Evolution of the horse

The horse belongs to the order Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates), the members of which all share hooved feet and an odd number of toes on each foot, as well as mobile upper lips and a similar tooth structure.

On 10 October 1833, at Santa Fe, Argentina, he was "filled with astonishment" when he found a horse's tooth in the same stratum as fossil giant armadillos, and wondered if it might have been washed down from a later layer, but concluded this was "not very probable".

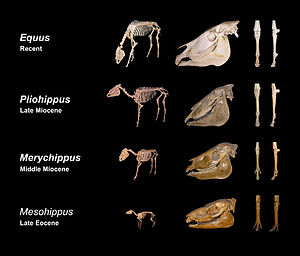

[9] The original sequence of species believed to have evolved into the horse was based on fossils discovered in North America in 1879 by paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh.

The sequence, from Eohippus to the modern horse (Equus), was popularized by Thomas Huxley and became one of the most widely known examples of a clear evolutionary progression.

Since then, as the number of equid fossils has increased, the actual evolutionary progression from Eohippus to Equus has been discovered to be much more complex and multibranched than was initially supposed.

Although some transitions, such as that of Dinohippus to Equus, were indeed gradual progressions, a number of others, such as that of Epihippus to Mesohippus, were relatively abrupt in geologic time, taking place over only a few million years.

The family lived from the Early Paleocene to the Middle Eocene in Europe and were about the size of a sheep, with tails making slightly less than half of the length of their bodies and, unlike their ancestors, good running skills.

It was an animal approximately the size of a fox (250–450 mm in height), with a relatively short head and neck and a springy, arched back.

Thousands of complete, fossilized skeletons of these animals have been found in the Eocene layers of North American strata, mainly in the Wind River basin in Wyoming.

[14] Approximately 50 million years ago, in the early-to-middle Eocene, Eohippus smoothly transitioned into Orohippus through a gradual series of changes.

In the mid-Eocene, about 47 million years ago, Epihippus, a genus which continued the evolutionary trend of increasingly efficient grinding teeth, evolved from Orohippus.

In the late Eocene and the early stages of the Oligocene epoch (32–24 mya), the climate of North America became drier, and the earliest grasses began to evolve.

[17] The forest-suited form was Kalobatippus (or Miohippus intermedius, depending on whether it was a new genus or species), whose second and fourth front toes were long, well-suited to travel on the soft forest floors.

[20] The Miohippus population that remained on the steppes is believed to be ancestral to Parahippus, a North American animal about the size of a small pony, with a prolonged skull and a facial structure resembling the horses of today.

The hind legs, which were relatively short, had side toes equipped with small hooves, but they probably only touched the ground when running.

The most different from Merychippus was Hipparion, mainly in the structure of tooth enamel: in comparison with other Equidae, the inside, or tongue side, had a completely isolated parapet.

In North America, Hipparion and its relatives (Cormohipparion, Nannippus, Neohipparion, and Pseudhipparion), proliferated into many kinds of equids, at least one of which managed to migrate to Asia and Europe during the Miocene epoch.

[26] Molecular phylogenies indicate the most recent common ancestor of all modern equids (members of the genus Equus) lived ~5.6 (3.9–7.8) mya.

[27] The oldest divergencies are the Asian hemiones (subgenus E. (Asinus), including the kulan, onager, and kiang), followed by the African zebras (subgenera E. (Dolichohippus), and E. (Hippotigris)).

Subsequently, populations of this species entered South America as part of the Great American Interchange shortly after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama, and evolved into the form currently referred to as Hippidion ~2.5 million years ago.

Both the NWSLH and Hippidium show adaptations to dry, barren ground, whereas the shortened legs of Hippidion may have been a response to sloped terrain.

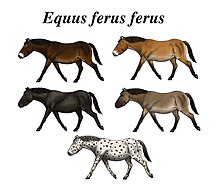

However, genetic results on extant and fossil material of Pleistocene age indicate two clades, potentially subspecies, one of which had a holarctic distribution spanning from Europe through Asia and across North America and would become the founding stock of the modern domesticated horse.

[38] An analysis based on whole genome sequencing and calibration with DNA from old horse bones gave a divergence date of 38–72 thousand years ago.

[39] In June 2013, a group of researchers announced that they had sequenced the DNA of a 560–780 thousand year old horse, using material extracted from a leg bone found buried in permafrost in Canada's Yukon territory.

[41] Analysis of differences between these genomes indicated that the last common ancestor of modern horses, donkeys, and zebras existed 4 to 4.5 million years ago.

For example, in Alaska, beginning approximately 12,500 years ago, the grasses characteristic of a steppe ecosystem gave way to shrub tundra, which was covered with unpalatable plants.

[46][47] The other hypothesis suggests extinction was linked to overexploitation by newly arrived humans of naive prey that were not habituated to their hunting methods.

[53] In Eurasia, horse fossils began occurring frequently again in archaeological sites in Kazakhstan and the southern Ukraine about 6,000 years ago.

Subsequent explorers, such as Coronado and De Soto, brought ever-larger numbers, some from Spain and others from breeding establishments set up by the Spanish in the Caribbean.

[citation needed] The ancestral coat color of E. ferus was possibly a uniform dun, consistent with modern populations of Przewalski's horses.