Quagga

They were once found in great numbers in the Karoo of Cape Province and the southern part of the Orange Free State in South Africa.

After the European settlement of South Africa began, the quagga was extensively hunted, as it competed with domesticated animals for forage.

The extant northern population, the "Damara zebra", was later named Equus quagga antiquorum, which means that it is today also referred to as E. q. burchellii, after it was realised they were the same taxon.

[11] Different subspecies of plains zebras were recognised as members of Equus quagga by early researchers, though much confusion existed over which species were valid.

Studying skeletons from stuffed specimens can be problematical, as early taxidermists sometimes used donkey and horse skulls inside their mounts when the originals were unavailable.

[5] Fossil skulls of Equus mauritanicus from Algeria have been claimed to show affinities with the quagga and the plains zebra, but they may be too badly damaged to allow definite conclusions to be drawn from them.

[19] A 1987 study suggested that the mtDNA of the quagga diverged at a range of roughly 2 percent per million years, similar to other mammal species, and again confirmed the close relation to the plains zebra.

It showed that the quagga had little genetic diversity, and that it diverged from the other plains zebra subspecies only between 120,000 and 290,000 years ago, during the Pleistocene, and possibly the penultimate glacial maximum.

They found no evidence for subspecific differentiation based on morphological differences between southern populations of zebras, including the quagga.

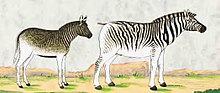

[23] On the basis of photographs and written descriptions, many observers suggest that the stripes on the quagga were light on a dark background, unlike other zebras.

The German naturalist Reinhold Rau, pioneer of the Quagga Project, claimed that this is an optical illusion: that the base colour is a creamy white and that the stripes are thick and dark.

[11] Living in the very southern end of the plains zebra's range, the quagga had a thick winter coat that moulted each year.

[9] The 2004 morphological study found that the skeletal features of the southern Burchell's zebra population and the quagga overlapped, and that they were impossible to distinguish.

Today, some stuffed specimens of quaggas and southern Burchell's zebra are so similar that they are impossible to definitely identify as either, since no location data was recorded.

[11] The only source that unequivocally describes the quagga in the Free State is that of the British military engineer and hunter William Cornwallis Harris.

Beyond, on those sultry plains which are completely taken possession of by wild beasts, and may with strict propriety be termed the domains of savage nature, it occurs in interminable herds; and, although never intermixing with its more elegant congeners, it is almost invariably to be found ranging with the white-tailed gnu and with the ostrich, for the society of which bird especially it evinces the most singular predilection.

Moving slowly across the profile of the ocean-like horizon, uttering a shrill, barking neigh, of which its name forms a correct imitation, long files of quaggas continually remind the early traveller of a rival caravan on its march.

[29] A 2014 study strongly supported the biting-fly hypothesis, and the quagga appears to have lived in areas with lesser amounts of fly activity than other zebras.

[30] A 2020 study suggested that the sexual dimorphism in size, with quagga mares being larger than stallions, could be due to the cold and droughts that affects the Karoo plateau, conditions that were even more severe in prehistoric times, such as during ice ages (other plains zebras live in warmer areas).

[31] As it was easy to find and kill, the quagga was hunted by early Dutch settlers and later by Afrikaners to provide meat or for their skins.

[34][35] In 1843, the English naturalist Charles Hamilton Smith wrote that the quagga was 'unquestionably best calculated for domestication, both as regards strength and docility'.

[36][37] In an attempt at domesticating the quagga, the British lord George Douglas, 16th Earl of Morton obtained a single male which he bred with a female horse of partial Arabian ancestry.

[25] At the close of the 19th century, the Scottish zoologist James Cossar Ewart argued against these ideas and proved, with several cross-breeding experiments, that zebra stripes could appear as an atavistic trait at any time.

The last captive quagga, a female in Amsterdam's Natura Artis Magistra zoo, lived there from 9 May 1867 until it died on 12 August 1883, but its origin and cause of death are unclear.

[13] Its death was not recognised as signifying the extinction of its kind at the time, and the zoo requested another specimen; hunters believed it could still be found "closer to the interior" in the Cape Colony.

[45] In 1889, the naturalist Henry Bryden wrote: "That an animal so beautiful, so capable of domestication and use, and to be found not long since in so great abundance, should have been allowed to be swept from the face of the earth, is surely a disgrace to our latter-day civilization.

[25] The founding population consisted of 19 individuals from Namibia and South Africa, chosen because they had reduced striping on the rear body and legs.

[16][47] Introduction of these quagga-like zebras could be part of a comprehensive restoration programme, including such ongoing efforts as eradication of non-native trees.

Quaggas, wildebeest, and ostriches, which occurred together during historical times in a mutually beneficial association, could be kept together in areas where the indigenous vegetation has to be maintained by grazing.