Prudence Crandall

In 1832, when Crandall admitted Sarah Harris, a 20-year-old African-American woman, to her school,[2][3] she created what is considered the first integrated classroom in the United States.

Repeated trials for violating a Connecticut law, which was passed to make her work illegal, as well as violence from the townspeople, resulted in Crandall being unable to keep the school open safely.

[2] Much later, the Connecticut legislature, with lobbying from Mark Twain, a resident of Hartford, passed a resolution honoring Crandall and providing her with a pension.

[8]: 9–10 Her teacher there, Rowland Greene, was opposed to slavery, and much later gave an address, published in William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator, on the necessity of education for blacks, and commended Isaac C. Glasgow for sending two of his daughters, "exemplary young women", to Crandall's school for young ladies of color.

[1][10] With the help of her sister and a maid, she taught about forty children in different subjects including geography, history, grammar, arithmetic, reading, and writing.

[4] Although Prudence Crandall grew up as a North American Quaker, she admitted that she was not acquainted with many black people or abolitionists.

After reading The Liberator, Prudence Crandall said in an earlier account that she "contemplated for a while, the manner in which I might best serve the people of color.

Sarah Harris, the daughter of a free African-American farmer near Canterbury,[2] asked to be accepted to the school to prepare for teaching other African Americans.

[12]: 169 [King James translation; the same quotation is on the title page of Charles Crawford's Observations upon Negro-slavery, 1790]She then admitted the girl, establishing the first integrated school in the United States.

(Both were supportive, and gave her letters of introduction to prominent African Americans in locations from Providence, Rhode Island, to New York.)

[4] Crandall announced that on the first Monday of April 1833, she would open a school "for the reception of young Ladies and little Misses of color, ...

[13] As word of the school spread, African-American families began arranging enrollment of their daughters in Crandall's academy.

[8]: 79 In response to the new school, a committee of four prominent white men in the town, Rufus Adams, Daniel Frost Jr., Andrew Harris, and Richard Fenner, attempted to convince Crandall that her school for young women of color would be detrimental to the safety of the white people in the town of Canterbury.

"[2] At first, citizens of Canterbury protested the school and then held town meetings "to devise and adopt such measures as would effectually avert the nuisance, or speedily abate it.

On May 24, 1833, the Connecticut legislature passed a "Black Law", which prohibited a school from teaching African-American students from outside the state without town permission.

[2] Under the Black Law, the townspeople refused any amenities to the students or Crandall, closing their shops and meeting houses to them, although they were welcomed at Prudence's Baptist church, in neighboring Plainfield.

[2] Although she faced extreme difficulties, Crandall continued to teach the young women of color which angered the community even further.

[2] Arthur Tappan of New York, a prominent abolitionist, donated $10,000 to hire the best lawyers to defend Crandall throughout her trials.

But the prosecution's information that charged Crandall had not alleged that she had established her school without the permission of the civil authority and selectmen of Canterbury.

[20][21] On September 9, 1834, a group of townspeople broke almost ninety window glass panes using heavy iron bars.

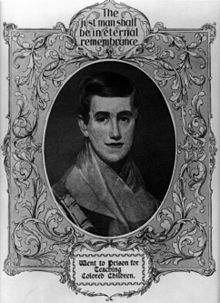

[22] At the suggestion of William Garrison, who raised the money from "various antislavery societies", Francis Alexander painted a portrait of Crandall in April 1834.

[1] The couple moved to Massachusetts for a period of time after they fled the town of Canterbury,[10] and they also lived in New York, Rhode Island, and Illinois.

[4]: 528–529 In 1886, the state of Connecticut honored Prudence Crandall with an act by the legislature, prominently supported by the writer Mark Twain, providing her with a $400 annual pension (equivalent to $13,600 in 2023).

He was no abolitionist and was opposed to Prudence's efforts to educate African-American girls, and told this to her chief enemy Judson, when the latter gave him a ride.

[27] Reuben, who had studied medicine at Yale and practiced for 7 years in Peekskill, New York, was arrested on August 10, 1835, in Washington, D.C., and charged with sedition and publication of abolitionist literature.

It was the first trial for sedition in the history of the country, and being in Washington it attracted a large audience, including members of Congress and reporters.

Over a hundred years later, legal arguments used by her 1834 trial attorneys were submitted to the Supreme Court during their consideration of the historic civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

The remainder of the collection consists of photographs of Crandall, her family members, and their places of residence and Helen Sellers' research materials and correspondence related to her biography.

Went to Jail for Teaching Colored Students.