Prostitution in ancient Rome

[5] Witzke offers examples from Roman comedies to show that all these terms may be used to refer to the same individual, a hierarchy of politeness, with meretrix the most respectful, but equally used for a brothel slave worker and a high-class free prostitute.

Scortum is an insult in some circumstances but affectionate banter in others, and amica is euphemistic, used in Roman comedies by naive adolescent clients to downplay the commercial basis of their relationship.

A girl (puella, a term used in poetry as a synonym for "girlfriend" or meretrix and not necessarily an age designation) might live with a procuress or madame (lena) or even go into business under the management of her natural mother.

The trope of the "generous whore" goes back to Rome's foundation myth, with Acca Larentia's gift of land to the Roman people, earned during her years as a meretrix.

In 49 BC Cicero was scandalised to find that Pompey, although a married man, allowed his mistress Cytheris, a former slave and actress-turned-courtesan, to occupy the seat of honour reserved for the family materfamilias.

In the context of Augustan poetry, Richard Frank sees Cytheris as an exemplar of the "charming, artistic and educated" women who contributed to a new romantic standard for male–female relationships that Ovid and others articulated in their erotic elegies; a welcome guest for dinner parties at the highest level of Roman society.

[15] One hundred and twenty years later, Suetonius describes an episode in which the emperor Vespasian's mistress, the capable and talented ex-slave and freedwoman Antonia Caenis, offered familial kisses of greeting to his sons.

They could not give evidence in court, and Roman freeborn men and women were forbidden to marry them; as loss of chastity was irreparable, their infamia was a life-long condition.

Other Infames included actors and gladiators, who exerted fascination and sexual allure; and butchers, gravediggers and executioners, polluted by their associations with blood and death.

[19][20] The several Leges Juliae were attempts by rulers of the Julian dynasty to re-establish the social primacy, population levels and dignitas of Rome's ruling classes after the chaos of civil war.

New laws made the Imperial state responsible for matters traditionally managed within citizen families as iures (singular ius, a customary right).

The laws penalised celibacy, promoted marriage and family life, rewarded married couples who produced many children, and punished adultery with degradation and exile.

Any children conceived by a prostitute could never inherit their father's estate, but a convicted and divorced adulteress willing to register and practice as a meretrix could at least partly mitigate her loss of rights, status and income.

As the money was deemed to be polluted, emperor Severus Alexander diverted it from the common state fund towards the upkeep of public buildings, administered by the aediles.

[32] Edwards asserts that the toga, when worn by a meretrix set her apart from respectable women, and suggested her sexual availability;[33] Expensive courtesans wore gaudy garments of see-through silk.

[34] Radicke (2002) claims that most modern interpretations are attempts to rationalise later misunderstandings of primary source material, passed on by Late Antique scholiasts.

[37] A passage from Seneca describes the condition of the prostitute as a slave for sale: Naked she stood on the shore, at the pleasure of the purchaser; every part of her body was examined and felt.

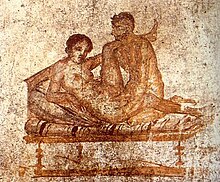

[40] The adjective nudus, however, can also mean "exposed" or stripped of one's outer clothing, and the erotic wall paintings of Pompeii and Herculaneum show women presumed to be prostitutes wearing the Roman equivalent of a bra even while actively engaged in sex acts.

Usually such a brothel is called a lupanar or lupanarium, from lupa, "she-wolf", (slang[48] for a "common prostitute,") or fornix, a general term for a vaulted space or cellar.

The Great Market (macellum magnum) was in this district, along with many cook-shops, stalls, barber shops, the office of the public executioner, and the barracks for foreign soldiers quartered at Rome.

Hair dressers were on hand to repair the ravages wrought by frequent amorous conflicts, and water boys (aquarioli) waited by the door with bowls for washing up.

The licensed houses seem to have been of two kinds: those owned and managed by a pimp (leno) or madam (lena), and those in which the latter was merely an agent, renting rooms and acting as a supplier for his renters.

The cubicle usually contained a lamp of bronze or, in the lower dens, of clay, a pallet or cot of some sort, over which was spread a blanket or patch-work quilt, this latter being sometimes employed as a curtain.

Because intercourse with a meretrix was almost normative for the adolescent male of the period, and permitted for the married man as long as the prostitute was properly registered,[clarification needed][56] brothels were commonly dispersed around Roman cities, often found between houses of respected families.

[61] The poem "The Barmaid" ("Copa"), attributed to Virgil, proves that even the proprietress had two strings to her bow, and Horace,[62] in describing his excursion to Brundisium, narrates his experience with a waitress in an inn.

For, as the mill stones were fixed in places under ground, they set up booths on either side of these chambers and caused prostitutes to stand for hire in them, so that by these means they deceived very many, some that came for bread, others that hastened thither for the base gratification of their wantonness."

Lictors were provided by Rome's senior priest, the pontifex maximus, and were empowered to remove any "impure persons" not merely from the priestess's intended path but from her sight, with violence if need be.

According to Ovid,[71] prostitutes and respectable married women (matronae) shared in the ritual cleansing and reclothing of the cult statue of Fortuna Virilis.

[73] Her festival coincided with the Vinalia, celebrating the "everyday wine" of Venus and the superior, sacred vintage fit for Jupiter and men of the Roman elite.

[72] "Pimped-out boys" (pueri lenonii) were celebrated on 25 April, the same day as the Robigalia, a festival to protect grain crops from fungal infestation.