Protests of 1968

Incidents The protests of 1968 comprised a worldwide escalation of social conflicts, which were predominantly characterized by the rise of left-wing politics,[1] anti-war sentiment, civil rights urgency, youth counterculture within the silent and baby boomer generations, and popular rebellions against military states and bureaucracies.

In reaction to the Tet Offensive, protests also sparked a broad movement in opposition to the Vietnam War all over the United States as well as in London, Paris, Berlin and Rome.

The most prominent manifestation was the May 1968 protests in France, in which students linked up with wildcat strikes of up to ten million workers, and for a few days, the movement seemed capable of overthrowing the government.

The knowledge that a nuclear warfare could end their life at any moment was reinforced with classroom "duck and cover" bomb drills[5] creating an omnipresent atmosphere of fear.

The Eastern Bloc had already seen several mass protests in the decades following World War II, including the Hungarian Revolution, the uprising in East Germany and several labor strikes in Poland, especially important ones in Poznań in 1956.

In America, the civil rights movement was at its peak, but was also at its most violent, such as the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on 4 April by a white supremacist.

[6] By the time they started college, the majority of young people identified with an anti-establishment culture, which became the impetus for the wave of rebellion and re-imagination that swept through campuses and throughout the world.

Soviet troops were frustrated as street signs were painted over, their water supplies mysteriously shut off, and buildings decorated with flowers, flags, and slogans like, "An elephant cannot swallow a hedgehog."

Road signs in the country-side were over-painted to read, in Russian script, "Москва" (Moscow), as hints for the Soviet troops to leave the country.

The protests that raged throughout 1968 included a large number of workers, students, and poor people facing increasingly violent state repression all around the world.

These refracted into a variety of social causes that reverberated with each other: in the United States alone, for example, protests for civil rights, against nuclear weapons and in opposition to the Vietnam War, and for women's liberation all came together during this year.

As the waves of protests of the 1960s intensified to a new high in 1968, repressive governments through widespread police crackdowns, shootings, executions, and even massacres marked social conflicts in Mexico, Brazil, Spain, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and China.

In West Berlin, Rome, London, Paris, Italy, many American cities, and Argentina, labor unions and students played major roles and also suffered political repression.

[10] In February, students from Harvard, Radcliffe, and Boston University held a four-day hunger strike to protest the Vietnam war.

[12] On 6 March, five hundred New York University (NYU) students demonstrated against Dow Chemical because the company was the principal manufacturer of napalm, used by the U.S. military in Vietnam.

Chicago's mayor, Richard J. Daley, escalated the riots with excessive police presence and by ordering up the National Guard and the army to suppress the protests.

[16] On 7 September, the women's liberation movement gained international recognition when it demonstrated at the annual Miss America beauty pageant.

The aftermath of his death generated one of the first major protests against the military dictatorship in Brazil and incited a national wave of anti-dictatorship student demonstrations throughout the year.

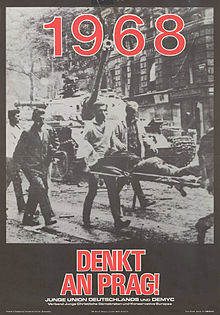

In what became known as Prague Spring, Czechoslovakia's first secretary Alexander Dubček began a period of reform, which gave way to outright civil protest, only ending when the USSR invaded the country in August.

[citation needed] On 1 March, a clash known as the Battle of Valle Giulia took place between students and police in the faculty of architecture in the Sapienza University of Rome.

[19] Protests in Japan, organized by socialist student group Zengakuren, were held against the Vietnam War starting 17 January, coinciding with the visit of the USS Enterprise to Sasebo.

[16] Mexican president Gustavo Díaz Ordaz saw the massive and largely peaceful demonstrations as a threat to Mexico's image on the world stage and to his government's ability to maintain order.

At a televised medal ceremony, black U.S. track stars John Carlos and Tommie Smith each raised one black-gloved hand in the black power salute, and the U.S. Olympic Committee sent them home immediately, albeit only after the International Olympic Community threatened to send the entire track team home if the USOC did not.

[24] Unprecedented class solidarity was displayed and the prejudices of religion, sex, ethnicity, race, nationality, clan or tribe evaporated in the red heat of revolutionary struggle.

[27] On 30 January 300 student protesters from the University of Warsaw and the National Theater School were beaten with clubs by state arranged anti-protestors.

[19] On 3 May activists protested the participation of two apartheid nations, Rhodesia and South Africa, in the international tennis competition held in Båstad, Sweden.

[44] Protests in Yugoslavia, primarily centered at the University of Belgrade, had a significant impact on the political landscape under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito.

Particular grievances focused on the following points: The protests began on 2 June 1968, in Belgrade, following a small clash between students and the police over a canceled theater performance.

These protests revealed the cracks within the Yugoslav socialist system and signaled the difficulties the country would experience in the following decades, leading to its eventual breakup.

Rodney, a historian of Africa, had been active in the Black power movement, and had been sharply critical of the middle class in many Caribbean countries.