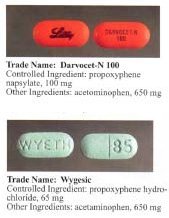

Dextropropoxyphene

Severe toxicity can occur with small increments above the therapeutic dose including cardiotoxicity, and fatal overdoses.

It also acts as a potent, noncompetitive α3β4 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist,[18] as well as a weak serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

[8] Detectable levels of propoxyphene/dextropropoxyphene may stay in a person's system for up to 9 days after last dose and can be tested for specifically in nonstandard urinalysis, but may remain in the body longer in minuscule amounts.

Caution should be used when administering dextropropoxyphene, particularly with children and the elderly and with patients who may be pregnant or breastfeeding; other reported problems include kidney, liver, or respiratory disorders, and prolonged use.

Darvon, a dextropropoxyphene formulation made by Eli Lilly, which had been on the market for 25 years, came under heavy fire in 1978 by consumer groups that said it was associated with suicide.

On November 19, 2010, the FDA announced that Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals agreed to withdraw Darvon and Darvocet in the United States, followed by manufacturers of dextropropoxyphene.

[35] In February 2010, Medsafe announced Paradex and Capadex (forms of dextropropoxyphene) were being withdrawn from the marketplace due to health issues, and withdrawal in other countries.

[37] In Sweden, physicians had long been discouraged by the medical products agency to prescribe dextropropoxyphene due to the risk of respiratory depression and even death when taken with alcohol.

[38] Physicians had earlier been recommended to prescribe products with only dextropropoxyphene and not to patients with a history of substance use disorder, depression, or suicidal tendencies.

This toxicity with the combination of overdosed dextroproxyphene (with its CNS/respiratory depression/vomit with risk for aspiration pneumonia, as well as cardiotoxicity) and paracetamol-induced liver damage can result in death.

[42] From then on in the UK, co-proxamol is only available on a named patient basis, for long-term chronic pain and only to those who have already been prescribed this medicine.

[43] Following the reduction in prescribing in 2005–2007, prior to its complete withdrawal, the number of deaths associated with the drug dropped significantly.

[46] The decision to withdraw co-proxamol has met with some controversy; it has been brought up in the House of Commons on two occasions, 13 July 2005[47] and on 17 January 2007.

[citation needed] During the House of Commons debates, it is quoted that originally some 1,700,000 patients in the UK were prescribed co-proxamol.

[51] In January 2009, an FDA advisory committee voted 14 to 12 against the continued marketing of propoxyphene products, based on its weak pain-killing abilities, addictiveness, association with drug deaths and possible heart problems, including arrhythmia.

A subsequent re-evaluation resulted in a July 2009 recommendation to strengthen the boxed warning for propoxyphene to reflect the risk of overdose.

[52] Dextropropoxyphene subsequently carried a black box warning in the U.S., stating: Propoxyphene should be used with extreme caution, if at all, in patients who have a history of substance/drug/alcohol abuse, depression with suicidal tendency, or who already take medications that cause drowsiness (e.g., antidepressants, muscle relaxants, pain relievers, sedatives, tranquilizers).

[54] On November 19, 2010, the FDA requested manufacturers withdraw propoxyphene from the US market, citing heart arrhythmia in patients who took the drug at typical doses.

[55] Tramadol, which lacks the cardiotoxicity, has been recommended instead of propoxyphene, as it is also indicated for mild to moderate pain, and is less likely to be misused or cause addiction than other opioids.

High toxicity and relatively easy availability made propoxyphene a drug of choice for right-to-die societies.

It is listed in Dr. Philip Nitschke's The Peaceful Pill Handbook and Dr. Pieter Admiraal's Guide to a Humane Self-Chosen Death.