Pronoun

Pronouns have traditionally been regarded as one of the parts of speech, but some modern theorists would not consider them to form a single class, in view of the variety of functions they perform cross-linguistically.

A prop-word is a word with little or no semantic content used where grammar dictates a certain sentence member, e.g., to provide a "support" on which to hang a modifier.

The word most commonly considered as a prop-word in English is one (with the plural form ones).

The pronoun is described there as "a part of speech substitutable for a noun and marked for a person."

Pronouns continued to be regarded as a part of speech in Latin grammar (the Latin term being pronomen, from which the English name – through Middle French – ultimately derives), and thus in the European tradition generally.

Because of the many different syntactic roles that they play, pronouns are less likely to be a single word class in more modern approaches to grammar.

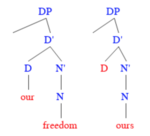

[1] Certain types of pronouns are often identical or similar in form to determiners with related meaning; some English examples are given in the table.

[7] (Such patterning can even be claimed for certain personal pronouns; for example, we and you might be analyzed as determiners in phrases like we Brits and you tennis players.)

The distinction may be considered to be one of subcategorization or valency, rather like the distinction between transitive and intransitive verbs – determiners take a noun phrase complement like transitive verbs do, while pronouns do not.

Cross-linguistically, it seems as though pronouns share 3 distinct categories: point of view, person, and number.

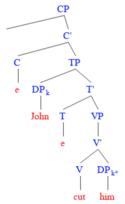

In this binding context, reflexive and reciprocal pronouns in English (such as himself and each other) are referred to as anaphors (in a specialized restricted sense) rather than as pronominal elements.

Under binding theory, specific principles apply to different sets of pronouns.

The type of binding that applies to subsets of pronouns varies cross-linguistically.

[2]: 55–56 Reflexive pronouns are used when a person or thing acts on itself, for example, John cut himself.

Demonstrative pronouns (in English, this, that and their plurals these, those) often distinguish their targets by pointing or some other indication of position; for example, I'll take these.

They may also be anaphoric, depending on an earlier expression for context, for example, A kid actor would try to be all sweet, and who needs that?

One group in English includes compounds of some-, any-, every- and no- with -thing, -one and -body, for example: Anyone can do that.

[2]: 56–57 In English and many other languages (e.g. French and Czech), the sets of relative and interrogative pronouns are nearly identical.

Though one would rarely find these older forms used in recent literature, they are nevertheless considered part of Modern English.

In English, kin terms like "mother", "uncle", "cousin" are a distinct word class from pronouns; however many Australian Aboriginal languages have more elaborated systems of encoding kinship in language including special kin forms of pronouns.

In Murrinh-patha, for example, when selecting a nonsingular exclusive pronoun to refer to a group, the speaker will assess whether or not the members of the group belong to a common class of gender or kinship.

See the following example: Pulalakiya3DU.KINpanti-rda.fight-PRESPulalakiya panti-rda.3DU.KIN fight-PRESThey two [who are in the classificatory relationship of father and son] are fighting.