Quine–Putnam indispensability argument

A standard form of the argument in contemporary philosophy is credited to Mark Colyvan; whilst being influenced by both Quine and Putnam, it differs in important ways from their formulations.

It is presented in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:[2] Nominalists, philosophers who reject the existence of abstract objects, have argued against both premises of this argument.

Other philosophers, including Penelope Maddy, Elliott Sober, and Joseph Melia, have argued that we do not need to believe in all of the entities that are indispensable to science.

[12] The indispensability argument aims to overcome the epistemological problem posed against platonism by providing a justification for belief in abstract mathematical objects.

It does not necessarily justify belief in the most abstract parts of set theory, which Quine called "mathematical recreation … without ontological rights".

Instead of referring to numerical distances, Field's reformulation uses relationships such as "between" and "congruent" to recover the theory without implying the existence of numbers.

[31] John Burgess and Mark Balaguer have taken steps to extend this nominalizing project to areas of modern physics, including quantum mechanics.

If they challenge your credentials, will you boast of philosophy's other great discoveries: that motion is impossible, that a Being than which no greater can be conceived cannot be conceived not to exist, that it is unthinkable that anything exists outside the mind, that time is unreal, that no theory has ever been made at all probable by evidence (but on the other hand that an empirically adequate ideal theory cannot possibly be false), that it is a wide-open scientific question whether anyone has ever believed anything, and so on, and on, ad nauseam?

Similarly, Charles Parsons has argued that mathematical truths seem immediately obvious in a way that suggests they do not depend on the results of our best theories.

[50] An example of this idea provided by Michael Resnik is of the hypothesis that an observer will see oil and water separate out if they are added together because they do not mix.

[54] Maddy, and others such as Mary Leng, also appeal to the fact that scientists use mathematical idealizations—such as assuming bodies of water to be infinitely deep—without regard for whether they are true.

[56] Since these counterarguments have been raised, a number of philosophers—including Resnik, Alan Baker, Patrick Dieveney, David Liggins, Jacob Busch, and Andrea Sereni—have argued that confirmational holism can be eliminated from the argument.

[57] For example, Resnik has offered a pragmatic indispensability argument focused less on the notion of evidence and more on the practical importance of mathematics in conducting scientific enquiry.

But according to Azzouni, mathematical entities are "mere posits" that can be postulated by anyone at any time by "simply writing down a set of axioms", so we do not need to treat them as real.

[69] But according to Melia, mathematics plays a purely representational role in science, it merely "[makes] more things sayable about concrete objects".

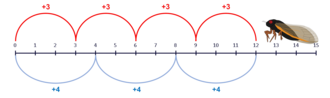

Baker said that this is an explanation in which mathematics, specifically number theory, plays a key role in explaining an empirical phenomenon.

[80] Other important examples are explanations of the hexagonal structure of bee honeycombs and the impossibility of crossing all seven bridges of Königsberg only once in a walk across the city.

[82] The argument is historically associated with Willard Van Orman Quine and Hilary Putnam but it can be traced to earlier thinkers such as Gottlob Frege and Kurt Gödel.

Duhem responded by saying that the law produces predictions when paired with auxiliary hypotheses fixing the frame of reference and is therefore no different from any other physical theory.

It sees natural science as an inquiry into reality, fallible and corrigible but not answerable to any supra-scientific tribunal, and not in need of any justification beyond observation and the hypothetico-deductive method.

[92] For the logical positivists, all justified beliefs were reducible to sense data, including our knowledge of ordinary objects such as trees.

[93] Whilst he eventually became a platonist due to his formulation of the indispensability argument,[95] Quine was sympathetic to nominalism from the early stages of his career.

[97] He and Nelson Goodman subsequently released a joint 1947 paper titled "Steps toward a Constructive Nominalism"[98] as part of an ongoing project of Quine's to "set up a nominalistic language in which all of natural science can be expressed".

[103] According to Lieven Decock, Quine had accepted the need for abstract mathematical entities by the publication of his 1960 book Word and Object, in which he wrote "a thoroughgoing nominalist doctrine is too much to live up to".

[107] He also wrote Quine had "for years stressed both the indispensability of quantification over mathematical entities and the intellectual dishonesty of denying the existence of what one daily presupposes".

The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy states: "In his early work, Hilary Putnam accepted Quine's version of the indispensability argument.

[116] Chihara, in his 1973 book Ontology and the Vicious Circle Principle, was one of the earliest philosophers to attempt to reformulate mathematics in response to Quine's arguments.

Quine's version of the argument relies on translating scientific theories from ordinary language into first-order logic to determine its ontological commitments, which is not explicitly required by Colyvan's formulation.

For example, David Lewis, who was a student of Quine, used an indispensability argument to argue for modal realism in his 1986 book On the Plurality of Worlds.

[130] In the field of ethics, David Enoch has expanded the criterion of ontological commitment used in the Quine–Putnam indispensability argument to argue for moral realism.