Quechua people

There have been later tendencies toward nation-building among Quechua speakers, particularly in Ecuador (Kichwa) but also in Bolivia, where there are only slight linguistic differences from the original Peruvian version.

The typical Andean community extends over several altitude ranges and thus includes the cultivation of a variety of arable crops and/or livestock.

Beginning with the colonial era and intensifying after the South American states had gained their independence, large landowners appropriated all or most of the land and forced the Native population into bondage (known in Ecuador as Huasipungo, from Kichwa wasipunku, "front door").

The largest of these revolts occurred in 1780–1781 under the leadership of Husiy Qawriyil Kunturkanki.Some Indigenous farmers re-occupied their ancestors' lands and expelled the landlords during the takeover of governments by dictatorships in the middle of the 20th century, such as in 1952 in Bolivia (Víctor Paz Estenssoro) and 1968 in Peru (Juan Velasco Alvarado).

The Kichwa ethnic groups of Ecuador which are part of the ECUARUNARI association were recently able to regain communal land titles or the return of estates—in some cases through militant activity.

Especially the case of the community of Sarayaku has become well known among the Kichwa of the lowlands, who after years of struggle were able to successfully resist expropriation and exploitation of the rain forest for petroleum recovery.

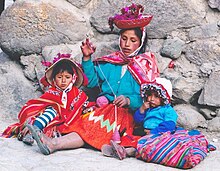

This includes a tradition of weaving handed down from Inca times or earlier, using cotton, wool (from llamas, alpacas, guanacos, and vicuñas), and a multitude of natural dyes, and incorporating numerous woven patterns (pallay).

The disintegration of the traditional economy, for example, regionally through mining activities and accompanying proletarian social structures, has usually led to a loss of both ethnic identity and the Quechua language.

[17][18] Pachamanca, a Quechua word for a pit cooking technique used in Peru, includes several types of meat such as chicken, beef, pork, lamb, and/or mutton; tubers such as potatoes, sweet potatoes, yucca, uqa/ok’a (oca in Spanish), and mashwa; other vegetables such as maize/corn and fava beans; seasonings; and sometimes cheese in a small pot and/or tamales.

In the internal conflict in Peru in the 1980s between the government and Sendero Luminoso about three-quarters of the estimated 70,000 death toll were Quechuas, whereas the war parties were without exception whites and mestizos (people with mixed descent from both Natives and Spaniards).

[21] The forced sterilization policy under Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori affected almost exclusively Quechua and Aymara women, a total of about 270,000 (and 22,000 men) according to official figures.

The Quechuas have been subject to these severe inequalities, as many of them have a much lower life expectancy than the regional average, and many communities lack access to basic health services.

When the newly elected Peruvian members of parliament Hilaria Supa Huamán and María Sumire swore their oath of office in Quechua—for the first time in the history of Peru in an Indigenous language—the Peruvian parliamentary president Martha Hildebrandt and the parliamentary officer Carlos Torres Caro refused their acceptance.

Quechua ethnic groups also share traditional religions with other Andean peoples, particularly belief in Mother Earth (Pachamama), who grants fertility and to whom burnt offerings and libations are regularly made.

These include the figure of Nak'aq or Pishtaco ("butcher"), the white murderer who sucks out the fat from the bodies of the Indigenous peoples he kills,[27] and a song about a bloody river.

[29][30][31] Some Quechuas consider classic products of the region such as corn beer, chicha, coca leaves, and local potatoes as having a religious significance, but this belief is not uniform across communities.

When chewed, coca acts as a mild stimulant and suppresses hunger, thirst, pain, and fatigue; it is also used to alleviate altitude sickness.

Starting at puberty, Quechua girls begin wearing multiple layers of petticoats and skirts, showing off the family's wealth and making her a more desirable bride.

Younger Quechua men generally wear Western-style clothing, the most popular being synthetic football shirts and tracksuit trousers.

Men's fine dress includes a woolen waistcoat, similar to a sleeveless juyuna as worn by women but referred to as a chaleco, and often richly decorated.