Pueblo pottery

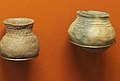

Some utility wares were undecorated except from simple corrugations or marks made with a stick or fingernail, however many examples for centuries were painted with abstract or representational motifs.

[7] In the 20th century, pueblo pottery entered the commercial marketplace with its primarily Anglo "middle-men" of gallerists and independent dealers acting as representatives for the artists, who sold these wares to museums and private collectors.

[2] This drove up the value of modern and contemporary works, and created a black market for historic and prehistoric objects; even prominent galleries in the 1990s were selling pueblo pottery of questionable provenance.

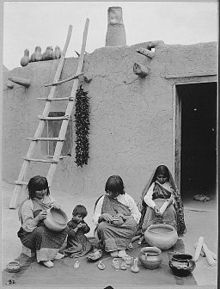

The clay is then worked using coiling techniques to form it into vessels that are primarily used for utilitarian purposes such as pots, storage containers for food and water, bowls and platters.

[18] Fired pottery is thought to have come to the Southwest by two main vectors: a route along the west coast of Mexico adjacent to the Gulf of California, and entering the area that is now Arizona.

The Tewa potters at this time covered their vessels in cream-colored slip, and painted designs in black glaze, producing pottery with a finer, more precise line quality.

Some archaeologists have proposed that the production range of Red Mesa ware was limited to Chaco Canyon and was distributed to or traded with people in outlying areas where the influence of Chaco-style architecture was also seen.

[1][26] Use of mineral pigments made of copper, iron and manganese began in about AD 1050–1200 as far north as the San Juan Basin and as far south as Zuni and the Cibola provinces.

This led potters especially at Santa Clara and San Ildefonso pueblos to experiment with dung-smothered reduction-fired blackware techniques that were further refined in the early 20th century.

The slipped areas could be burnished into a fine polish, however this coating was sometimes fugitive and would flake off during the firing, the potters learned to selectively paint designs on their pots.

Archaeologists have determined that the blackened interiors were produced by reduction-firing (reducing the oxygen during the firing process)—this transformed the hematite in clay into black magnetite.

Very large bowls have been found, dated to around AD 1350, which are thought, by archeologists to be used for feasting; as they are completely absent in any burial sites, therefore evidence points to the former purpose.

[34] Jeddito yellow ware is a type of pottery specific to the Hopi Pueblo and its outlying villages in Northern Arizona, although it was traded with the Navajo and the Puebloan people of New Mexico.

The reason for its unique yellow color is due to the type of low-iron local clay and of even more importance, that starting in about AD 1300, the Hopi fired their pottery with coal rather than wood or dung.

Carlson and others have proposed that potters who lived in the area where Durango, Colorado now exists accidentally developed a pigment from a mineral containing lead that produced a blue-black, greenish-black or maroon glaze.

A Pueblo III Era site on private land, known as Indian Camp Ranch subdivision, in southwest Colorado near Mesa Verde, is sold in lot parcels where wealthy, mostly white buyers can build a home and also excavate their property for artifacts.

Tilly wrote extensively on the Zuni, and while she was a role model for women in the sciences, especially anthropology, she arranged for thousands of objects to be mysteriously transferred to the East Coast.

[47] In a 2005 sting operation 100 federal agents stormed eight homes in Blanding, Utah, to arrest 32 non-Native people and recover thousands of artifacts mostly looted from the Four Corners region.

[9] Forest Cuch, a Ute tribal member and then-director of the Utah Division of Indian Affairs has said that looting "is a dehumanization of native culture by ignorant people.

""[48] The native New Mexican Norman Nelson, who is a second-generation archaeologist estimates that 95% of sites have been looted, and that prehistoric Mimbres black-on-white style pottery fetches high prices on the market, particularly to collectors in "Scandinavia, Sweden, Germany, Japan and China."

[8] The archaeologist, Phil Young, who is also a retired special agent for the National Park Service recalls the 1990s when a series of prominent galleries in Santa Fe that were selling illegally obtained objects.

"[49] In several museum collections across the country there are a distinctive group of ceramic objects that came from Laguna Pueblo in west central New Mexico,[3] all of them were produced between 1890 and 1920, and they seem to have been made by the same artist.

Acoma Pueblo pottery was long appreciated for its bright white slipped, thin-walled vessels and abstract fine line and checker-board geometric ornamentation.

Artists from Santo Domingo Pueblo (between Albuquerque to the south and Santa Fe to the north) also use floral and bird motifs along with geometric lines and patterns, usually in red.

Zuni artists in the far west-central New Mexico began ornamenting their pottery in the 20th century with dragonflies, deer, owls and frogs, and floral patterns inspired by the Spanish influence.

[53] Many contemporary Pueblo artists seek to transcend the anthropological and ethnographic interpretations of their work, or stereotypes of how Native ceramic art should "look" or what its conceptual framework should be.

This diversity of approaches ruptures any lingering Eurocentric or academic notions of what constitutes modernism, and blows down these walls to reveal the complexities of Indigeneity in the postmodern art world.

Peter Held has written that these contemporary Native ceramic artists have become "transdisciplinary producers of knowledge" and that: "(t)hese shifting paradigms are manifestations of social, political, technological, economic, ecological and cultural conditions.

'"[59] Simultaneously, Comanche art critic, Paul Chaat Smith has suggested that this culture trap is an "ideological prison" that is "capable of becoming an elixir that [we] Indian people ourselves find irresistible."

[60][61] Rose Bean Simpson, another Santa Clara artist who frequently works in ceramics, believes art can bring about systemic changes by "building awareness around the energy of colonization, around Indigenous culture, bodies, and place", and alleviate "Post Colonial Stress Disorder.