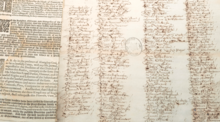

Protestation of 1641

Parliament passed a bill on 3 May 1641 requiring those over the age of 18 to sign the Protestation, an oath of allegiance to King Charles I and the Church of England, as a way to reduce the tensions across the realm.

The Protestation was also a part of a context of political, religious, and social anxiety due to intense changes in a short period in England during the Early Modern era.

Ultimately it failed and tensions continued to escalate between Parliament and King Charles I, eventually leading to the start of the English Civil Wars in August 1642.

However, the Protestation is an enlightening historical phenomenon that help us understand the process that led to the English Civil Wars and attempts that people made to avert a costly conflict, even from those at the center of the hostilities.

Apart from its implications in population census and local historiography, it provides an understanding of how people during the decade of 1640 attempted to avoid a potentially costly and bloody conflict.

Starting in 1517, the Protestant Reformation of Martin Luther began the process of ending the Catholic hegemony in Western faith and its political consequences.

In 1641, amid fears of the Protestant Reformation being in danger of being undone, alleged Papist plots, and Catholic influence under the court of Charles I, the House of Commons during the Long Parliament was ordered by royal decree to prepare a national declaration to help reduce the tensions across England on the matter.

[3] Politically, Charles was forced to end his Personal Rule and call Parliament to raise money for an army to fight the Covenanters in the Second Bishops' War and put revolts in Ireland down.

[5] Charles decided to go on the offensive against the Scottish revolt without Parliament and recalled Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford from Ireland to lead his army in Scotland.

Strafford had successfully controlled the Irish revolt by convincing the Catholic gentry to pay taxes in exchange of future religious benefits, thus increasing the revenue of Charles I and pacifying Ireland.

Once more under the leadership of John Pym, it began to vote on laws that would limit royal power, such as with the prohibition on taxation without Parliamentary consent and the control of Parliament over the King's ministers.

[9] Reacting to scares and anxiety that the Protestant Reformation was in danger of being replaced, especially due to the Catholic influence around King Charles I, a ten-man committee of the House of Commons was selected to draft a national declaration.

Rather than being an instrument against internal conflicts, it fed on them when Speaker Lenthall send the additional letter demanding that all men above 18 years old sign the oath as a response to Charles I's attempt to arrest the Five Members of Parliament.

[15] Following the failure of the 1641 Protestation, the Long Parliament tried two more times to organize an oath of allegiance to King Charles and the Church of England, but they saw the same fate as its predecessor.

Neither party was able to develop the conflicts further at this point, as the Irish, fearing the imposition of Protestantism in their Catholic land rebelled and that country descended into chaos.

On the other, the Parliamentarians or Roundheads were Puritans that wanted to defend what they thought was the traditional form of Church and State that had been unjustly altered by Charles due to ill advice during his 11 years of personal rule.