Qajar art

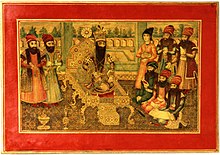

The boom in artistic expression that occurred during the Qajar era was a side effect of the period of relative peace that accompanied the rule of Agha Mohammad Khan and his descendants.

This is especially evident in the portrayal of Qajar royalty, where the subjects of the paintings are very formulaically placed and situated to achieve a desired effect.

The most famous of these are the myriad portraits which were painted of Fath Ali Shah Qajar, who, with his narrow waist, long black bifurcated beard and deepest dark eyes, has come to exemplify the Romantic image of the great Oriental Ruler.

In the latter category, Qajar rulers like Fath ‘Ali Shah (r. 1797–1834) perpetuated a widespread interest in large-scale portraiture (even sending portraits to political rivals).

"[1] While Fath Ali Shah himself never visited Europe, many portraits of him were sent with envoys in the effort to convey the imperial majesty of the Qajar court.

During the reign of Naser ad-Din Shah photography became much more important, and portraiture, while still used for official purposes, fell gradually out of favor.

In addition, as Naser ad-Din Shah was the first Iranian monarch to visit Europe, the official sending of portraits was left by the wayside, a relic of times gone by.

One way that this was accomplished was through a cartouche that was displayed next to the head of each portrait's subject, clarifying who was being depicted, and any relevant titles (such as Soltān, shāhzādeh, &c.).

For the ruling head of Iran, this cartouche is fairly regulated, ("al-soltān Official name Shāh Qājār"), while for anyone else, it may include a longer name, a lesser title or a short genealogy.

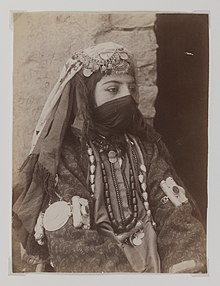

Likewise, Mongol women, due to their nomad lifestyle, were conditioned to lead a physically active life, making heavy veiling unpractical.

Consequently, due to the influences of Mongols and expanding ties with Europe, where Italian renaissance was at its peak, Iranian artists rethought their attitude towards the painting of women.

[4] It was not until the 19th century when females were depicted as more individualized with distinct feminine facial and body features which ultimately led to the disappearance of the mukhanna, the male object of desire.

This was interpreted as a rejection to a social order which is represented in folk narratives in both pictorial and literary representations to dismiss the stereotype of passive Iranian women.

Due to social, cultural, and religious constraints, art samples created by women were rarely preserved, since society, in general, didn't encourage female self-expression.

Harem represented a femicentric space, where women were able to freely exchange and share ideas, not influenced by hierarchal submission to men in 19th-century Iran, experiencing levels of autonomy.

During the reign of Fath Ali Shah Qajar, a work of literature and art was commissioned that was intended to rival the Shāhnāmeh (شاهنامه, lit.

Art historian Pamela Karimi also notes that some women from shah's harem were depicted unveiled and “in erotic poses”.

[15] Jane Dieulafoy (1851-1916), Isabella Lucy Bishop-Bird (1868-1926), and Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell (1869-1926) are three western female travelers in Iran during the Qajar era, who were active in photographing both men, women, and social groups.

Bird, in her turn, was less interested in depicting women, whereas, in her travelogue Journeys in Persian and Kurdistan on Horseback in 1890, she writes about female daily life and culture in Iran.

Gertrude Bell, traveling through Iran in 1911, motivated by archaeological research, was rather concentrated on depicting Iranian landscapes and nature sites, rather than women.

[15] In 1858, male French photographer Frances Carhlian was appointed by the court to teach photography, propagating the collodion method in the state.

As for the Iranian photographers except for shah, only members of nobility had an opportunity to develop in photography, since such a hobby required high expenses, inaccessible to all layers of society.

Dust Mohammed Khan Mo’ayyer-ol-Mamalek (1856–1912), husband of one of the shah's daughters, together with his brother Mirza, established a photo studio in their house.

From the only accessible sources, it is assumed that women from upper-class families and wives of photographers had the greatest opportunity to acquire the skill professionally.

As Naomi Rosenblum concluded, after helping the husband in the photo business, a wife herself would frequently continue with it, after her spouse would pass away.

Comparatively major holdings of Iranian literature heritage are mainly held in Iran, but also Russian, English, German and French libraries; and in personal collections.

[17] A period of Qajar rule was characterized by a move from neoclassic literary tradition inherent of conservative Islamic society to reformist aesthetics of pre-constitutional revolution.