Gentry

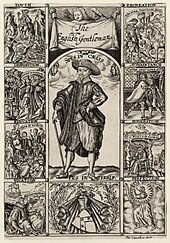

[1][2] Gentry, in its widest connotation, refers to people of good social position connected to landed estates (see manorialism), upper levels of the clergy, or "gentle" families of long descent who in some cases never obtained the official right to bear a coat of arms.

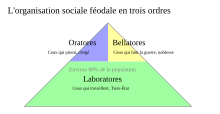

[4][5] The Indo-Europeans who settled Europe, Central and Western Asia and the Indian subcontinent conceived their societies to be ordered (not divided) in a tripartite fashion, the three parts being castes.

The last group, though small in number, monopolized the instruments and opportunities of culture, and ruled with almost unlimited sway half of the most powerful continent on the globe.

The clergy, like Plato's guardians, were placed in authority ... by their talent as shown in ecclesiastical studies and administration, by their disposition to a life of meditation and simplicity, and ... by the influence of their relatives with the powers of state and church.

In the latter half of the period in which they ruled [800 BC onwards], the clergy were as free from family cares as even Plato could desire [for such guardians] ... [Clerical] Celibacy was part of the psychological structure of the power of the clergy; for on the one hand they were unimpeded by the narrowing egoism of the family, and on the other their apparent superiority to the call of the flesh added to the awe in which lay sinners held them.

... Secondly, in spite of numerous examples to the contrary supplied by the warlike Middle Ages, the ecclesiastical calling has by its very nature never been strictly compatible with the bearing of arms.

[11]The fundamental social structure in Europe in the Middle Ages was between the ecclesiastical hierarchy, nobles i.e. the tenants in chivalry (counts, barons, knights, esquires, franklins) and the ignobles, the villeins, citizens, and burgesses.

Subsequent "gentle" families of long descent who never obtained official rights to bear a coat of arms were also admitted to the rural upper-class society: the gentry.

Although there was no formal demarcation between the two categories, the upper clergy were, effectively, clerical nobility, from the families of the second estate or as in the case of Cardinal Wolsey, from more humble backgrounds.

Political power was often in the hands of the landowners in many pre-industrial societies (which was one of the causes of the French Revolution), despite there being no legal barriers to land ownership for other social classes.

Hence, Absolutism was made possible by innovations and characterized as a phenomenon of Early Modern Europe, rather than that of the Middle Ages, where the clergy and nobility counterbalanced as a result of mutual rivalry.

Social division was based on the dominance of the Baltic Germans which formed the upper classes while the majority of indigenous population, called "Undeutsch", composed the peasantry.

In Hungary during the late 19th and early 20th century gentry (sometimes spelled as dzsentri) were nobility without land who often sought employment as civil servants, army officers, or went into politics.

The two historically legally privileged classes in Sweden were the Swedish nobility (Adeln), a rather small group numerically, and the clergy, which were part of the so-called frälse (a classification defined by tax exemptions and representation in the diet).

After compulsory celibacy was abolished in Sweden during the Reformation, the formation of a hereditary priestly class became possible, whereby wealth and clerical positions were frequently inheritable.

Starting from the time of the Reformation, the Latinized form of their birthplace (Laurentius Petri Gothus, from Östergötland) became a common naming practice for the clergy.

This was a period which produced a myriad of two-word Swedish-language family names for the nobility (very favored prefixes were Adler, "eagle"; Ehren – "ära", "honor"; Silfver, "silver"; and Gyllen, "golden").

In the British peerage, only the senior family member (typically the eldest son) inherits a substantive title (duke, marquess, earl, viscount, baron); these are referred to as peers or lords.

is a term derived from the Old French word "escuier" (which also gave equerry) and is in the United Kingdom the second-lowest designation for a nobleman, referring only to males, and used to denote a high but indeterminate social status.

[24] R. H. Tawney had suggested in 1941 that there was a major economic crisis for the nobility in the 16th and 17th centuries, and that the rapidly rising gentry class was demanding a share of power.

The Confucian ideals in the Japanese culture emphasised the importance of productive members of society, so farmers and fishermen were considered of a higher status than merchants.

The small lords, the samurai (武士, bushi), were ordered either to give up their swords and rights and remain on their lands as peasants or to move to the castle cities to become paid retainers of the daimyōs.

In defining how a modern Japan should be, members of the Meiji government decided to follow in the footsteps of the United Kingdom and Germany, basing the country on the concept of noblesse oblige.

Buddhist monks also engaged in record keeping, food storage and distribution, as well as the ability to exercise power by influencing the Goryeo royal court.

Most notables originated in, and belonged to, the fellahin (peasantry) class, forming a lower-echelon land-owning gentry in the Empire's post-Tanzimat countryside and emergent towns.

[34] Rural notables took advantage of changing legal, administrative and political conditions, and global economic realities, to achieve ascendancy using households, marriage alliances and networks of patronage.

A suggestion that a gentleman must have a coat of arms was vigorously advanced by certain 19th- and 20th-century heraldists, notably Arthur Charles Fox-Davies in England and Thomas Innes of Learney in Scotland.

Christianity had a modifying influence on the virtues of chivalry, with limits placed on knights to protect and honour the weaker members of society and maintain peace.

To a degree, gentleman signified a man with an income derived from landed property, a legacy or some other source and was thus independently wealthy and did not need to work.

Like English "small", the word in this context in Chinese can mean petty in mind and heart, narrowly self-interested, greedy, superficial, and materialistic.