Horace

The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his Odes as the only Latin lyrics worth reading: "He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words.

For some commentators, his association with the regime was a delicate balance in which he maintained a strong measure of independence (he was "a master of the graceful sidestep")[2] but for others he was, in John Dryden's phrase, "a well-mannered court slave".

[16] The term 'coactor' could denote various roles, such as tax collector, but its use by Horace[17] was explained by scholia as a reference to 'coactor argentarius' i.e. an auctioneer with some of the functions of a banker, paying the seller out of his own funds and later recovering the sum with interest from the buyer.

[16] Horace left Rome, possibly after his father's death, and continued his formal education in Athens, a great centre of learning in the ancient world, where he arrived at nineteen years of age, enrolling in The Academy.

Brutus was fêted around town in grand receptions and he made a point of attending academic lectures, all the while recruiting supporters among the young men studying there, including Horace.

The comparison with the latter poet is uncanny: Archilochus lost his shield in a part of Thrace near Philippi, and he was deeply involved in the Greek colonization of Thasos, where Horace's die-hard comrades finally surrendered.

He describes[31] in glowing terms the country villa which his patron, Maecenas, had given him in a letter to his friend Quinctius: "It lies on a range of hills, broken by a shady valley which is so placed that the sun when rising strikes the right side, and when descending in his flying chariot, warms the left.

You would like the climate; and if you were to see my fruit trees, bearing ruddy cornils and plums, my oaks and ilex supplying food to my herds, and abundant shade to the master, you would say, Tarentum in its beauty has been brought near to Rome!

Philosophy was drifting into absorption in self, a quest for private contentedness, to be achieved by self-control and restraint, without much regard for the fate of a disintegrating community.Horace's Hellenistic background is clear in his Satires, even though the genre was unique to Latin literature.

He depicted the process as an honourable one, based on merit and mutual respect, eventually leading to true friendship, and there is reason to believe that his relationship was genuinely friendly, not just with Maecenas but afterwards with Augustus as well.

However, most Romans considered the civil wars to be the result of contentio dignitatis, or rivalry between the foremost families of the city, and he too seems to have accepted the principate as Rome's last hope for much needed peace.

The fragmented nature of the Greek world had enabled his literary heroes to express themselves freely and his semi-retirement from the Treasury in Rome to his own estate in the Sabine hills perhaps empowered him to some extent also[49] yet even when his lyrics touched on public affairs they reinforced the importance of private life.

[54] In the final poem of the first book of Epistles, he revealed himself to be forty-four years old in the consulship of Lollius and Lepidus i.e. 21 BC, and "of small stature, fond of the sun, prematurely grey, quick-tempered but easily placated".

[59] He was also commissioned to write odes commemorating the victories of Drusus and Tiberius[60] and one to be sung in a temple of Apollo for the Secular Games, a long-abandoned festival that Augustus revived in accordance with his policy of recreating ancient customs (Carmen Saeculare).

Suetonius recorded some gossip about Horace's sexual activities late in life, claiming that the walls of his bedchamber were covered with obscene pictures and mirrors, so that he saw erotica wherever he looked.

There are persuasive arguments for the following chronology:[62] Horace composed in traditional metres borrowed from Archaic Greece, employing hexameters in his Satires and Epistles, and iambs in his Epodes, all of which were relatively easy to adapt into Latin forms.

[63] As soon as Horace, stirred by his own genius and encouraged by the example of Virgil, Varius, and perhaps some other poets of the same generation, had determined to make his fame as a poet, being by temperament a fighter, he wanted to fight against all kinds of prejudice, amateurish slovenliness, philistinism, reactionary tendencies, in short to fight for the new and noble type of poetry which he and his friends were endeavouring to bring about.In modern literary theory, a distinction is often made between immediate personal experience (Urerlebnis) and experience mediated by cultural vectors such as literature, philosophy and the visual arts (Bildungserlebnis).

[68] Horace generally followed the examples of poets established as classics in different genres, such as Archilochus in the Epodes, Lucilius in the Satires and Alcaeus in the Odes, later broadening his scope for the sake of variation and because his models weren't actually suited to the realities confronting him.

Archilochus and Alcaeus were aristocratic Greeks whose poetry had a social and religious function that was immediately intelligible to their audiences but which became a mere artifice or literary motif when transposed to Rome.

However, the artifice of the Odes is also integral to their success, since they could now accommodate a wide range of emotional effects, and the blend of Greek and Roman elements adds a sense of detachment and universality.

Whereas Archilochus presented himself as a serious and vigorous opponent of wrong-doers, Horace aimed for comic effects and adopted the persona of a weak and ineffectual critic of his times (as symbolized for example in his surrender to the witch Canidia in the final epode).

His Odes were to become the best received of all his poems in ancient times, acquiring a classic status that discouraged imitation: no other poet produced a comparable body of lyrics in the four centuries that followed[87] (though that might also be attributed to social causes, particularly the parasitism that Italy was sinking into).

[nb 19] The same motto, Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, had been adapted to the ethos of martyrdom in the lyrics of early Christian poets like Prudentius.

His influence on the Carolingian Renaissance can be found in the poems of Heiric of Auxerre[nb 27] and in some manuscripts marked with neumes, notations that may have been an aid to the memorization and discussion of his lyric meters.

[106] In France, Horace and Pindar were the poetic models for a group of vernacular authors called the Pléiade, including for example Pierre de Ronsard and Joachim du Bellay.

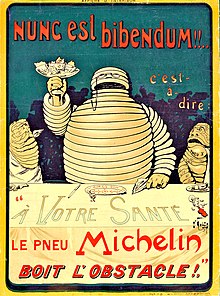

[nb 30] His verses offered a fund of mottoes, such as simplex munditiis (elegance in simplicity), splendide mendax (nobly untruthful), sapere aude (dare to know), nunc est bibendum (now is the time to drink), carpe diem (seize the day, perhaps the only one still in common use today).

[111] His works were also used to justify commonplace themes, such as patriotic obedience, as in James Parry's English lines from an Oxford University collection in 1736:[112] What friendly Muse will teach my Lays To emulate the Roman fire?

[nb 36] A. E. Housman considered Odes 4.7, in Archilochian couplets, the most beautiful poem of antiquity[127] and yet he generally shared Horace's penchant for quatrains, being readily adapted to his own elegiac and melancholy strain.

[128] The most famous poem of Ernest Dowson took its title and its heroine's name from a line of Odes 4.1, Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae, as well as its motif of nostalgia for a former flame.

Auden for example evoked the fragile world of the 1930s in terms echoing Odes 2.11.1–4, where Horace advises a friend not to let worries about frontier wars interfere with current pleasures.