Measurement in quantum mechanics

Applying the Born rule to these amplitudes gives the probabilities that the electron will be found in one region or another when an experiment is performed to locate it.

The same quantum state can also be used to make a prediction of how the electron will be moving, if an experiment is performed to measure its momentum instead of its position.

The approach codified by John von Neumann represents a measurement upon a physical system by a self-adjoint operator on that Hilbert space termed an "observable".

Indeed, introductory physics texts on quantum mechanics often gloss over mathematical technicalities that arise for continuous-valued observables and infinite-dimensional Hilbert spaces, such as the distinction between bounded and unbounded operators; questions of convergence (whether the limit of a sequence of Hilbert-space elements also belongs to the Hilbert space), exotic possibilities for sets of eigenvalues, like Cantor sets; and so forth.

[16][17] If the POVM is itself a PVM, then the Kraus operators can be taken to be the projectors onto the eigenspaces of the von Neumann observable: If the initial state

[9]: 91 We can define a linear, trace-preserving, completely positive map, by summing over all the possible post-measurement states of a POVM without the normalisation: It is an example of a quantum channel,[10]: 150 and can be interpreted as expressing how a quantum state changes if a measurement is performed but the result of that measurement is lost.

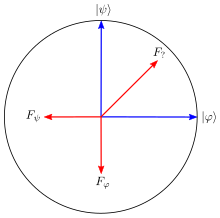

, so by normalization, An arbitrary state for a qubit can be written as a linear combination of the Pauli matrices, which provide a basis for

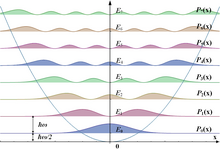

The set of possible outcomes of a position measurement on a harmonic oscillator is continuous, and so predictions are stated in terms of a probability density function

The Stern–Gerlach experiment, proposed in 1921 and implemented in 1922,[27][28][29] became a prototypical example of a quantum measurement having a discrete set of possible outcomes.

In the original experiment, silver atoms were sent through a spatially varying magnetic field, which deflected them before they struck a detector screen, such as a glass slide.

The screen reveals discrete points of accumulation, rather than a continuous distribution, owing to the particles' quantized spin.

At the time, and in contrast with the later standard presentation of quantum mechanics, Heisenberg did not regard the position of an electron bound within an atom as "observable".

It is frequently attributed to Heisenberg, who introduced the concept in analyzing a thought experiment where one attempts to measure an electron's position and momentum simultaneously.

The existence of the uncertainty principle naturally raises the question of whether quantum mechanics can be understood as an approximation to a more exact theory.

A collection of results, most significantly Bell's theorem, have demonstrated that broad classes of such hidden-variable theories are in fact incompatible with quantum physics.

Bell published the theorem now known by his name in 1964, investigating more deeply a thought experiment originally proposed in 1935 by Einstein, Podolsky and Rosen.

If a Bell test is performed in a laboratory and the results are not thus constrained, then they are inconsistent with the hypothesis that local hidden variables exist.

Such results would support the position that there is no way to explain the phenomena of quantum mechanics in terms of a more fundamental description of nature that is more in line with the rules of classical physics.

To date, Bell tests have found that the hypothesis of local hidden variables is inconsistent with the way that physical systems behave.

Beginning in the 1950s, Rosenfeld, von Weizsäcker and others tried to develop consistency conditions that expressed when a quantum-mechanical system could be treated as a measuring apparatus.

This phenomenon of entanglement produced by system-environment interactions tends to obscure the more exotic features of quantum mechanics that the system could in principle manifest.

[45] (Earlier investigations into how classical physics might be obtained as a limit of quantum mechanics had explored the subject of imperfectly isolated systems, but the role of entanglement was not fully appreciated.

[55] In the early years of the subject, laboratory procedures involved the recording of spectral lines, the darkening of photographic film, the observation of scintillations, finding tracks in cloud chambers, and hearing clicks from Geiger counters.

The first interference experiment to be carried out in a regime where both wave-like and particle-like aspects of photon behavior are significant was G. I. Taylor's test in 1909.

Taylor used screens of smoked glass to attenuate the light passing through his apparatus, to the extent that, in modern language, only one photon would be illuminating the interferometer slits at a time.

He recorded the interference patterns on photographic plates; for the dimmest light, the exposure time required was roughly three months.

[58][59] In 1974, the Italian physicists Pier Giorgio Merli, Gian Franco Missiroli, and Giulio Pozzi implemented the double-slit experiment using single electrons and a television tube.

[62] Despite the consensus among scientists that quantum physics is in practice a successful theory, disagreements persist on a more philosophical level.

Von Neumann declared that quantum mechanics contains "two fundamentally different types" of quantum-state change.

However, consensus has not been achieved among proponents of the correct way to implement this program, and in particular how to justify the use of the Born rule to calculate probabilities.