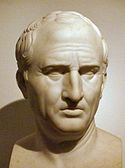

Publius Licinius Crassus (son of triumvir)

Upon his return to Rome, Publius married Cornelia Metella, the intellectually gifted daughter of Metellus Scipio, and began his active political career as a triumvir monetalis and by providing a security force during his father's campaign for a second consulship.

Family meals were simple, and entertaining was generous but not ostentatious; Crassus chose his companions during leisure hours on the basis of personal friendship as well as political utility.

[7] Although the Crassi, as noble plebeians, would have displayed ancestral images in their atrium,[8] they did not lay claim to a fictionalized genealogy that presumed divine or legendary ancestors, a practice not uncommon among the Roman nobility.

[34] Caesar's omission, however, supports the view that the young Crassus held no formal rank, as the Bellum Gallicum consistently identifies officers with regard to their place in the military chain of command.

According to Caesar, the young Crassus, facing a shortage of rations, at some unspecified time sent out detachments to procure grain under the command of prefects and military tribunes, among them four named officers of equestrian status who are seized as hostages by three Gallic polities in collusion.

[69] The situation faced by Publius Crassus in Brittany involved both the prosaic matter of logistics (i.e., feeding the legion under his command)[70] as well as diplomacy among multiple polities, much of which had to be conducted on initiative during Caesar's absence.

The building of a Roman fleet on the river Loire during the winter of 57–56 BC has been interpreted by several modern scholars[71] as preparation for an invasion of Britain, to which the Armoricans would have objected as a threat to their own trade relations with the island.

[72] When he received reports of the hostage situation in Armorica, Caesar had not yet returned to the front from his administrative winter quarters in Ravenna, where he had met with Publius's father for political deal-making prior to the more famous triumviral conference at Luca in April.

The Romans are eventually victorious, but the fate of the hostages is left unstated, and in a break with his policy in working with the Gallic aristocracy over the previous two years, Caesar orders the execution of the entire Venetian senate.

[74] While naval operations were taking place in the waters of the Veneti, Publius Crassus was sent south to Aquitania, this time with a force consisting of twelve Roman legionary cohorts, allied Celtic cavalry and volunteers from Gallia Narbonensis.

On seeing some others who had banded together along with soldiers of Sertorius from Spain and were carrying on the war with skill, and not recklessly, since they believed that the Romans through lack of supplies would soon abandon the country, he pretended to be afraid of them.

The young dux successfully brought the power of war machines to bear in laying siege to a stronghold of the Sotiates; upon surrender, he showed clemency, a quality on which Caesar prided himself, toward the enemy commander Adcantuannus.

[82] Ultimately, Crassus was able to out-general experienced men who had trained in Roman military tactics with the gifted rebel Quintus Sertorius on the Spanish front of the civil wars in the late 80s and 70s BC.

[76] Common among the surviving coins issued by Publius Crassus is a denarius depicting a bust of Venus, perhaps a reference to Caesar's legendary genealogy, and on the reverse an unidentified female figure standing by a horse.

[89] The political value of the marriage for Publius lay in family ties to the so-called optimates, a continually realigning faction of conservative senators who sought to preserve the traditional prerogatives of the aristocratic oligarchy and to prevent exceptional individuals from dominating through direct appeal to the people or the amassing of military power.

Plutarch in particular regards greed as his motive;[97] modern historians tend toward envy and rivalry, since Crassus’ faded military reputation was inferior to that of Pompeius and, after five years of war in Gaul, to that of Caesar.

Elizabeth Rawson, however, suggested that in addition to these or other practical objectives, the war was meant to provide an arena for Publius's abilities as a general, which he had begun to demonstrate so vividly in Gaul.

[98] Cicero implies as much when he enumerates Publius's many fine qualities (see above) and then mourns and criticizes his young friend's destructive desire for gloria: But like many other young men he was carried away by the tide of ambition; and after serving a short time with reputation as a volunteer, nothing could satisfy him but to try his fortune as a general, — an employment which was confined by the wisdom of our ancestors to men who had arrived at a certain age, and who, even then, were obliged to submit their pretensions to the uncertain issue of a public decision.

Thus, by exposing himself to a fatal catastrophe, while he was endeavouring to rival the fame of Cyrus and Alexander, who lived to finish their desperate career, he lost all resemblance of L. Crassus, and his other worthy progenitors.

His thousand cavalry from Celtica (present-day France and Belgium), auxilia provided by technically independent allies, were likely to have been stationed in Cisalpina; it is questionable whether the thousand-strong force he used to pressure elections in January 55 BC were these same men, as the employment of barbarians within Rome should have been viewed as outrageous enough to provoke comment.

Upon entering winter quarters, he spent his time on the 1st-century BC equivalent of number-crunching and wealth management, rather than organizing his troops and engaging in diplomatic efforts to gain allies.

"[102] The military advance was likewise attended by a series of bad omens, and the elder Crassus was frequently at odds with his quaestor, Cassius Longinus, the future assassin of Caesar.

Little is said of any contribution by Publius Crassus until a critical juncture at the river Balissus (Balikh), where most of the officers thought the army ought to make camp, rest after a long march through hostile terrain, and reconnoiter.

Marcus Crassus instead is inspired by the eagerness of Publius and his Celtic cavalry to do battle, and after a quick halt in ranks for refreshment, the army marches headlong into a Parthian trap.

To prevent encirclement, or perhaps in a desperate attempt at diversion,[105] Publius Crassus led out a corps of 1,300 cavalry, primarily his loyal Celtic troopers; 500 archers; and 4,000 elite infantry.

A military historian describes the scene: They soon glimpsed the enemy horsemen only as fleeting shapes through an almost impenetrable curtain of sand and dust thrown up by their myriad hooves, while arrows whistled out of the gloom and pierced shields, mail, flesh and bone.

"[116] Lucan dramatizes the couple's fateful romance to an extreme in his often satiric epic Bellum Civile, where throughout Book 5 Cornelia becomes emblematic of the Late Republic itself, of its greatness and ruin by its most talented men.

The Augustan historian Pompeius Trogus, of the Celtic Vocontii, said that the Parthians feared especially harsh retribution in any war won against them by Caesar, because the surviving son of Crassus would be among the Roman forces.

Several scholars of the 19th and early 20th centuries, including Theodor Mommsen[129] and T. Rice Holmes, thought that this prose work resulted from an expedition during Publius's occupation of Armorica.

[130] Scholars of the 20th and early 21st centuries have been more inclined to assign authorship to the grandfather, during his proconsulship in Spain in the 90s BC, in which case Publius's Armorican mission may have been prompted in part by business interests and a desire to capitalize on the earlier survey of resources.