Hasse diagram defines the unique poset and therefore fully captures the structure of the polytope.

The rank of a face or polytope usually corresponds to the dimension of its counterpart in traditional theory.

The above condition ensures that a pair of disjoint triangles abc and xyz is not a (single) polytope.

A polytope can only be fully described using vertex notation if every face is incident with a unique set of vertices.

Four examples of non-traditional abstract polyhedra are the Hemicube (shown), Hemi-octahedron, Hemi-dodecahedron, and the Hemi-icosahedron.

Abstractly, the dual is the same polytope but with the ranking reversed in order: the Hasse diagram differs only in its annotations.

Hence, the Hasse diagram of a self-dual polytope must be symmetrical about the horizontal axis half-way between the top and bottom.

Formally, an abstract polytope is defined to be "regular" if its automorphism group acts transitively on the set of its flags.

For example, any abstract polygon is regular, since angles, edge-lengths, edge curvature, skewness etc.

There are several other weaker concepts, some not yet fully standardized, such as semi-regular, quasi-regular, uniform, chiral, and Archimedean that apply to polytopes that have some, but not all of their faces equivalent in each rank.

[5][6] Two realizations are called congruent if the natural bijection between their sets of vertices is induced by an isometry of their ambient Euclidean spaces.

[7][8] If an abstract n-polytope is realized in n-dimensional space, such that the geometrical arrangement does not break any rules for traditional polytopes (such as curved faces, or ridges of zero size), then the realization is said to be faithful.

In general, only a restricted set of abstract polytopes of rank n may be realized faithfully in any given n-space.

The group G of symmetries of a realization V of an abstract polytope P is generated by two reflections, the product of which translates each vertex of P to the next.

[11][10] Generally, the moduli space of realizations of an abstract polytope is a convex cone of infinite dimension.

[12][13] The realization cone of the abstract polytope has uncountably infinite algebraic dimension and cannot be closed in the Euclidean topology.

Given this fact, the search for polytopes with particular facets and vertex figures usually goes as follows: These two problems are, in general, very difficult.

Except for the universal polytope itself, they all correspond to various ways to tessellate either a torus or an infinitely long cylinder with squares.

Since its facets are, topologically, projective planes instead of spheres, the 11-cell is not a tessellation of any manifold in the usual sense.

This is in keeping with the common intuition that the Platonic solids are three dimensional, even though they can be regarded as tessellations of the two-dimensional surface of a ball.

It does not allow an easy way to describe a polytope whose facets are tori and whose vertex figures are projective planes, for example.

However, much progress has been made on the complete classification of the locally toroidal regular polytopes [15] Let Ψ be a flag of an abstract n-polytope, and let −1 < i < n. From the definition of an abstract polytope, it can be proven that there is a unique flag differing from Ψ by a rank i element, and the same otherwise.

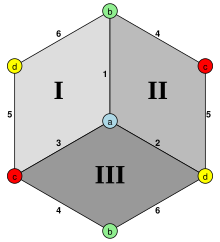

This numerative usage enables a symmetry grouping, as in the Hasse Diagram of the square pyramid: If vertices B, C, D, and E are considered symmetrically equivalent within the abstract polytope, then edges f, g, h, and j will be grouped together, and also edges k, l, m, and n, And finally also the triangles P, Q, R, and S. Thus the corresponding incidence matrix of this abstract polytope may be shown as: In this accumulated incidence matrix representation the diagonal entries represent the total counts of either element type.

Already this simple square pyramid shows that the symmetry-accumulated incidence matrices are no longer symmetrical.

With the earlier work by Branko Grünbaum, H. S. M. Coxeter and Jacques Tits having laid the groundwork, the basic theory of the combinatorial structures now known as abstract polytopes was first described by Egon Schulte in his 1980 PhD dissertation.

Subsequently, he and Peter McMullen developed the basics of the theory in a series of research articles that were later collected into a book.

Numerous other researchers have since made their own contributions, and the early pioneers (including Grünbaum) have also accepted Schulte's definition as the "correct" one.