Quantum nonlocality

[1][2][3][4][5] Quantum nonlocality does not allow for faster-than-light communication,[6] and hence is compatible with special relativity and its universal speed limit of objects.

[7] In the 1935 EPR paper,[8] Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen described "two spatially separated particles which have both perfectly correlated positions and momenta"[9] as a direct consequence of quantum theory.

[14] This steering occurs in such a way that no signal can be sent by performing such a state update; quantum nonlocality cannot be used to send messages instantaneously and is therefore not in direct conflict with causality concerns in special relativity.

Although various authors (most notably Niels Bohr) criticised the ambiguous terminology of the EPR paper,[15][16] the thought experiment nevertheless generated a great deal of interest.

Their notion of a "complete description" was later formalised by the suggestion of hidden variables that determine the statistics of measurement results, but to which an observer does not have access.

[19] In 1964 John Bell answered Einstein's question by showing that such local hidden variables can never reproduce the full range of statistical outcomes predicted by quantum theory.

[20] Bell showed that a local hidden variable hypothesis leads to restrictions on the strength of correlations of measurement results.

However, Bell notes that the non-local hidden variable model of Bohm are different:[20] This [grossly nonlocal structure] is characteristic ... of any such theory which reproduces exactly the quantum mechanical predictions.Clauser, Horne, Shimony and Holt (CHSH) reformulated these inequalities in a manner that was more conducive to experimental testing (see CHSH inequality).

Bell's demonstration is probabilistic in the sense that it shows that the precise probabilities predicted by quantum mechanics for some entangled scenarios cannot be met by a local hidden variable theory.

The work of Bancal et al.[27] generalizes Bell's result by proving that correlations achievable in quantum theory are also incompatible with a large class of superluminal hidden variable models.

In this scenario, any bipartite experiment revealing Bell nonlocality can just provide lower bounds on the hidden influence's propagation speed.

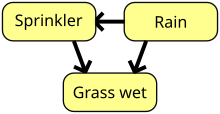

Bell's theorem can thus be interpreted as a separation between the quantum and classical predictions in a type of causal structures with just one hidden node

[28] The characterization of the boundaries for classical correlations in such extended Bell scenarios is challenging, but there exist complete practical computational methods to achieve it.

Consider the CHSH Bell scenario detailed before, but this time assume that, in their experiments, Alice and Bob are preparing and measuring quantum systems.

In the above definition, the space-like separation of the two parties conducting the Bell experiment was modeled by imposing that their associated operator algebras act on different factors

[42] In January 2020, Ji, Natarajan, Vidick, Wright, and Yuen claimed a result in quantum complexity theory[43] that would imply that

At the level of correlations between two parties, Einstein's causality translates in the requirement that Alice's measurement choice should not affect Bob's statistics, and vice versa.

[59] In view of this mismatch, Popescu and Rohrlich pose the problem of identifying a physical principle, stronger than the no-signalling conditions, that allows deriving the set of quantum correlations.

However, it is not a void principle: on the contrary, in [65] it is shown that many simple, intuitive families of sets of correlations in probability space happen to violate it.

[66] Nonlocality can be exploited to conduct quantum information tasks which do not rely on the knowledge of the inner workings of the prepare-and-measurement apparatuses involved in the experiment.

[67] In this primitive, two distant parties, Alice and Bob, are distributed an entangled quantum state, that they probe, thus obtaining the statistics

This estimation allows them to devise a reconciliation protocol at the end of which Alice and Bob share a perfectly correlated one-time pad of which Eve has no information whatsoever.

These techniques have critical applications in cryptography, where high-quality random numbers are essential for ensuring the security of cryptographic protocols.

Recent research has demonstrated the feasibility of DI randomness certification using entangled quantum systems, such as photons or electrons.

Recent research has shown that DI randomness expansion can be achieved using entangled photon pairs and measurement devices that violate a Bell inequality.

The security of the amplification is guaranteed by the fact that any attempt by an adversary to manipulate the algorithm's output will inevitably introduce errors that can be detected and corrected.

Recent research has demonstrated the feasibility of DI randomness amplification using quantum entanglement and the violation of a Bell inequality.

This phenomenon, that can be interpreted as an instance of device-independent quantum tomography, was first pointed out by Tsirelson[40] and named self-testing by Mayers and Yao.

[77] Finding lower bounds on the Hilbert space dimension based on statistics happens to be a hard task, and current general methods only provide very low estimates.

[78] However, a Bell scenario with five inputs and three outputs suffices to provide arbitrarily high lower bounds on the underlying Hilbert space dimension.