Alexandra of Denmark

Alexandra's family had been relatively obscure until 1852, when her father, Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, was chosen with the consent of the major European powers to succeed his second cousin Frederick VII as King of Denmark.

At the age of sixteen, Alexandra was chosen as the future wife of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the son and heir apparent of Queen Victoria.

Largely excluded from wielding any political power, she unsuccessfully attempted to sway the opinion of British ministers and her husband's family to favour Greek and Danish interests.

Her father's family was a distant cadet branch of the Danish royal House of Oldenburg, which was descended from King Christian III.

They did not possess great wealth; her father's income from an army commission was about £800 per year, and their house was a rent-free grace and favour property.

Although the family's status had risen, there was little or no increase in their income; and they did not participate in court life at Copenhagen, for they refused to meet Frederick's third wife and former mistress, Louise Rasmussen, because she had an illegitimate child by a previous lover.

[13] A few months later, Alexandra travelled from Denmark to Britain aboard the royal yacht Victoria and Albert and arrived in Gravesend, Kent, on 7 March 1863.

[15] As the couple left Windsor for their honeymoon at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, they were cheered by the schoolboys of neighbouring Eton College, including Lord Randolph Churchill.

To the great irritation of Queen Victoria and the Crown Princess of Prussia, Alexandra and Albert Edward supported the Danish side in the war.

The Prussian conquest of former Danish lands heightened Alexandra's profound dislike of the Germans, a feeling which stayed with her for the rest of her life.

[19] During the birth of her third child in 1867, the added complication of a bout of rheumatic fever threatened Alexandra's life and left her with a permanent limp.

Biographers agree that their marriage was in many ways a happy one; however, some have asserted that Albert Edward did not give his wife as much attention as she would have liked and that they gradually became estranged, until his attack of typhoid fever (the disease which was believed to have killed his father) in late 1871 brought about a reconciliation.

[29] Throughout their marriage Albert Edward continued to keep company with other women, including the actress Lillie Langtry, Daisy Greville, Countess of Warwick, humanitarian Agnes Keyser, and society matron Alice Keppel.

[31] An increasing degree of deafness, caused by hereditary otosclerosis, led to Alexandra's social isolation; she spent more time at home with her children and pets.

Despite Alexandra's pleas for privacy, Queen Victoria insisted on announcing a period of court mourning, which led unsympathetic elements of the press to describe the birth as "a wretched abortion" and the funeral arrangements as "sickening mummery", even though the infant was not buried in state with other members of the royal family at Windsor, but in strict privacy in the churchyard at Sandringham, where he had lived out his brief life.

Distressed at their threats, and following the advice of Sir William Knollys and the Duchess of Teck, Alexandra informed the Queen, who then wrote to the Prince of Wales.

She opens bazaars, attends concerts, visits hospitals in my place ... she not only never complains, but endeavours to prove that she has enjoyed what to another would be a tiresome duty.

Just two months later, her son George and daughter-in-law Mary left on an extensive tour of the empire, leaving their young children in the care of Alexandra and Edward, who doted on their grandchildren.

[48] Eventually, the coronation had to be postponed and Edward had an operation performed by Frederick Treves of the London Hospital to drain the infected appendix.

Eager to retain their family links, both to each other and to Denmark, in 1907 Alexandra and her sister, the Dowager Empress of Russia, purchased a villa north of Copenhagen, Hvidøre, as a private getaway.

[53] Alexandra was denied access to the King's briefing papers and excluded from some of his foreign tours to prevent her meddling in diplomatic matters.

The Germans fortified the island and, in the words of Robert Ensor and as Alexandra had predicted, it "became the keystone of Germany's maritime position for offence as well as for defence".

In a remarkable departure from precedent, for two hours she sat in the Ladies' Gallery overlooking the chamber while the Parliament Bill, to remove the right of the House of Lords to veto legislation, was debated.

Despite her personal views, Alexandra supported her son's reluctant agreement to Prime Minister H. H. Asquith's request to create sufficient Liberal peers after a general election if the Lords continued to block the legislation.

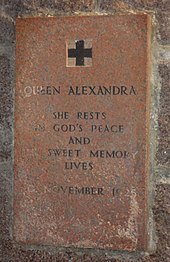

Queen Alexandra lay in state at Westminster Abbey and was interred on 28 November next to her husband in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.

[80] The management of her finances was left in the hands of her loyal comptroller, Sir Dighton Probyn VC, who undertook a similar role for her husband.

"[81] Though she was not always extravagant (she had her old stockings darned for re-use and her old dresses were recycled as furniture covers),[82] she would dismiss protests about her heavy spending with a wave of a hand or by claiming that she had not heard.

[83] Alexandra hid a small scar on her neck, which was probably the result of a childhood operation,[84] by wearing choker necklaces and high necklines, setting fashions which were adopted for fifty years.

[85] Alexandra's effect on fashion was so profound that society ladies even copied her limping gait, after her serious illness in 1867 left her with a stiff leg.

[82] Alexandra has been portrayed on television by Deborah Grant and Helen Ryan in Edward the Seventh, Ann Firbank in Lillie, Maggie Smith in All the King's Men, and Bibi Andersson in The Lost Prince.