Protofeminism

Plato, according to Elaine Hoffman Baruch, "[argued] for the total political and sexual equality of women, advocating that they be members of his highest class... those who rule and fight.

Or do we entrust to the males the entire and exclusive care of the flocks, while we leave the females at home, under the idea that the bearing and suckling their puppies is labour enough for them?

"[7] While in the pre-modern period there was no formal feminist movement in Islamic nations, there were a number of important figures who spoke for improving women's rights and autonomy.

[8] In the 12th century, the Sunni scholar Ibn Asakir wrote that women could study and earn ijazahs in order to transmit religious texts like the hadiths.

In Bidayat al-mujtahid (The Distinguished Jurist's Primer) he added that such duties could include participation in warfare and expressed discontent with the fact that women in his society were typically limited to being mothers and wives.

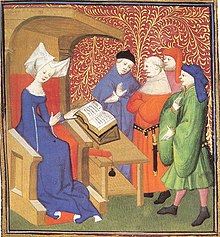

[12] In Christian Medieval Europe, the dominant view was that women were intellectually and morally weaker than men, having been tainted by the original sin of Eve as described in biblical tradition.

The Chief Justice of the King's Bench, Sir John Cavendish, was beheaded by rebels after Katherine Gamen untied the boat he planned on escaping them in.

Ferrour was not the only female leader of the Peasants' Revolt; one Englishwoman was indicted for encouraging an attack on a prison at Maidstone in Kent, and another was responsible for robbing a multitude of mansions, which left servants too scared to return afterwards.

[22] In William Shakespeare's 1593 play The Taming of the Shrew, Katherina is seen as unmarriageable for her headstrong, outspoken nature, unlike her mild sister Bianca.

"[24]Starting with the Malleus Maleficarum, Renaissance Europe saw the publication of numerous treatises on witches: their essence, their features, and ways to spot, prosecute and punish them.

Roger Ascham educated Queen Elizabeth I, who read Latin and Greek and wrote occasional poems such as On Monsieur's Departure that are still anthologized.

A woman named Margherita, living during the Renaissance, learned to read and write at the age of about 30, so there would be no mediator for the letters exchanged between her and her husband.

[29] Although Margherita defied gender roles, she became literate not to become a more enlightened person, but to be a better wife by gaining the ability to communicate with her husband directly.

Cassandra Fedele was the first to join a humanist gentleman's club, declaring that womanhood was a point of pride and equality of the sexes was essential.

[31] Other women including Margaret Roper, Mary Basset and the Cooke sisters gained recognition as scholars by making important translating contributions.

As Protestantism rested on believers' direct interaction with God, the ability to read the Bible and prayer books suddenly became necessary to all, including women and girls.

[35] Some Protestants no longer saw women as weak and evil sinners, but as worthy companions of men needing education to become capable wives.

[38] The figure of the India Juliana has been reclaimed as a foremother by Paraguayan academics and activists as part of a process of "recovery of feminist and women's genealogies" in South America, intended to move away from the Eurocentric vision.

[43] The same has happened in Ecuador with Dolores Cacuango and Tránsito Amaguaña; in the central Andes region with Bartolina Sisa and Micaela Bastidas; and in Argentina with María Remedios del Valle and Juana Azurduy.

[46] While in the convent, she became a controversial figure,[47] advocating recognition of women theologians, criticizing the patriarchal and colonial structures of the Church, and publishing her own writing, in which she set herself as an authority.

Not only did she contribute to the historic discourse of the Querelle des Femmes, but she has also been recognized as a protofeminist, religious feminist, and ecofeminist, and is connected with lesbian feminism.

[50][51][52] This gave prominence to some female ministers and writers such as Mary Mollineux and Barbara Blaugdone in Quakerism's early decades.

In general, though, women who preached or expressed opinions on religion were in danger of being suspected of lunacy or witchcraft, and many, like Anne Askew, who was burned at the stake for heresy,[54] died "for their implicit or explicit challenge to the patriarchal order".

Seventeenth-century France saw the rise of salons – cultural gathering places of the upper-class intelligentsia – which were run by women and in which they took part as artists.

[61] Mary Astell is often described as the first feminist writer, although this ignores the intellectual debt she owed to Anna Maria van Schurman, Bathsua Makin and others who preceded her.

Virginia Woolf praised her: "All women together ought to let flowers fall upon the grave of Aphra Behn... for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.

In Switzerland, the first printed publication by a woman appeared in 1694: in Glaubens-Rechenschafft, Hortensia von Moos argued against the idea that women should stay silent.

[70] In the New World, the Mexican nun, Juana Ines de la Cruz (1651–1695), advanced the education of women in her essay "Reply to Sor Philotea".

Literature in the last decades of the century was sometimes referred to as the "Battle of the Sexes",[72] and was often surprisingly polemic, such as Hannah Woolley's The Gentlewoman's Companion.