History of feminism

[4][15][16][17] Around 24 centuries ago,[18] Plato, according to Elaine Hoffman Baruch, "[argued] for the total political and sexual equality of women, advocating that they be members of his highest class, ... those who rule and fight".

[35][36] Her knowledge was recognized by some, such as proto-feminist Bathsua Makin, who wrote that "The present Dutchess of New-Castle, by her own Genius, rather than any timely Instruction, over-tops many grave Grown-Men," and considered her a prime example of what women could become through education.

[46] In his Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1781), Bentham strongly condemned many countries' common practice to deny women's rights due to allegedly inferior minds.

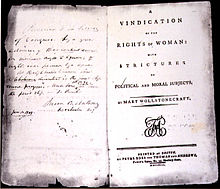

[52] Perhaps the most cited feminist writer of the time was Mary Wollstonecraft, She identified the education and upbringing of women as creating their limited expectations based on a self-image dictated by the typically male perspective.

[72] Starting in 1823[73] and continuing at least as late as 1869,[74] he used magazine articles, short stories, novels, public speaking, political organizing, and personal relationships to advance feminist issues in the United States and Great Britain, reaching the height of his influence in this field circa 1843.

Neal's early feminist essays in the 1820s fill an intellectual gap between Mary Wollstonecraft, Catharine Macaulay, and Judith Sargent Murray and Seneca Falls Convention-era successors like Sarah Moore Grimké, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Margaret Fuller.

Collective concerns began to coalesce by the end of the century, paralleling the emergence of a stiffer social model and code of conduct that Marion Reid described as confining and repressive for women.

[1] While the increased emphasis on feminine virtue partly stirred the call for a woman's movement, the tensions that this role caused for women plagued many early-19th-century feminists with doubt and worry, and fueled opposing views.

[87] The publicity generated from her appeal to Queen Victoria[88] and related activism helped change English laws to recognize and accommodate married women and child custody issues.

[citation needed] Frances Power Cobbe, among others, called for education reform, an issue that gained attention alongside marital and property rights, and domestic violence.

The interrelated barriers to education and employment formed the backbone of 19th-century feminist reform efforts, for instance, as described by Harriet Martineau in her 1859 Edinburgh Journal article, "Female Industry".

Garrett's very successful 1870 campaign to run for London School Board office is another example of a how a small band of very determined women were beginning to reach positions of influence at the local government level.

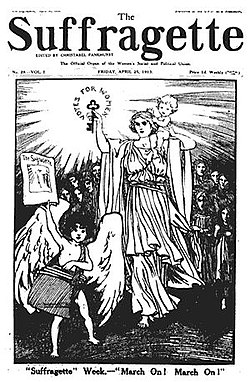

[2] The 19th- and early 20th-century feminist activity in the English-speaking world that sought to win women's suffrage, female education rights, better working conditions, and abolition of gender double standards is known as first-wave feminism.

[112] In 1848 she appeared before an assemblage of men without a veil and gave a speech on the rights of women, signaling a radical break with the prevailing moral order and the start of a new religious and social dispensation.

She delivered her powerful "Ain't I a Woman" speech in an effort to promote women's rights by demonstrating their ability to accomplish tasks that have been traditionally associated with men.

[122] However this attempt to replace androcentric (male-centered) theological[clarification needed] tradition with a gynocentric (female-centered) view made little headway in a women's movement dominated by religious elements; thus she and Gage were largely ignored by subsequent generations.

[citation needed] Feminist scholars like Françoise Thébaud and Nancy F. Cott note a conservative reaction to World War I in some countries, citing a reinforcement of traditional imagery and literature that promotes motherhood.

[159][This quote needs a citation] The 1924 Labour government's social reforms created a formal split, as a splinter group of strict egalitarians formed the Open Door Council in May 1926.

[189] This time was marked by increased female enrolment in higher education, the establishment of academic women's studies courses and departments,[190] and feminist ideology in other related fields, such as politics, sociology, history, and literature.

[191] The rise of the Women's Liberation movement revealed "multiple feminisms", or different underlying feminist lenses, due to the diverse origins from which groups had coalesced and intersected, and the complexity and contentiousness of the issues involved.

Her work has been referred to as "groundbreaking" due to its framing of rape as a social problem; it also had a fair number of critics, primarily from feminists of color, who took issue with Brownmiller's approach to race.

[215] Access to abortion was also widely demanded so as to increase women's economic independence and bodily autonomy, but was more difficult to secure due to existing, deep societal divisions over the issue.

[clarification needed] Examples of such intrafeminism divisions have included disparities between economic development, attitudes towards forms of oppression, the definition of feminism, and stances on homosexuality, female circumcision, and population control.

[citation needed] The Nairobi convention revealed a less monolithic feminism that "constitutes the political expression of the concerns and interests of women from different regions, classes, nationalities, and ethnic backgrounds.

[234] Cochrane identified as fourth wave such organizations and websites as the Everyday Sexism Project and UK Feminista; and events such as Reclaim the Night, One Billion Rising, and "a Lose the Lads' mags protest",[234] where "many of [the leaders] ... are in their teens and 20s".

Niboyet was a Protestant who had adopted Saint-Simonianism, and La Voix attracted other women from that movement, including the seamstress Jeanne Deroin and the primary schoolteacher Pauline Roland.

[246] The Groupe Français d'Etudes Féministes were women intellectuals at the beginning of the 20th century who translated part of Bachofen's canon into French[247] and campaigned for the family law reform.

[249][250][clarification needed] French feminism of the late 20th century is mainly associated with psychoanalytic feminist theory, particularly the work of Luce Irigaray, Julia Kristeva, and Hélène Cixous.

The movement later grew again under feminist figures such as Bibi Khanoom Astarabadi, Touba Azmoudeh, Sediqeh Dowlatabadi, Mohtaram Eskandari, Roshank No'doost, Afaq Parsa, Fakhr ozma Arghoun, Shahnaz Azad, Noor-ol-Hoda Mangeneh, Zandokht Shirazi, Maryam Amid (Mariam Mozayen-ol Sadat).

[265] Japanese feminism as an organized political movement dates back to the early years of the 20th century when Kato Shidzue pushed for birth control availability as part of a broad spectrum of progressive reforms.