Eric Gill

Although the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography describes Gill as "the greatest artist-craftsman of the twentieth century: a letter-cutter and type designer of genius", he is also a figure of considerable controversy following the revelations of his sexual abuse of two of his daughters and of his pet dog.

At Ditchling, Gill and his assistants created several war memorials including those at Chirk in north Wales and at Trumpington near Cambridge, along with numerous works on religious subjects.

He created engravings for a series of books published by the Golden Cockerel Press considered among the finest of their kind, and it was at Capel that he designed the typefaces Perpetua, Gill Sans, and Solus.

[3][4] In 1900, Gill became disillusioned with Chichester and moved to London to train as an architect with the practice of W. D. Caröe, specialists in ecclesiastical architecture with a large office close to Westminster Abbey.

[1] Frustrated with his architectural training, Gill took evening classes in stonemasonry at the Westminster Technical Institute and, from 1901, in calligraphy at the Central School of Arts and Crafts while continuing to work at Caröe's.

Although by April 1908 Gill had established a workshop in Ditchling and dissolved his business partnership with Lawrence Christie, he continued to spend considerable amounts of time in London visiting clients and delivering lectures, while his wife Ethel organised their household and smallholding in Sussex.

[11] Along with his friend and collaborator Jacob Epstein, Gill planned the construction in the Sussex countryside of a colossal, hand-carved monument in imitation of the large-scale structures at Gwalior Fort in Madhya Pradesh.

[2]: 125 Subsequently, Gill submitted proposals for decorations and works in other parts of the Cathedral building and, eventually, his design for the Chapel of Saint George and the English Martyrs was commissioned.

[16] Gill had been granted exemption from military service while working on the Stations of the Cross and when they were finished spent three months, from September 1918, as a driver at an RAF camp in Dorset, before returning to Ditchling.

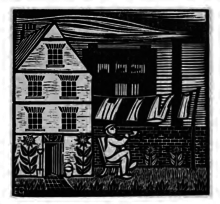

[5] The Press printed books and pamphlets promoting the ideals of the Guilds' traditional craft techniques and also provided an outlet for Gill's engravings and woodcut illustrations.

[1] When approached, in 1924, by Robert Gibbings to produce designs for the Golden Cockerel Press which he and his wife, Moira, had recently acquired, Gill initially refused to work with the couple as they were not Catholics.

[31][a] While living at Capel-y-ffin, Gill spent many weekends at Robert and Moira Gibbings' home in Waltham St Lawrence, enjoying the couple's unconventional and hedonistic lifestyle.

[2]: 191 He was also spending sizable amounts of time in Bristol with a group of young intellectuals centred around Douglas Cleverdon, a bookseller who published and distributed some of Gill's writings.

The work, a giant torso, was modelled by Angela Gill and shown at the Goupil Gallery in London, to considerable acclaim, before being purchased by the artist Eric Kennington.

[2]: 220 [8] It had been too impractical to transport the stone for Mankind to Capel-y-ffin and it was clear that the site had become too remote and isolated for Gill's increasing commercial workload and by May 1928 he was seeking a new home for his family and workshops.

Around a quadrangle with a central pigsty were a large farmhouse housing Eric and Mary Gill, a cottage for Petra and her husband Denis Tegetmeier and another for Joanna and René Hague.

[2]: 228 Gill started on the project within days of arriving at Pigotts and worked on site in London from November 1928 to carve three of eight relief sculptures on the theme of The Four Winds for the building.

He completed The Four Gospels, widely considered to be the finest of all the books produced by the Golden Cockerel Press, and began working on the sculpture Prospero and Ariel for the BBC's Broadcasting House in London.

[2]: 250 During his career, Gill employed at least twenty-seven apprentices including his nephew John Skelton, Hilary Stratton, Desmond Chute, David Kindersley and Donald Potter.

[2]: 275 Gill's original proposal was to create a larger, international, version of the Moneychangers frieze that had caused such outrage in Leeds years earlier, but after objections from delegates to the League, submitted an alternative scheme.

[1] He also worked on a set of panels depicting the stations of the cross for the Anglican St Alban's Church in Oxford, finishing the drawings three weeks before he died and completing nine of the pieces himself.

[1] Gill died of lung cancer in Harefield Hospital in Middlesex on the morning of Sunday 17 November 1940 and, after a funeral mass at the Pigotts chapel, was buried in Speen's Baptist churchyard.

[1] After Gill died an inventory of over 750 of his carved inscriptions was compiled, in addition to the over 100 stone sculptures and reliefs, 1000 engravings, the several typeface designs he created and his 300 printed works including books, articles and pamphlets.

[48] Gill's daughter Petra Tegetmeier, who was alive at the time of the MacCarthy biography, described her father as having "endless curiosity about sex" and that "we just took it for granted", and told her friend Patrick Nuttgens she was unembarrassed.

[48] MacCarthy commented: [A]fter the initial shock, ... as Gill's history of adulteries, incest, and experimental connection with his dog became public knowledge in the late 1980s, the consequent reassessment of his life and art left his artistic reputation strengthened.

Gill emerged as one of the twentieth century's strangest and most original controversialists, a sometimes infuriating, always arresting spokesman for man's continuing need of God in an increasingly materialistic civilization, and for intellectual vigour in an age of encroaching triviality.

[52] In 1998, a group, Ministers and Clergy Sexual Abuse Survivors, called for Gill's Stations of the Cross to be removed from Westminster Cathedral, leading to a debate within the British Catholic press.

[59] When, in 2017, the journalist Rachel Cooke contacted museums holding Gill's work to question what, if any, impact the abuse revelations had on their policy towards showing material by him, the majority refused to engage with her.

Previously, in October 2016, the museum had held a workshop, Not Turning a Blind Eye, with artists, curators and journalists invited to discuss how to address Gill's behaviour in its exhibition programme.

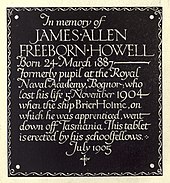

An in-situ example of Gill's design and personal cutting in the style of Perpetua can be found in the nave of the church in Poling, West Sussex, on a wall plaque commemorating the life of Sir Harry Johnston.