Proofs of trigonometric identities

There are several equivalent ways for defining trigonometric functions, and the proofs of the trigonometric identities between them depend on the chosen definition.

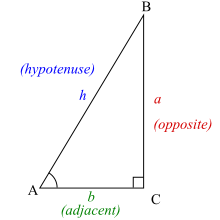

The oldest and most elementary definitions are based on the geometry of right triangles and the ratio between their sides.

For greater and negative angles, see Trigonometric functions.

Other definitions, and therefore other proofs are based on the Taylor series of sine and cosine, or on the differential equation

Or Two angles whose sum is π/2 radians (90 degrees) are complementary.

In the diagram, the angles at vertices A and B are complementary, so we can exchange a and b, and change θ to π/2 − θ, obtaining: Identity 1: The following two results follow from this and the ratio identities.

Similarly Identity 2: The following accounts for all three reciprocal functions.

Proof 2: Refer to the triangle diagram above.

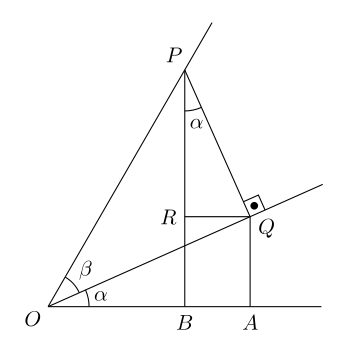

Substituting with appropriate functions - Rearranging gives: Draw a horizontal line (the x-axis); mark an origin O.

Draw R on PB so that QR is parallel to the x-axis.

and using the reflection identities of even and odd functions, we also get: Using the figure above, By substituting

and using the reflection identities of even and odd functions, we also get: Also, using the complementary angle formulae, From the sine and cosine formulae, we get Dividing both numerator and denominator by

, Similarly, from the sine and cosine formulae, we get Then by dividing both numerator and denominator by

, From the angle sum identities, we get and The Pythagorean identities give the two alternative forms for the latter of these: The angle sum identities also give It can also be proved using Euler's formula Squaring both sides yields But replacing the angle with its doubled version, which achieves the same result in the left side of the equation, yields It follows that Expanding the square and simplifying on the left hand side of the equation gives Because the imaginary and real parts have to be the same, we are left with the original identities and also The two identities giving the alternative forms for cos 2θ lead to the following equations: The sign of the square root needs to be chosen properly—note that if 2π is added to θ, the quantities inside the square roots are unchanged, but the left-hand-sides of the equations change sign.

Therefore, the correct sign to use depends on the value of θ.

For the tan function, the equation is: Then multiplying the numerator and denominator inside the square root by (1 + cos θ) and using Pythagorean identities leads to: Also, if the numerator and denominator are both multiplied by (1 - cos θ), the result is: This also gives: Similar manipulations for the cot function give: If

quarter circle, Proof: Replace each of

with their complementary angles, so cotangents turn into tangents and vice versa.

Given so the result follows from the triple tangent identity.

Therefore, Similarly for cosine, start with the sum-angle identities: Again, by adding and subtracting Substitute

as before, The figure at the right shows a sector of a circle with radius 1.

The area of triangle OAD is AB/2, or sin(θ)/2.

The area of triangle OCD is CD/2, or tan(θ)/2.

Since triangle OAD lies completely inside the sector, which in turn lies completely inside triangle OCD, we have This geometric argument relies on definitions of arc length and area, which act as assumptions, so it is rather a condition imposed in construction of trigonometric functions than a provable property.

So we have For negative values of θ we have, by the symmetry of the sine function Hence and In other words, the function sine is differentiable at 0, and its derivative is 1.

All these functions follow from the Pythagorean trigonometric identity.

We can prove for instance the function Proof: We start from Then we divide this equation (I) by

And initial Pythagorean trigonometric identity proofed...

And initial Pythagorean trigonometric identity proofed...

... And finally we have [arccos] expressed through [arctan]...