Quartz clock

Generally, some form of digital logic counts the cycles of this signal and provides a numerical time display, usually in units of hours, minutes, and seconds.

[2] This frequency is a power of two (32768 = 215), just high enough to exceed the human hearing range, yet low enough to keep electric energy consumption, cost and size at a modest level and to permit inexpensive counters to derive a 1-second pulse.

Some analog quartz clocks feature a sweep second hand moved by a non-stepped battery or mains powered electric motor, often resulting in reduced mechanical output noise.

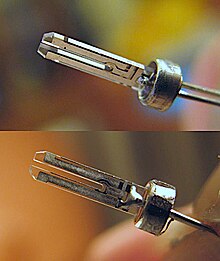

In modern standard-quality quartz clocks, the quartz-crystal resonator or oscillator is cut in the shape of a small tuning fork (XY-cut), laser-trimmed or precision-lapped to vibrate at 32768 Hz.

A power of 2 is chosen so a simple chain of digital divide-by-2 stages can derive the 1 Hz signal needed to drive the watch's second hand.

Standard-quality 32768 Hz resonators of this type are warranted to have a long-term accuracy of about six parts per million (0.0006%) at 31 °C (87.8 °F): that is, a typical quartz clock or wristwatch will gain or lose 15 seconds per 30 days (within a normal temperature range of 5 to 35 °C or 41 to 95 °F) or less than a half second clock drift per day when worn near the body.

Though quartz has a very low coefficient of thermal expansion, temperature changes are the major cause of frequency variation in crystal oscillators.

[10] A well-chosen turnover point can minimize the negative effect of temperature-induced frequency drift, and hence improve the practical timekeeping accuracy of a consumer-grade crystal oscillator without adding significant cost.

Autonomous high-accuracy quartz movements, even in wristwatches, can be accurate to within ±1 to ±25 seconds per year and can be certified and used as marine chronometers to determine longitude (the East–West position of a point on the Earth's surface) by means of celestial navigation.

[13] The frequency dividers remain unchanged, so the trimmer condenser can be used to adjust the electric pulse-per-second (or other desired time interval) output.

Few newer quartz movement designs feature a mechanical trimmer condenser and rely on generally digital correction methods.

For this the movement autonomously measures the crystal's temperature a few hundred to a few thousand times a day and compensates for this with a small calculated offset.

In more expensive high-end quartz watches, thermal compensation can be implemented by varying the number of cycles to inhibit depending on the output from a temperature sensor.

[21] AT-cut variations allow for greater temperature tolerances, specifically in the range of −40 to 125 °C (−40 to 257 °F), they exhibit reduced deviations caused by gravitational orientation changes.

After manufacturing, each module is calibrated against a precision clock at the factory and adjusted to keep accurate time by programming the digital logic to skip a small number of crystal cycles at regular intervals, such as 10 seconds or 1 minute.

The advantage of this method is that using digital programming to store the number of pulses to suppress in a non-volatile memory register on the chip is less expensive than the older technique of trimming the quartz tuning-fork frequency.

[25] Clock quartz crystals are manufactured in an ultra-clean environment, then protected by an inert ultra-high vacuum in hermetically sealed containers.

[26] Factors that can cause a small frequency drift over time are stress relief in the mounting structure, loss of hermetic seal, contamination of the crystal lattice, moisture absorption, changes in or on the quartz crystal, severe shock and vibrations effects, and exposure to very high temperatures.

[27] Crystal aging tends to be logarithmic, meaning the maximum rate of change of frequency occurs immediately after manufacture and decays thereafter.

As a result, the mechanical output of analog quartz clock movements may temporarily stop, advance or reverse and negatively impact correct timekeeping.

Some quartz wristwatch testers feature a magnetic field function to test if the stepping motor can provide mechanical output and let the gear train and hands deliberately spin overly fast to clear minor fouling.

[32] An electrical oscillator was first used to sustain the motion of a tuning fork by the British physicist William Eccles in 1919;[33] his achievement removed much of the damping associated with mechanical devices and maximised the stability of the vibration's frequency.

In October 1927 the first quartz clock was described and built by Joseph W. Horton and Warren A. Marrison at Bell Telephone Laboratories.

[38] The next 3 decades saw the development of quartz clocks as precision time standards in laboratory settings; the bulky delicate counting electronics, built with vacuum tubes, limited their use elsewhere.

In 1932 a quartz clock was able to measure tiny variations in the rotation rate of the Earth over periods as short as a few weeks.

[39] In Japan in 1932, Issac Koga developed a crystal cut that gave an oscillation frequency with greatly reduced temperature dependence.

[citation needed] Their inherent physical and chemical stability and accuracy have resulted in the subsequent proliferation, and since the 1940s they have formed the basis for precision measurements of time and frequency worldwide.

[46] In 1966, prototypes of the world's first quartz pocket watch were unveiled by Seiko and Longines in the Neuchâtel Observatory's 1966 competition.

The inherent accuracy and eventually achieved low cost of production have resulted in the proliferation of quartz clocks and watches since that time.

Standard 'Watch' or Real-time clock (RTC) crystal units have become cheap mass-produced items on the electronic parts market.