Propaganda in World War II

Goebbels, before committing suicide, remarked, "Enemy propaganda is beginning to have an uncomfortably noticeable effect on the German people.... British broadcasts have a grateful audience".

[3] The British used black propaganda techniques to deliver subversive messages directly to the German people by dropping leaflets and postcards.

[3] The Hollywood film Mrs. Miniver (1942) by William Wyler told the saga of the British home front and ended with a sermon delivered in a church destroyed by Allied bombs: "This is the people's war.

Goebbels, who was appointed by Adolf Hitler to lead the ministry, used radio, press, books, films, and all other forms of communication media to promote the Nazi ideology.

During Operation Barbarossa, the 12th Infantry Division of the Wehrmacht were served by a travelling "radio van" that made the rounds carrying a very powerful receiver.

However, after the Pearl Harbor attack, the Office of War Information, the main source of propaganda was created by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1942.

Some of the propaganda has been criticized as having racially charged content, such as the films of Frank Capra Why We Fight, which showed the enemy nations as inhuman.

The involvement of the OWI in Hollywood has been noted for the creation of patriotic propaganda films such as Yankee Doodle Dandy, Pin-Up Girl, and Anchors Aweigh.

Popeye and Bugs Bunny were shown fighting the Japanese, and a short film of Donald Duck attacking Hitler with a tomato was released by Walt Disney.

[3] At home, Roosevelt's wartime propaganda supported the war by generating more soldiers, keeping the morale, and maintaining civilian workforce and production.

Against the Axis powers, the comic characters fought to protect the United States and instilled patriotic themes to further sell the war to Americans.

[12] One example depicts Emperor Hirohoto as a fanged bat designed with exaggerated features, dressed in Nazi clothing and swastikas, to dehumanise the Japanese enemy further to the American people.

[15] The Office of War Information went on to engage in a propaganda campaign aimed to generate a sense of belonging and loyalty with America and African-Americans.

[16] An initial piece of propaganda in 1942, 2.5 million pamphlets of "Negros and the War," was largely distributed and argued that without America, African-Americans could not fight for their freedoms.

[16] The Office of War Information also co-operated with Hollywood movie producers to try to depict African-Americans as integral and normal in films,[17] such as in Stormy Weather and Cabin in the Sky.

[18] In the film Bataan, an African-American soldier dies heroically after he is involved in an earlier scene in discussing strategy and his American patriotism with his white platoon.

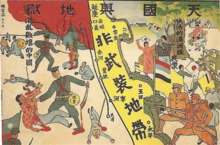

[25] Japanese propaganda commonly operated to demoralise Allied troops and often employed racial themes to degrade western culture's oppression of Japan.

[31] Soviet newspapers “encouraged hatred” from the states of the union by presenting Poland as having “brutalised millions of Belorussians, Ukrainians, and Jews”.

[33] Soviet propaganda, during the country's victory at Stalingrad, had the notion of the hearth and family become a focus fir rhetoric for nationalist and patriotic themes.

The use of personal letters, some of which directed from soldiers to wives back home, were often published along with romantic imagery of the Russian homeland to incite “hatred of the invader,” and “self-sacrifice”.

[41] Deslite the objections of Indian nationalists and the consequences of the war like famine, British propaganda aimed to absolve the blame placed upon Britain.

British propaganda intended to “repress Indian voices in public media” and “regulate social criticism generated by resistant intellectual culture”.

[46] Amongst British propaganda, Indian nationalism in the media expressed the anticolonialist criticisms of Mahatma Gandhi through nationalist reporters like the war correspondent T.G.

[55] Although Germany and Italy were partners in World War II, German propagandists made efforts to influence the Italian press and radio in their favor.

In September 1940, the so-called Dina (Deutsch-italienischer Nachrichten-Austausch) service was set up, ostensibly to improve news exchanges during the war.

In reality, the Dina service served from the beginning to flood Italy with German news material and to control reporting there indirectly.