The History of Rome (Mommsen)

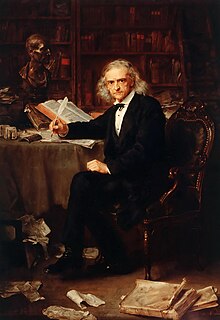

While they certainly wanted a well-respected academic work to fit their acclaimed series on history, Karl Reimer and Solomon Hirzel were also seeking one with literary merit that would be accessible and appeal to the educated public.

Especially in Mommsen's third volume, as the narrative told of how the political crisis in the Roman Republic came to its final climax, "he wrote with a fire of imagination and emotion almost unknown in a professional history.

With rigor Mommsen is shown narrating the grave political drama and illuminating its implications; the book closes with his lengthy description of the new order of government adumbrated by Julius Caesar.

Often strongly worded, he carefully describes the political acts taken by the protagonists, demonstrates the immediate results, draws implications for the future, while shedding light on the evolving society that surround them.

The chronology of the contents of his five 'books' (in his first three volumes) are in brief: The broad strokes of Mommsen's long, sometimes intense narrative of the Roman Republic were summarized at the 1902 award of the Nobel Prize in a speech given by the secretary of the Swedish Academy.

An early source of stability and effectiveness was the stubbornly preserved constitution; e.g., the reformed Senate composed of patricians and plebeians generally handled public affairs of the city-state in an honorable manner.

[34] In the Senate, the old aristocratic oligarchy began to become corrupted by the enormous wealth derived from military conquest and its aftermath;[35] it no longer served well its functional purpose, it failed to meet new demands placed on Rome, and its members would selfishly seek to preserve inherited prerogatives against legitimate challenge and transition.

The free peasantry[37] became squeezed by the competing demands of powerful interests; accordingly its numbers began to dwindle, which eventually led to a restructuring of Army recruitment, and later resulted in disastrous consequences for the entire commonwealth.

[38] Moreover, the annual change of consuls (the two Roman chief executives) began to adversely impact the consistent management of its armed forces, and to weaken their effectiveness, especially in the era following the Punic Wars.

As Rome's strength and reach increased, the political situation developed in which an absolute command structure imposed by military leaders at the top might, in the long run, in many cases be more successful and cause less chaos and hardship to the citizenry than the corrupt and incompetent rule by the oligarchy of quarreling old families who de facto controlled the government.

Eventually the decisive civil war victory of the incomparable Julius Caesar (100–44), followed by his executive mastery and public-minded reforms, appeared as the necessary and welcome step forward toward resolution of the sorry and bloody débâcle at Rome.

Institutions were reformed, the many regions ruled by Rome became more unified in design, as if prepared for a future Empire which would endure for centuries; this, during Caesar's last five and a half years alive.

His work at statecraft included the following: the slow pacification of party strife, nonetheless with republican opposition latent and episodically expressed; his assumption of the title Imperator (refusing the crown, yet continuing since 49 as dictator), with reversion of the Senate to an advisory council, and the popular comitia as a compliant legislature, although law might be made by his edicts alone; his assumption of authority over tax and treasury, over provincial governors, and over the capital; supreme jurisdiction (trial and appellate) over the continuing republican legal system, with the judex being selected among senators or equites, yet criminal courts remained corrupted by factional infighting; supreme command over the decayed Roman army, which was reorganized and which remained under civilian control; reform of government finance, of budgeting re income and expense, and of corn distribution; cultivation of civil peace in Rome by control of criminal "clubs", by new city police, and by public building projects.

A quarter of the way into his short "Introduction" to the Provinces Mommsen comments on the decline of Rome, the capital city: "The Roman state of this epoch resembles a mighty tree, the main stem of which, in the course of its decay, is surrounded by vigorous offshoots pushing their way upward.

[61][62] The following highlights are drawn from Mommsen's renderings of figures of ancient Rome, namely: Hannibal, Scipio Africanus, the Gracchi brothers, Marius, Drusus, Sulla, Pompey, Cato, Caesar, and Cicero.

[88][89] "[T]hrough comparative linguistics, numismatics, and epigraphy, Mommsen was trying to create a body of material which had the status of archival evidence and which would serve as a control on the narratives of historical writers such as Livy and Appian.

"[The book] astonished and shocked professional scholars by its revolutionary treatment of the misty beginnings of Rome, sweeping away the old legends of the kings and heroes and along with them the elaborate critical structure deduced from those tales by Barthold Niebuhr, whose reputation as the grand master of Roman history was then sacrosanct.

As an organism is better than a machine "so is every imperfect constitution which gives room for the free self-determination of a majority of citizens infinitely [better] than the most humane and wonderful absolutism; for one is living, and the other is dead."

They readily admit that the Senate was dominated by a hardcore of 'aristocrats' or the 'oligarchy', who also nearly monopolized the chief offices of government, e.g., consul, by means of family connection, marriage alliance, wealth, or corruption.

In fact when Mommsen wrote his Römische Geschichte (1854–1856) political parties in Europe and America were also generally amorphous, being comparatively unorganized and unfocused, absent member allegiance and often lacking programs.

[102] Accordingly, Carr informs us that Mommsen's multivolume work Römische Geschichte (Leipzig 1854–1856) may tell the perceptive modern historian much about mid-19th-century Germany, while it is presenting an account of ancient Rome.

[103][104][105] A major recent event in Germany was the failure of the 1848–1849 Revolution, while in Mommsen's Roman History his narration of the Republic draws to a close with the revolutionary emergence of a strong state executive in the figure of Julius Caesar.

"Grote, an enlightened radical banker writing in the 1840s, embodied the aspirations of the rising and politically progressive British middle class in an idealized picture of Athenian democracy, in which Pericles figured as a Benthamite reformer, and Athens acquired an empire in a fit of absence of mind.

[109]"I should not think it an outrageous paradox", writes Carr, "if someone were to say that Grote's History of Greece has quite as much to tell us about the thought of the English philosophical radicals in the 1840s as about Athenian democracy in the fifth century B.C.

[117] Caesar was opposed by an oligarchy of aristocratic families, the optimates, who dominated the Senate and nearly monopolized state offices, who profited by the city's corruption and exploited the foreign conquests.

Hence Caesar's career was associated with the struggle for a new order and, failing opportunity along peaceful avenues, he emerged as a military leader whose triumph at arms worked to advance political change.

"[135]A modern historian of ancient Rome echoes the rough, current consensus of academics about this great and controversial figure, as he concludes his well-regarded biography of Julius Caesar: "When they killed him his assassins did not realise that they had eliminated the best and most far-sighted mind of their class.

As to the matter of why "Mommsen failed to continue his history beyond the fall of the republic", Carr wrote: "During his active career, the problem of what happened once the strong man had taken over was not yet actual.

"[145] G. P. Gooch gives us these comments evaluating Mommsen's History: "Its sureness of touch, its many-sided knowledge, its throbbing vitality and the Venetian colouring of its portraits left an ineffaceable impression on every reader."

"[152] The British historian G. P. Gooch, writing in 1913, eleven years after Mommsen's Nobel prize, gives us this evaluation of his Römisches Geschichte: "Its sureness of touch, its many-sided knowledge, its throbbing vitality and the Venetian colouring of its portraits left an ineffaceable impression on every reader."