Qarmatian invasion of Iraq

Nevertheless, the invasion of 927–928 severely deteriorated the financial and political situation in the Abbasid Caliphate, which descended into a vicious circle of military coups and internecine warfare among warlords, culminating in 946 with the takeover of Iraq by the Buyid dynasty.

[3] In 899, the Isma'ili movement split between a branch that followed the leadership of the future Fatimid caliph, Abdallah al-Mahdi, and those who rejected his claims to the imamate, known as the "Qarmatians".

[15] Despite the alarming sack of Basra, Ibn al-Furat was more concerned with securing his own position than making military preparations; indeed, to remove his most powerful rival from Baghdad, he sent the commander-in-chief, Mu'nis al-Muzaffar, with his army to Raqqa, in virtual exile.

[12][17] As pro-Shi'a sympathizers flocked to Bahrayn, the Abbasid government, divided by factional rivalries and incapacitated by lack of funds, failed to respond effectively to the Qarmatian threat.

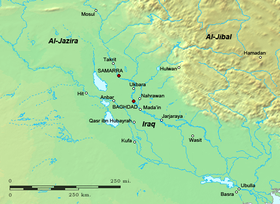

[20] The Hajj caravan of the next year was attacked on its way to Mecca, and despite an escort of 6,000 men had to turn back to Kufa pursued by the Qarmatians, taking heavy losses.

[18][22] In the next Hajj season, in January 926, a strong military escort ensured the safety of the pilgrims, but the authorities nevertheless paid a hefty sum to the Qarmatians to be allowed through.

During the following Hajj, the caravan had to be called off entirely as the Abbasid government lacked the funds to provide the escort, and panic spread in Mecca as its inhabitants deserted the city in anticipation of a Qarmatian attack that never came.

[18] In the meantime, the Abbasid government made frantic efforts to gather money for recruiting more soldiers, but the two short-lived viziers who followed Ibn al-Furat, Abdallah al-Khaqani and Ahmad al-Khasibi, were unable to shore up the state's finances.

[23] Matters were made worse by persistent rumours that elements in the Abbasid government were secretly in league with the Qarmatians, a charge that was liberally levelled at political opponents at the time.

[23] In desperation, in 926 the vizier al-Khasibi called upon the semi-autonomous, hereditary Sajid emir of Adharbayjan and Armenia, Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj, with his troops, to confront the Qarmatian menace.

As the treasury was empty, the revenues of the eastern provinces still under Abbasid control (the Jibal and northwestern Persia), along with Ibn Abi'l-Saj's own domains, were allocated for the upkeep of his army.

[1] Finally, in April 927, Ali ibn Isa was recalled to the vizierate at the insistence of Mu'nis, to lead a sort of 'national unity government' to deal with the crisis.

[1] Mu'nis was recalled from a campaign against the Byzantine Empire, large stores of weapons and supplies set up at Kufa, and Ibn Abi'l-Saj ordered to make for the city.

[31][34] As Kennedy remarks, the Abbasid government's policy of concentrating its troops in the capital meant that cities across the Caliphate were left to their own devices, forced to hastily improvise defences and raise militias to fend off the attackers.

They massacred the Hajj pilgrims, desecrated the Zamzam Well by throwing in corpses and plundered the Kaaba, taking its relics, including the Black Stone, with them to their capital al-Ahsa.

[41] In the event, the bizarre and autocratic behaviour of the supposed Mahdi, who was worshipped as a living god and had several leading Qarmatians executed, aroused resistance, and he was murdered soon after.

[42] Abu Tahir was able to retain power over Bahrayn, and the Qarmatian leadership denounced the entire episode as an error and reverted to its previous adherence to Islamic law.

[43][44] Nevertheless, the affair of the false Mahdi tarnished the prestige of Abu Tahir and shattered the morale of the Qarmatians, many of whom abandoned Bahrayn to seek service in the armies of various regional warlords.

[43] At the same time, the event evidently checked Abu Tahir's ambitions: after conquering Oman in 930, he seemed poised to repeat his invasion of Iraq, but after a sack of Kufa in 931, he returned with his men back to Bahrayn to deal with the false Mahdi.

[45] Over the following years, the Qarmatians of Bahrayn entered into negotiations with the Abbasid government, resulting in the conclusion of a peace treaty in 939, and eventually the return of the Black Stone to Mecca in 951.