Quantum gravity

It deals with environments in which neither gravitational nor quantum effects can be ignored,[1] such as in the vicinity of black holes or similar compact astrophysical objects, as well as in the early stages of the universe moments after the Big Bang.

At distances close to the Planck length, like those near the center of a black hole, quantum fluctuations of spacetime are expected to play an important role.

[7] All of these approaches aim to describe the quantum behavior of the gravitational field, which does not necessarily include unifying all fundamental interactions into a single mathematical framework.

In the early 21st century, new experiment designs and technologies have arisen which suggest that indirect approaches to testing quantum gravity may be feasible over the next few decades.

No theory has yet proven successful in describing the general situation where the dynamics of matter, modeled with quantum mechanics, affect the curvature of spacetime.

[18] It is widely hoped that a theory of quantum gravity would allow us to understand problems of very high energy and very small dimensions of space, such as the behavior of black holes, and the origin of the universe.

Under mild assumptions, the structure of general relativity requires them to follow the quantum mechanical description of interacting theoretical spin-2 massless particles.

[24][25] While gravitons are an important theoretical step in a quantum mechanical description of gravity, they are generally believed to be undetectable because they interact too weakly.

At low energies, the logic of the renormalization group tells us that, despite the unknown choices of these infinitely many parameters, quantum gravity will reduce to the usual Einstein theory of general relativity.

On the other hand, if we could probe very high energies where quantum effects take over, then every one of the infinitely many unknown parameters would begin to matter, and we could make no predictions at all.

[29] It is conceivable that, in the correct theory of quantum gravity, the infinitely many unknown parameters will reduce to a finite number that can then be measured.

Since this is a question of non-perturbative quantum field theory, finding a reliable answer is difficult, pursued in the asymptotic safety program.

[32] By treating general relativity as an effective field theory, one can actually make legitimate predictions for quantum gravity, at least for low-energy phenomena.

While simple to grasp in principle, this is a complex idea to understand about general relativity, and its consequences are profound and not fully explored, even at the classical level.

[38] Currently, there is still no complete and consistent quantum theory of gravity, and the candidate models still need to overcome major formal and conceptual problems.

They also face the common problem that, as yet, there is no way to put quantum gravity predictions to experimental tests, although there is hope for this to change as future data from cosmological observations and particle physics experiments become available.

This is derived from the following considerations: In the case of electromagnetism, the quantum operator representing the energy of each frequency of the field has a discrete spectrum.

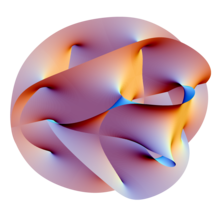

Spin networks were initially introduced by Roger Penrose in abstract form, and later shown by Carlo Rovelli and Lee Smolin to derive naturally from a non-perturbative quantization of general relativity.

The theory is based on the reformulation of general relativity known as Ashtekar variables, which represent geometric gravity using mathematical analogues of electric and magnetic fields.

Since theoretical development has been slow, the field of phenomenological quantum gravity, which studies the possibility of experimental tests, has obtained increased attention.

[67] The latter scenario has been searched for in light from gamma-ray bursts and both astrophysical and atmospheric neutrinos, placing limits on phenomenological quantum gravity parameters.

[68][69][70] ESA's INTEGRAL satellite measured polarization of photons of different wavelengths and was able to place a limit in the granularity of space that is less than 10−48 m, or 13 orders of magnitude below the Planck scale.

[71][72][better source needed] The BICEP2 experiment detected what was initially thought to be primordial B-mode polarization caused by gravitational waves in the early universe.

Had the signal in fact been primordial in origin, it could have been an indication of quantum gravitational effects, but it soon transpired that the polarization was due to interstellar dust interference.