Relative density

Specific gravity for solids and liquids is nearly always measured with respect to water at its densest (at 4 °C or 39.2 °F); for gases, the reference is air at room temperature (20 °C or 68 °F).

[4] Specific gravity is commonly used in industry as a simple means of obtaining information about the concentration of solutions of various materials such as brines, must weight (syrups, juices, honeys, brewers wort, must, etc.)

For example, one mol of an ideal gas occupies 22.414 L at 0 °C and 1 atmosphere whereas carbon dioxide has a molar volume of 22.259 L under those same conditions.

The apparent specific gravity is simply the ratio of the weights of equal volumes of sample and water in air:

Measurements are nearly always made at 1 nominal atmosphere (101.325 kPa ± variations from changing weather patterns), but as specific gravity usually refers to highly incompressible aqueous solutions or other incompressible substances (such as petroleum products), variations in density caused by pressure are usually neglected at least where apparent specific gravity is being measured.

As the principal use of specific gravity measurements in industry is determination of the concentrations of substances in aqueous solutions and as these are found in tables of SG versus concentration, it is extremely important that the analyst enter the table with the correct form of specific gravity.

In the sugar, soft drink, honey, fruit juice and related industries, sucrose concentration by weight is taken from a table prepared by A. Brix, which uses SG (17.5 °C/17.5 °C).

As the principal use of relative density measurements in industry is determination of the concentrations of substances in aqueous solutions and these are found in tables of RD vs concentration it is extremely important that the analyst enter the table with the correct form of relative density.

In the sugar, soft drink, honey, fruit juice and related industries sucrose concentration by mass is taken from this work[4] which uses SG (17.5 °C/17.5 °C).

It is used in automated compounders in preparation of multicomponent mixtures for parenteral nutrition, while it is an important factor in urinalysis, relative density is an indicator of both the concentration of particles in the urine and a patient's degree of hydration.

{\displaystyle \rho ={\frac {\text{Mass}}{\text{Volume}}}={\frac {{\text{Deflection}}\times {\frac {\text{Spring Constant}}{\text{Gravity}}}}{{\text{Displacement}}_{\mathrm {WaterLine} }\times {\text{Area}}_{\mathrm {Cylinder} }}}.}

When these densities are divided, references to the spring constant, gravity and cross-sectional area simply cancel, leaving

The relative density result is the dry sample weight divided by that of the displaced water.

A sample less dense than water can also be handled, but it has to be held down, and the error introduced by the fixing material must be considered.

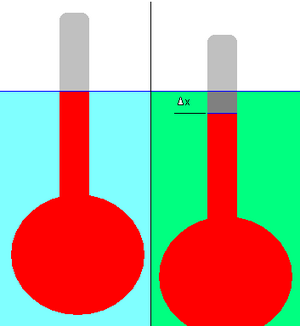

This consists of a bulb attached to a stalk of constant cross-sectional area, as shown in the adjacent diagram.

The application of simple physical principles allows the relative density of the unknown liquid to be calculated from the change in displacement.

or just Exactly the same equation applies when the hydrometer is floating in the liquid being measured, except that the new volume is V − AΔx (see note above about the sign of Δx).

This device enables a liquid's density to be measured accurately by reference to an appropriate working fluid, such as water or mercury, using an analytical balance.

When a pycnometer is filled to a specific, but not necessarily accurately known volume, V and is placed upon a balance, it will exert a force

ρa is the density of the air at the ambient pressure and ρb is the density of the material of which the bottle is made (usually glass) so that the second term is the mass of air displaced by the glass of the bottle whose weight, by Archimedes Principle must be subtracted.

Where the relative density of the sample is close to that of water (for example dilute ethanol solutions) the correction is even smaller.

Types Hydrostatic Pressure-based Instruments: This technology relies upon Pascal's Principle which states that the pressure difference between two points within a vertical column of fluid is dependent upon the vertical distance between the two points, the density of the fluid and the gravitational force.

This technology is often used for tank gauging applications as a convenient means of liquid level and density measure.

In modern laboratories precise measurements of relative density are made using oscillating U-tube meters.

These are capable of measurement to 5 to 6 places beyond the decimal point and are used in the brewing, distilling, pharmaceutical, petroleum and other industries.

The instruments measure the actual mass of fluid contained in a fixed volume at temperatures between 0 and 80 °C but as they are microprocessor based can calculate apparent or true relative density and contain tables relating these to the strengths of common acids, sugar solutions, etc.

Radiation-based Gauge: Radiation is passed from a source, through the fluid of interest, and into a scintillation detector, or counter.

A key advantage for this technology is that the instrument is not required to be in contact with the fluid—typically the source and detector are mounted on the outside of tanks or piping.

When the head is immersed vertically in the liquid, the float moves vertically and the position of the float controls the position of a permanent magnet whose displacement is sensed by a concentric array of Hall-effect linear displacement sensors.

[15] Errors can also occur due to impurities, incomplete mixing, or air bubbles in liquids, which can skew results.