Rail transport in Europe

The European Union (EU) aims to make cross-border operations easier as well as to introduce competition to national rail networks.

EU member states were empowered to separate the provision of transport services and the management of the infrastructure by the Single European Railway Directive 2012.

[citation needed] Across the EU, passenger rail transport saw a 50% increase between 2021 and 2022, with the 2022 passenger-kilometers figure being slightly under that of 2019 (i.e. before the COVID-19 pandemic).

[5] Switzerland is the European leader in kilometres traveled by rail per inhabitant and year, followed by Austria and France among EU countries.

Between Eastern European countries that use standard gauge and Belarus and Ukraine, the bogies of passenger trains are exchanged in a time consuming procedure.

[15] 15 kV AC has been used in Germany, Austria, Liechtenstein, Switzerland, Norway and Sweden since 1912, while the Netherlands and France use 1500 V DC.

France, Portugal, Lithuania, most of Southeastern Europe (Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania) and Turkey (also parts of the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Ukraine) use 25 kV AC, while Spain, Belgium, Wales, most of England, Poland, Italy, Slovenia, Moldova, the South Caucasus (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia) and Russia (also parts of the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Ukraine) use 3 kV DC.

All high-speed lines outside of Russia, including those built in Spain and Portugal, use 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge tracks.

ETCS is being developed as part of the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS) initiative, and is being tested by multiple railway companies since 1999.

[20] Similarly prior to the construction of High Speed 1 (then also known as the "Channel Tunnel Rail Link") to continental European standards, the first generation Eurostar trains were required to have several custom modifications compared to the TGV trains they are based on, including narrower loading gauge and provision for third rail electrification as used in southeast England.

The European Union Commission issued a TSI (Technical Specifications for Interoperability) that sets out standard platform heights for passenger steps on high-speed rail.

For example, in France the percentage is much lower than the European average, while it is much higher in other countries such as Lithuania, where over 70% of domestic cargo is transported by train.

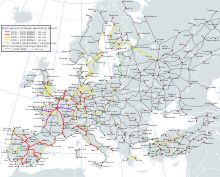

A big problem for long-distance international freight services – despite the European Single Market allowing freedom of movement of goods, capital, labor and people and the Schengen area drastically reducing internal border controls – is the variety of differing standards for electrification, loading gauge, signaling, driver certificates and even gauge.

While attempts to unify the divergent standards date back to at least the 1880s with the Conférence internationale pour l'unité technique des chemins de fer (lit.

Another problem is that unlike aviation, where Aviation English is a de facto global standard with few non-English holdouts, rail operations virtually always use the local language, requiring train operators either to be polyglots[36] or necessitating a change of staff at every (language) border.

While the Scharfenberg coupler, a mostly automatic system, is now commonly used on passenger trains,[37] its relatively low limit on the maximum tonnage it can pull makes it unsuitable for most freight operations.

[40][41] A pilot project regarding the digital automatic coupling system was launched by the German Federal Ministry of Transportation in 2020 and is to last until 2022.

[needs update][42][43] Train lengths in Europe are limited by the size of passing loops and refuge sidings as well as the placement of signals.

[44][45] There are plans to allow trains up to 740–750 m (2,430–2,460 ft) long to use the main freight lines by upgrading the requisite infrastructure;[46][47] various construction projects to that end have already been completed.

In addition, longer trains are considered to be more dangerous, as they provide more opportunities for freight cars to derail and make brake applications slower.

[1] Since the percentage of electrified railway lines varies between countries, freight operations may sometimes also be performed using diesel locomotives.

Train categories or types often have specific abbreviations, such as EC (EuroCity) or IC (InterCity), which are frequently also shown on passenger information systems.

Major metropolitan areas in most European countries are usually served by extensive commuter/suburban rail systems, including BG Voz in Belgrade (Serbia), the S-Bahn in Germany, Austria and German-speaking areas of Switzerland, Proastiakos in Greece, RER in France and Belgium, Servizio ferroviario suburbano in Italy, Cercanías and Rodalies (Catalonia) in Spain, CP Urban Services in Portugal, Esko in Prague and Ostrava (Czech Republic), HÉV in Budapest (Hungary), DART in Dublin (Ireland) and several more in the United Kingdom.

Increasingly the European Union mandates unified standards (see below) for newly built high speed lines to allow smoother international passenger services.

[citation needed] As of 2025[update], cross-border luxury trains in Europe include the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express, which runs between London and Venice, as well as national luxury train services in the United Kingdom (Northern Belle), Spain (Transcantábrico), Switzerland (GoldenPass Express) and Russia (Golden Eagle Trans-Siberian Express, which follows the Trans-Siberian Railway).

As of 2024[update], Spain operates the largest HSR network in Europe (3,966 km or 2,464 mi)[57] and the second-largest in the world after China.

The 2015 and 2017 performance reports found a strong relationship between cost efficiency and the share of subsidies allocated to infrastructure managers.

[7] The 2017 Index found Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland capture relatively high value for their money, while Luxembourg, Belgium, Latvia, Slovakia, Portugal, Romania, and Bulgaria underperform relative to the average ratio of performance to cost among European countries.

Virtually every European country with significant high speed rail ambitions developed its own, incompatible, standard, be it German LZB, French TVM or Italian BACC.