Quantum dot cellular automaton

Any device designed to represent data and perform computation, regardless of the physics principles it exploits and materials used to build it, must have two fundamental properties: distinguishability and conditional change of state, the latter implying the former.

For example, in a digital electronic system, transistors play the role of such controllable energy barriers, making it extremely practical to perform computing with them.

A cellular automaton (CA) is a discrete dynamical system consisting of a uniform (finite or infinite) grid of cells.

Lent combined the discrete nature of both cellular automata and quantum mechanics, to create nano-scale devices capable of performing computation at very high switching speeds (order of Terahertz) and consuming extremely small amounts of electrical power.

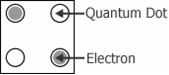

Just like any CA, Quantum (-dot) Cellular Automata are based on the simple interaction rules between cells placed on a grid.

The bounding boxes in the figure do not represent physical implementation, but are shown as means to identify individual cells.

In contrast with an orthogonal placement, the electric field effect of this input structure forces a reversal of polarization in the output.

However, a method to control data flow is necessary to define the direction in which state transition occurs in QCA cells.

The clocks of a QCA system serve two purposes: powering the automaton, and controlling data flow direction.

A new kind of cell pattern potentially introduces as much as twice the amount of fabrication cost and infrastructure; the number of possible quantum dot locations on an interstitial grid is doubled and an overall increase in geometric design complexity is inevitable.

This degrades the performance of the device in terms of maximum operating temperature, resistance to entropy, and switching speed.

A different wire-crossing technique, which makes fabrication of QCA devices more practical, was presented by Christopher Graunke, David Wheeler, Douglas Tougaw, and Jeffrey D. Will, in their paper “Implementation of a crossbar network using quantum-dot cellular automata”.

Their wire-crossing technique introduces the concept of implementing QCA devices capable of performing computation as a function of synchronization.

Thus, the fabrication problem stated earlier is fully addressed by: a) using only one type of quantum-dot pattern and, b) by the ability to make a universal QCA building block of adequate complexity, which function is determined only by its timing mechanism (i.e., its clocks).

As a consequence, a device exploiting this method of function implementation may perform significantly slower than its traditional counterpart.

It was not originally intended to compete with current technology in the sense of speed and practicality, as its structural properties are not suitable for scalable designs.

Because of the relatively large-sized islands, metal-island devices had to be kept at extremely low temperatures for quantum effects (electron switching) to be observable.

However, current semiconductor processes have not yet reached a point where mass production of devices with such small features (≈20 nanometers) is possible.

[citation needed] Serial lithographic methods, however, make QCA solid state implementation achievable, but not necessarily practical.

[citation needed] A proposed but not yet implemented method consists of building QCA devices out of single molecules.

A number of technical challenges, including choice of molecules, the design of proper interfacing mechanisms, and clocking technology remain to be solved before this method can be implemented.

In MQCA, the term “Quantum” refers to the quantum-mechanical nature of magnetic exchange interactions and not to the electron-tunneling effects.