Bengal famine of 1943

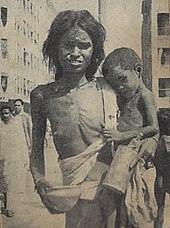

Eventually, families disintegrated; men sold their small farms and left home to look for work or to join the British Indian Army, and women and children became homeless migrants, often travelling to Calcutta or other large cities in search of organised relief.

Stagnant agricultural productivity and a stable land base were unable to cope with a rapidly increasing population, resulting in both long-term decline in per capita availability of rice and growing numbers of the land-poor and landless labourers.

These factors were compounded by restricted access to grain: domestic sources were constrained by emergency inter-provincial trade barriers, while aid from Churchill's war cabinet was limited, ostensibly due to a wartime shortage of shipping.

[89] Throughout this period, transportation of civil supplies was compromised by the railways' increased military obligations, and the dismantling of tracks carried out in areas of eastern Bengal in 1942 to hamper a potential Japanese invasion.

John Herbert, the governor of Bengal, issued an urgent[115] directive in late March 1942 immediately requiring stocks of paddy (unmilled rice) deemed surplus, and other food items, to be removed or destroyed in these districts.

Implemented on 1 May after an initial registration period,[121] the policy authorised the Army to confiscate, relocate or destroy any boats large enough to carry more than ten people, and allowed them to requisition other means of transport such as bicycles, bullock carts, and elephants.

The Indian National Congress, among other groups, staged protests denouncing the denial policies for placing draconian burdens on Bengali peasants; these were part of a nationalist sentiment and outpouring that later peaked in the "Quit India" movement.

[143] As food prices rose and the signs of famine became apparent from July 1942,[144] the Bengal Chamber of Commerce (composed mainly of British-owned firms)[145] devised a Foodstuffs Scheme to provide preferential distribution of goods and services to workers in high-priority war industries, to prevent them from leaving their positions.

[155] The unfavourable military situation of the Allies after the fall of Burma led the US and China to urge the UK to enlist India's full cooperation in the war by negotiating a peaceful transfer of political power to an elected Indian body; this goal was also supported by the Labour Party in Britain.

Winston Churchill, the British prime minister, responded to the new pressure through the Cripps' mission, broaching the post-war possibility of an autonomous political status for India in exchange for its full military support, but negotiations collapsed in early April 1942.

[161][O] In Tamluk, by April 1942 the government had destroyed some 18,000 boats in pursuit of its denial policy, while war-related inflation further alienated the rural population, who became eager volunteers when local Congress recruiters proposed open rebellion.

[227] His requests were again repeatedly denied, causing him to decry the current crisis as "one of the greatest disasters that has befallen any people under British rule, and [the] damage to our reputation both among Indians and foreigners in India is incalculable".

[230] Similarly, Madhusree Mukerjee makes a stark accusation: "The War Cabinet's shipping assignments made in August 1943, shortly after Amery had pleaded for famine relief, show Australian wheat flour travelling to Ceylon, the Middle East, and Southern Africa – everywhere in the Indian Ocean but to India.

"[231] In contrast, Mark Tauger strikes a more supportive stance: "In the Indian Ocean alone from January 1942 to May 1943, the Axis powers sank 230 British and Allied merchant ships totalling 873,000 tons, in other words, a substantial boat every other day.

[241] While some districts of Bengal were relatively less affected throughout the crisis,[242] no demographic or geographic group was completely immune to increased mortality rates caused by disease – but deaths from starvation were confined to the rural poor.

[249] Cholera is a waterborne disease associated with social disruption, poor sanitation, contaminated water, crowded living conditions (as in refugee camps), and a wandering population – problems brought on after the October cyclone and flooding and then continuing through the crisis.

[337] Communists, socialists, wealthy merchants, women's groups, private citizens from distant Karachi and Indian expatriates from as far away as east Africa aided in relief efforts or sent donations of money, food and cloth.

This assistance was delivered promptly, including "a full division of... 15,000 [British] soldiers...military lorries and the Royal Air Force" and distribution to even the most distant rural areas began on a large scale.

[354] Wavell went on to make several other key policy steps, including promising that aid from other provinces would continue to feed the Bengal countryside, setting up a minimum rations scheme,[352] and (after considerable effort) prevailing upon Great Britain to increase international imports.

[356][357][225][146] The famine's aftermath greatly accelerated pre-existing socioeconomic processes leading to poverty and income inequality,[358] severely disrupted important elements of Bengal's economy and social fabric, and ruined millions of families.

Photographs and journalism and the affective bonds of charity tied Indians inextricably to Bengal and made their suffering its own; a provincial [famine] was turned, in the midst of war, into a national case against imperial rule.

[371] Beginning in mid-July 1943 and more so in August, however, these two newspapers began publishing detailed and increasingly critical accounts of the depth and scope of the famine, its impact on society, and the nature of British, Hindu, and Muslim political responses.

[375] Stephens' decision to publish them and to adopt a defiant editorial stance won accolades from many (including the Famine Inquiry Commission),[376] and has been described as "a singular act of journalistic courage without which many more lives would have surely been lost".

(1947) by Bhabani Bhattacharya and the 1980 film Akaler Shandhaney by Mrinal Sen. Ella Sen's collection of stories based on reality, Darkening Days: Being a Narrative of Famine-Stricken Bengal recounts horrific events from a woman's point of view.

Attempting to determine culpability, research and analysis has covered complex issues such as the impacts of natural forces, market failures, failed policies or even malfeasance by governmental institutions, and war profiteering or other unscrupulous acts by private business.

The former see the problem as a series of avoidable war-time policy failures and "panicky responses"[153] from a government that was inept,[401] overwhelmed[402] and in disarray; the latter being a product of wartime priorities by the "ruling colonial elite",[403] which left the poor of Bengal unprovided for, due to military considerations.

[412] Auriol Law-Smith's discussion of contributing causes of the famine also lays blame on the British government of India, primarily emphasising Viceroy Linlithgow's lack of political will to "infringe provincial autonomy" by using his authority to remove interprovincial barriers, which would have ensured the free movement of life-saving grain.

[413] According to 2018 research by Indian economist Utsa Patnaik, the "profit inflation" policies had caused food prices to soar sixfold while wages had remained stagnant, resulting in the widespread starvation and the deaths of three million people.

[437] A final line of blaming holds that major industrialists either caused or at least significantly exacerbated the famine through speculation, war profiteering, hoarding, and corruption – "unscrupulous, heartless grain traders forcing up prices based on false rumors".

Instead they concluded that factors such as wartime inflation, speculative buying, and panic hoarding had severely exacerbated food shortages while Churchill's government had continued exporting rice from India despite warnings of impending famine and denied emergency wheat supplies.